Until the 1700s, transportation in Britain relied either on the horse, on water, or indeed, a human being’s own feet.

However, with the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent mechanisation of production, there was a huge need for a transportation system, which not only supplied the raw materials and fuel to the factories, but provided a route for the finished goods to be distributed around the country, as well as to the rest of the world.

At the time the country’s roads were in a terrible state. If you wanted to travel around the country, you had to make the long and arduous journey by stagecoach, so called because the journey was made in stages with overnight stopping points at inns along the route. Very often these inns were run by wheelwrights, who would make the necessary repairs, while the passengers enjoyed their hospitality.

The stagecoaches were in competition with the Royal Mail coaches, which took passengers and were the fastest means of transportation at the time. Although if you were very rich you would travel in the privacy of your own coach, decorated on the side with the family crest.

The road was also a dangerous place to be, with the threat of highway robbery by the notorious highwayman, who would demand the passenger’s money and treasured possessions with the immortal phrases, “Stand and deliver!” and, “Your money or your life!” They operated on the main routes out of London in heath and woodland, but if caught, were sentenced to the gallows. When roads were turnpiked and gates and tolls introduced to pay for their upkeep, the highwayman’s getaway was thwarted. The last case of a highway robbery was reported in 1831.

Travelling by stagecoach was way out of the means of the humble agricultural labourer, whose only hope of horse-drawn transport was the local carrier. So it’s therefore not surprising that generation upon generation stayed within the same village or area. However the Industrial Revolution’s affect on the transportation system was going to change all that…

With the coming of industrialisation, a transportation network linking the coalfields, the supply chain and the distribution routes to the factories needed to be established. This could be by horse and cart, but this was only really practical for shorter distances. The country’s rivers (and coastal routes) were traditionally used as a means of transportation, and these waterways were made navigable, by straightening, clearing of obstructions and the construction of locks, all of which required the passing of legislation (with the inevitable local opposition) before work could begin.

Ironically, it was the industrial areas of Lancashire and the Midlands which were least served by the river network. The answer was to bring the rivers to them with the construction of man-made water channels, known as canals. One of the first of these new canals was the Sankey Brook Navigation which opened in 1757, linking the coalfields of Lancashire to the city of Liverpool and the River Mersey. It was originally intended to straighten the existing brook; however it proved much more practical to build a man-made cut running beside it.

The construction of more canals followed, particularly as the coal supplied through them undercut the opposition. The Bridgewater Canal, linking Runcorn, Leigh and Manchester was completed in 1761. This involved the construction of a viaduct over the River Irwell – the first of its kind.

The age of the canal had truly arrived, and the closing decades of the 18th century saw the canal network expanding, so that cities, industrial areas and ports were linked through a system of waterways, serving the demands of the new industrialised nation.

By 1830 the country had over 4000 miles of navigable waterways, and this together with the road network, provided the backbone of the inland transportation system. However both were soon to have stiff competition with the coming of the railways.

The Beginnings of the Railway

We have already seen in the February 2009 issue how James Watt’s development of the steam engine paved the way for the Industrial Revolution by powering the looms in the textile mills. However, his invention was to have an even greater impact in its use in railway locomotives.

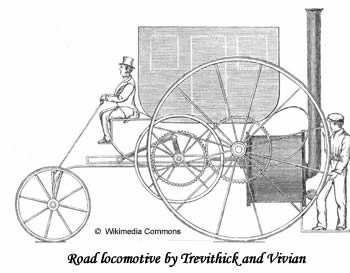

It was Richard Trevithick who built the first steam locomotive in 1800, although this was designed for the road and not rail use. Trackways (also known as plateways or tramways), originate from Roman times, although their use in this country in the context of the railways began in the 1700s. Initially, they were made of wood, although later of iron, and were used to transport coal from the pits to barges or sailing boats, with horses pulling the wagons.

The two were brought together in 1804 with Trevithick’s invention of the first steam-powered railway locomotive, which he successfully demonstrated on 21st February of that year, by pulling 5 wagons of 70 men and 10 tons of iron along the 9 3/4 mile Merthyr Tydfil tramway. The journey took 4 hours 5 minutes. Unfortunately, however, the weight of Trevithick’s locomotive broke some of the short-cast iron rails, so the railway continued to use horse pulled wagons, for which it was designed.

