The idea for the Liverpool to Manchester railway was first suggested in 1822, as a faster and cheaper way of transporting goods from the textile mills in Manchester to the port of Liverpool.

In 1824 the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company was formed and George Stephenson was hired as the chief engineer.

However, the bill met with stiff opposition when first presented to Parliament and Stephenson was inadequately equipped for the cross examination so it wasn’t approved. A modified bill, this time with John Rennie as engineer, was passed in 1826, but Rennie demanded too high a salary, so Stephenson was re-appointed.

The construction of the Liverpool to Manchester railway presented many challenges for Stephenson. Not least of which was, what could be considered as his greatest achievement, the taking of the line over Chat Moss, a huge swamp just outside Manchester. He accomplished this by building a raft of heather and brushwood which the line floated upon. Stephenson also built the Edgehill Tunnel, which is 2240 yards long, the Sankey viaduct and the Olive Mount cutting which involved the removal of 480,000 cubic yards of red sandstone. There were also 63 bridges constructed, including the Skew Bridge at Rainhill.

The Liverpool to Manchester railway was opened in 1830, but before this could happen the company had to decide whether to use stationary engines and horses, or locomotives on the line.

So in 1829 the Rainhill Trials took place. The directors offered a prize of £500 for the best locomotive, and although there were originally 10 entries only 5 turned up on the day.

These were:-

Messrs Braithwaite and Ericsson of London with the ‘Novelty’ which weighed in at 2 tons, 15 cwt, 2 qtrs

Mr Brandeth from Liverpool with his entry the ‘Cycloped’ weighing 3 tons. This engine was pulled by two horses, on a drive belt.

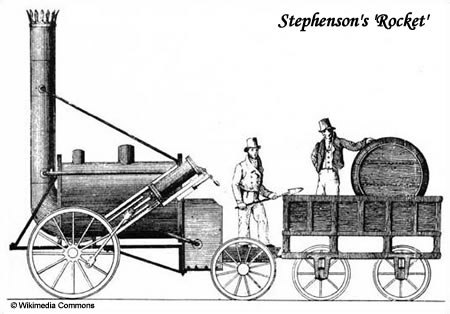

The ‘Rocket’, weight 4 tons, 3 cwt entered by Mr Robert Stephenson of Newcastle Upon Tyne.

Mr Burstall of Edinburgh with the ‘Perseverance’ which weighed 2 tons, 17cwt.

The ‘Sans Pareil’ weighing 4 tons, 8 cwt, 2 qtrs, was entered by Mr Timothy Hackworth of Darlington.

Spectators thought to be in their thousands arrived from Liverpool, St Helens, Warrington, Manchester and the surrounding countryside. The engines all had to achieve an average speed of 10mph and be able to pull three times their own weight forwards and backwards over the one and a half mile course, which started at Rainhill and finished at Lea Green.

After the first two days the conditions that the engines had to meet were modified. the main one being that they were expected to run 70 miles continuously.

‘Cycloped’ didn’t conform to the regulations and was disqualified. The ‘Perseverance’, which was damaged whilst being transported to the trials was finally able to compete on the sixth day, but could only reach about 6mph, so Burstall had to withdraw it. The ‘Sans Pareil’ reached a top speed of just over 16mph, but suffered a cracked cylinder.

The ‘Novelty’, which was a hot favourite with the crowd, reached speeds of 28mph, but the boiler pipe was damaged when it became overheated. Despite trying to repair it, Braithwaite and Ericsson were eventually forced to retire from the competition. The winner was the ‘Rocket’, proving to be the most efficient when it ran for 70 miles without mechanical failure, attaining a top speed of 27mph.

The railways went from strength to strength following the success of the Liverpool to Manchester line. The first inter-city line between London and Birmingham was opened in 1838, followed shortly afterwards by the linking of Birmingham to Liverpool by the Grand Junction, with London connected to Bristol, Southampton, Brighton and Dover by 1843. Between 1825 and 1829 there were just 51 miles of railway tracks in Britain, however by the mid to late 1840s this had increased to 3670 miles.

Dizzy Digital Cat

© Dizzy Digital Cat 2009

Sources

Mastering Economic and Social History by David Taylor 1988, The Macmillan Press Ltd