Richard Trevithick went on to build his ‘Catch Me Who Can’ locomotive in 1808, which he demonstrated to the public on a circular track in Bloomsbury, London. However, track weakness problems and public disinterest left him so disillusioned that he gave up designing railway locomotives, turning his attention to other projects instead. He died penniless in 1833.

Meanwhile others could see that his design had potential, and 4 years later, in 1812, the twin cylinder steam locomotive, ‘The Salamanca’, built by Matthew Murray, successfully replaced horses and wagons on the edged-railed Middleton Railway, which carried coal from the Middleton Colliery to Leeds in Yorkshire.

William Hedley had further success. He worked as an engineer at the Wylam Colliery in Northumberland, which had a horse-drawn trackway transporting the coal to the docks at Lemington-on-Tyne. He built ‘The Puffing Billy’ in 1813/1814, followed by the ‘Wylam Dilly’ in 1815.

It was during this time that father and son engineers, George and Robert Stephenson, were making a name for themselves, with George later to become referred to as ‘the father of railways’. George had been born in Wylam and his father had worked at the local pit where Hedley would later build his locomotives. In around 1811 he became the enginewright for the collieries at Killingworth, and it was here that he developed 16 locomotives for use on the tramway, including the Blücher built in 1814. However the problem of brittle rails still persisted and it was George Stephenson who improved the design of the cast iron rails, as well as finding ways to cushion the weight of the locomotives.

Legislation was passed in 1821 authorising the construction of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, which was to link several collieries in the Bishop Auckland area with the River Tees at Stockton. It was originally planned to be a horse-drawn plateway, however, boosted by his success at Killingworth, George Stephenson persuaded the founder, Edward Pease, that the use of locomotives would be a vast improvement. George and his son Robert joined in partnership with Pease, together with Michael Longridge of the Bedlington Ironworks, which provided the wrought iron track, which was strong enough to support the locomotives.

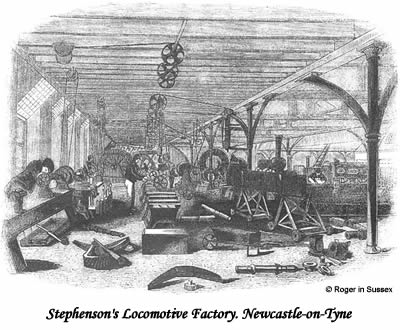

A works was built in Forth Street, Newcastle, producing the locomotives for the new line. The first to be completed was the ‘Locomotion’, which was completed in September 1825. It was this, driven by Stephenson, hauling an 80 ton load of coal and flour, as well as a purpose built passenger car occupied by dignitaries along 9 miles of track, which opened the railway on 27th September 1825.

It was not entirely successfully as horse power and stationary engines were used on parts of the track for another 8 years. However, it was to be a very significant day in the history of the railways, as not only was it the first time that passengers had been transported on a steam locomotion railway, but also that the gauge Stephenson used for the track – 4ft 8 1/2 inches – was to be later adopted as the standard throughout Britain and the rest of the world.

His next major accomplishment was his work on the Liverpool to Manchester Railway which opened in 1830, which you can read about in Dizzy Digital Cat’s article about the Rainhill Trials in this issue.

Boom times to Beeching

The viability of rail transport was now proven, and railway companies were being established all over Britain, planning their new railway lines, raising money to finance them and seeking parliamentary permission to build them. The Government had a rather blasé attitude towards granting permission, and lines were built with the railway companies’ commercial interests very much at heart, with no thought given to the creation of an efficient railway network for the future. Very often lines were duplicated in some areas, whilst others had no service at all. Also, many of these projects were ill-conceived and financially unsound. The whole system needed a central body who would oversee the creation and running of this new infrastructure. The Regulation of Railways Acts 1840 and 1844 gave the government this role, through the Board of Trade.

Driven by profit, many railway companies had no interest in transporting the poorer classes, and those who did provide third class travel did so in wagons open to the elements and the smoke from the locomotive. The act of 1844 required that each company provide at least one cheap train per day, with covered carriages, at a cost of no more than one penny a mile, thus making train travel a possibility for all classes of society.

Further acts of parliament were passed to counter the monopoly of the railway companies, after a series of accidents, and as they continued to take dominance of the country’s transportation system, such as The Regulation of Railways Act of 1873 and the Railway and Canal Traffic Act of 1888. By 1845 over 2000 miles of track had been laid down, linking cities and towns all over the country, with incredible feats of engineering to meet the constant challenge of the country’s terrain.

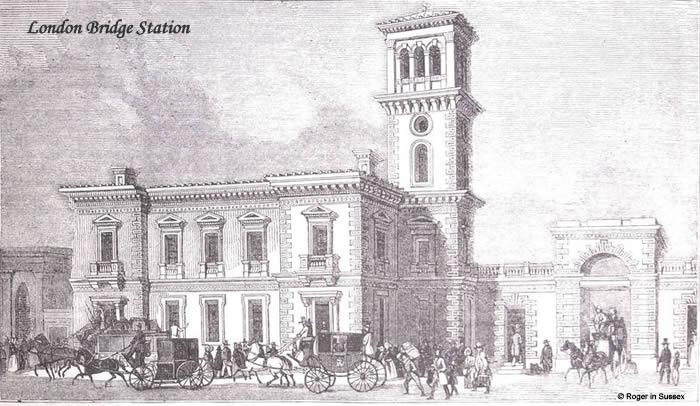

The first London station was London Bridge which was opened in 1836. This illustration of the original station (rebuilt in the 1850s) appeared in the Penny Magazine on 30th December 1843, together with the following report:-

“Of the Brighton, Croydon, and Dover Joint Railway terminus at London Bridge, the extensive works have been carried on with such diligence as to be now approaching towards completion. The area occupied by them, exclusive of the original Greenwich station, to which they adjoin on the south, comprises nearly three acres. The iron roofs covering the whole of the space appropriated for the arrival and departure of passengers and carriages extend over a surface of more than an acre and a quarter, and exhibit a combination of superior scientific skill and correct taste, highly creditable to both the engineer and the architect, Mr. H. Roberts, employed upon them.

What, however, most attracts notice, is the general architectural façade of the Terminus, which, though of but moderate height in itself, is rendered conspicuous both by its situation and by the campanile tower, which, besides being a marked object in itself, contrasts forcibly and favourably with the lower horizontal mass. Our view exhibits only the portion now executed, viz. the south wing of the principal building, with the campanile and the large archway forming the entrance for private carriages to be conveyed by the trains. This line of front will consist of five compartments, three of three windows each in breadth, and a smaller one at each end only a single window in breadth. Accordingly, the view shows one-half exclusive of the centre window, or five windows out of eleven on the upper floor, and one of three doors of the centre compartment – the only circumstance which distinguishes that division of the façade. The ground floor of the centre building is appropriated to the general booking-offices; and the upper one, which is approached by a stone staircase in the tower, to rooms (including an elegant and spacious one in the rear), chiefly for the half-yearly meetings of the three companies”

London Bridge was followed by Euston (1837), Paddington (1838), Bishopsgate (1840), Waterloo (1848) and King’s Cross (1852), all of which were the terminus of various railway company’s lines from around the country. However, if travellers wanted to continue their journeys through another station they had to rely on horse drawn transport on the congested London streets.

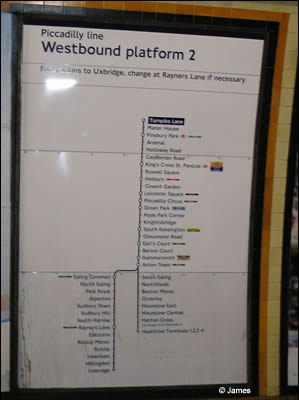

In 1854 an act of parliament was passed approving the construction of a subterranean railway below London, initially to link Paddington Station with Farringdon Street and King’s Cross, and was to be known as the Metropolitan Railway. This underground railway was finally opened in January 1863, and was soon expanding to Hammersmith and Moorgate Street, Kensington and Swiss Cottage. As these lines reached into the countryside around London, these areas soon become the suburbs of the metropolis, and the commuter was born.

The arrival of the railway to the small fishing village of Brighthelmston on the Sussex coast in 1841 was the catalyst which would transform it into the fashionable seaside resort of Brighton, attracting thousands of day trippers a year.

This was the golden age of the railways, with cities, towns and villages linked through an intricate web of railway lines stretching right across the country. No longer was the poor agricultural labourer ‘trapped’ in his small village, like his ancestors before him. The growing cities needed workers who flowed in through the railway network. Most ended up living in the slums, whilst those of means moved out to the suburbs.

In the closing decades of the 19th century, the number of railway companies had been drastically reduced by a series of amalgamations and take-overs, so that one company would control a region of the country instead of a local area. These huge monopolies began to cause concern and with calls for a nationalisation of the railways, the government sought to take more control, which they did during the First World War, when the railways were used to transport thousands of troops, as well as equipment and artillery.

The Government’s control continued until 1921, however they wanted the benefits of this to continue, although they didn’t go as far as nationalisation. The Railways Act of 1921 came into force on 1st January 1923 and grouped the vast majority of companies into the ‘Big Four’ – the Great Western Railway, London and North Eastern Railway, the London Midland and Scottish Railway, and the Southern Railway.

However, by now the railway was competing with the motor car, buses and road haulage, so by the time of the Second World War, when again the Government took control, the companies were virtually bankrupt, with the infrastructure suffering from years of under-investment.

The Transport Act of 1947 nationalised the railways (including the London Underground) and they became known as ‘British Railways’ (later British Rail or ‘BR’), under the control of the British Transport Commission. The act also nationalised road haulage, and for the next 6 years until it was returned to private ownership, passenger numbers on the railways increased, the system was profitable, and some of the tracks and stations were updated, with diesel and electrification starting to be introduced. However, with road haulage back in private hands, British Rail faced stiff competition for freight handling, so again started to make losses, even though cuts were being made by the closure of little used lines and stations. Something had to be done to make BR more profitable, and this is when they called in Dr Beeching.

Dr Richard Beeching, on placement from ICI, was given the unenviable task of reorganising the British Rail network to make it profitable. He published his report ‘The Reshaping of British Railways’ on 27th March 1963, which called for the closure of over 2000 railway stations and the pulling up of around 5000 miles of track, which, he believed would make a net saving of around £18 million a year. Not surprisingly there was a public uproar, so when he published his second report in 1965, calling for even more cuts, reducing the railway system into a ‘skeleton’ network, he was forced to leave his post by ‘mutual consent’.

Even so, many of his recommendations were implemented, and the following decade saw the closure of many branch lines, with stations demolished or turned into residential use, the tracks removed, and the remaining steam locomotives taken out of service. The system became more cost effective, and after the disastrous re-privatisation in the 1990s, is now back in state hands with the train operators run as franchises.

It’s ironic now when we’re faced with traffic congestion, pollution and global warming that we’re looking again at the railways, in particular the closed branch lines, as a means of transportation. Some of these were reopened in part by railway enthusiasts, where they would relive the days of steam. The Bluebell Railway in Sussex has gone further and has recently reopened its link with East Grinstead closed over 50 years ago, although it will still be some time before it takes passenger services.

The coming of the railway thoroughly changed the working lives of our ancestors. After generations of working as labourers, they suddenly had an opportunity to widen their horizons, leaving behind their traditional way of life.

My 3x grandfather, Henry Guilford, was born in the small fishing village of Brighthelmston (now Brighton) on the Sussex coast in 1817, and was the son of a fisherman, like generations before him. The coming of the railway in 1841, totally changed Henry’s prospects, as he took a job working as a railway policeman, then as a guard, eventually rising to a station master, until his untimely death from Phthisis in November 1862. All of his sons followed him into the railway, working as engine fitters, wagon builders and blacksmiths, with one ascending to the position of station master, like his father before him.

By 1849, Henry was one of almost 60,000 workers on the British railways. This was a whole new working world for them, as the railway companies were developing their networks and writing the ‘rule book’ as they went. However, even in these early days, safety and punctuality were paramount, so discipline was essential, with fines from workers’ pay for driving the engines too fast, causing collisions, passing dangers signs, allowing friends and family members to ride on the footplate etc. Railwaymen were expected to be upstanding members of the community and have pride in themselves and their work.

As the railways developed from the trackways at the collieries, many of the early drivers and fireman were recruited from these for their experience with locomotives. Although for many, they had to learn as they went on. Their hours were long and their work dangerous however their wages were much more then they would have expected working as labourers and this, together with tied properties, no doubt added to the lure. Provided they kept to the rules then it was a job for life (as well as for their off-spring), with excellent prospects for the more literate, numerate and ambitious, as they moved up each rung of the career ladder.

By the 1890s railwaymen enjoyed benefits of their employment previously unheard of, such as an annual holiday, health care through a benefit society, savings schemes, as well as a host of leisure activities and cheap railway travel for their families.

Drivers would start off as engine cleaners and once they had acquired the necessary skills were given the additional responsibility of firing the locomotives. They then progressed to a full-time firemen, and then a ‘passed’ fireman who was deemed capable of taking over the controls from the driver on an occasional basis. On promotion to engine driver they would initially be given shunting jobs and sent on short journeys. When they were eventually in charge of the huge fast locomotives on the long distance runs they were usually in their 50s and had years of experience to be able to handle them safely.

When Henry Guilford worked as a guard on the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway one of his responsibilities would have been to manually operate the train’s brakes in the brake van. This practice continued until the late 1870s, when a more efficient braking system was introduced, drastically reducing the number of crashes and collisions.

Henry became a station master at the newly opened station at Henfield, Sussex, just a few months before his death, after serving 21 years as a guard. Station staff such as telegraph clerks, porters and ticket clerks had similar prospects. The station would often be the station master’s family home, where he would be on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. It was a prestigious and well paid job, and he would have been a well-respected member of the community.

In larger stations, with many more staff to administer, many of the station master’s daily responsibilities were taken on by a foreman, although he was still in overall authority. The railway served as the line of communication between the station and the management at head office, bringing paperwork on a daily basis, although more urgent messages were sent by telegraph.

Each member of the station staff had their own responsibilities, whether it be the ticket clerks ensuring that they had an adequate supply of tickets, or the porters that they didn’t mislay any packages or parcels in their charge. The railway was expected to run like clockwork, with the station kept spic-and-span, and if a particular member of staff was slacking in their duties then they would have expected to be reprimanded. Periodical visits by the inspectors would also ensure that the station was being run ‘by the book’.

The porter or the telegraph boy at the rural stations may have had aspirations to become a signalman, who would operate the signals and change the points from his box, and would help out when required to gain the necessary experience. To be a signalman at the large city stations with their complex array of points and signals required special training to cope with this very demanding job.

Long before automation, each railway crossing had to be manned, ensuring that the gates were opened and closed for the smooth running of the railway. Each came with a small tied cottage and the job was usually given to older employees.

The maintenance of the track was the responsibility of the platelayers who would work in gangs headed by a ganger, ‘walking the line’ on a daily basis checking for damage and making the necessary repairs. They would also cut back trees and undergrowth at the side of the line as a spark from the engine could cause a fire. They had to be ever watchful for oncoming trains, whatever the weather and the level of visibility, so needless to say it was a very dangerous job.

When the Guilford family returned to Brighton after Henry’s death, his sons Charles (my 2x great grandfather) and Edward worked at the locomotive works which ran alongside Brighton station. Their older brother Henry had already moved north to Gorton in Manchester, where he worked as an engine fitter. These were just two of the huge works around the country which built and repaired locomotives and rolling stock, employing thousands of workers who toiled long hours in hot, fumy and dangerous conditions.

In this male dominated profession, woman were finally allowed to work on the railways during the First World War to replace railwayman who had enlisted to fight at the front. The year after Armistice saw the number of railway workers reach its peak of around 750,000. However, as the railways started to lose money and with the closure of branch lines and stations post-nationalisation and Dr Beeching, numbers were drastically reduced, together with the pride and prestige of the job.

I was immensely proud to discover my very own ‘railway family’ who each played their own part in a railway system, just the shadow of which can be seen today.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2009

Sources

Transport in Britain 1750-2000 From Canal Lock to Gridlock ~ Philip Bagwell and Peter Lyth

Railway Records – A guide to sources ~ Cliff Edwards

Further Reading

Turnpike roads and tollhouses in England

The Canals of England and Wales and their History

Bluebell Railway – A Steam Railway in Sussex, UK

Tracing Railway Ancestors

If the record of your railwayman still exists then it will be held at the National Archives in Kew. See their catalogue for more information. Railways: Staff Records.

Railway Records – A guide to sources~ Cliff Edwards

The Railwayman ~ RS Joby