In 1989 my cousin died. Following the reading of his will, I was sent a list of his personal effects from which to choose two items. To be honest, there was nothing that I really wanted; the list consisted mainly of clothing, crockery, cutlery, a few small pieces of furniture and other general household effects.

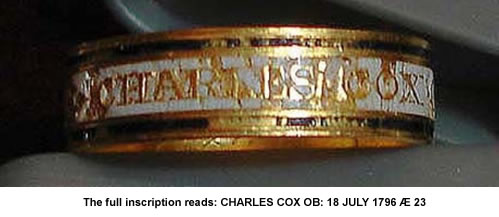

There were very few personal items at all. Eventually, I selected his late mother’s riding stirrups, as I had many photographs of her on horseback. But what should be my second choice? I noticed an item at the end of the list – ‘mourning ring’. Having no real idea of what a mourning ring was, I put this down as my second selection and sent the list back to the solicitors.

A few weeks later a small package arrived in the post. Inside was a pair of stirrups. Not the shiny metal and glossy leather I had imagined, but decidedly scruffy and broken, so they were consigned to the back of a cupboard. Also in the parcel was an envelope containing the mourning ring. This was bashed and battered, and far too big for any of my fingers; I should have put it with my other jewellery, but feeling fed up, I shoved it in a drawer and forgot all about it.

Not long after this, I became interested in family history. Of course, I didn’t think of looking at the mourning ring and so was initially unaware of the story it could tell.

Charles Cox was born in rural Dorset in 1773. He was the eldest son of my 4x great grandparents, Charles Cox and Dorothy, née Crane, and was baptised at the parish church of St Nicholas in Child Okeford on 25th July 1773. Charles’ parents probably hoped that he would become a wheelwright like his father, or perhaps have the chance to be a yeoman farmer as many of his maternal relatives had.

Possibly Charles had other ideas! Not far from Child Okeford on the edge of the Blackmore Vale are Bulbarrow and Okeford Hill. Bulbarrow is the second highest point in Dorset, and there are spectacular views across Dorset and through to Somerset and Wiltshire. Maybe these views gave Charles the wanderlust?

He may have done some work with his father, as he became a carpenter, but instead of staying in the village of his birth, he joined the Royal Navy.

I don’t know a great deal about Charles’ life in the navy, but do know that his career was cut cruelly short. By 1796 he was working as a carpenter’s mate on board His Majesty’s Ship ‘Crescent’.

‘Crescent’ was a 36-gun, fifth rate, square rigged frigate and had been launched in 1784. In July 1796 the ship was at anchor in Simon’s Bay at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, whilst some minor repairs and maintenance took place.

On the morning of Monday 18th July 1796, Charles was working in the ship’s rigging doing some painting.

The ship’s log for that day states: “Employed painting in rig, departed this life Charles Cox carpenter’s mate, by occasion of a shot fired from the shore”

On 23rd July, a court martial assembled on board His Majesty’s Ship ‘Ruby’ in Simon’s Bay. Present were six ship’s captains and their commodore, John Blankett, who presided over the court. These men had gathered to try Mr Edward Nixon, surgeon’s second mate of His Majesty’s Ship ‘Sceptre’.

They heard evidence that Edward Nixon had been shooting at seabirds from his position onshore and had inadvertently aimed towards the rigging of ‘H.M.S. Crescent’, where Charles Cox had been working. The dead man had been killed instantly.

The court record concludes:

“Having heard the evidence and what the prisoner had to alledge [sic] in his defence, and having maturely and deliberately weighed and considered the whole, the court acquit him of any criminal intent and he is hereby honourably acquitted accordingly.”

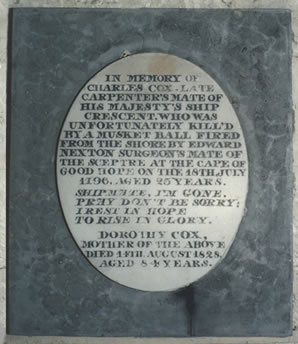

So, Charles Cox might have been forgotten forever, that is, except for the fact that his family wouldn’t allow it! The first time I visited the church in Child Okeford I saw a plaque on the interior wall of the church tower and realised it referred to my relatives.

Even then I didn’t think of the mourning ring, but a short while later I had a burglary at my home. Amongst other things, my jewellery box was taken. I had to make an inventory of the contents and in order to be certain of what to include, I did a search of the drawers in my bedroom. Of course, the only thing that had been missed by the burglars was the mourning ring, as it hadn’t seemed important enough to warrant a place with my jewellery!

When I think how easily this bit of family history could have been lost forever; firstly it must have passed through a convoluted route to get to my great-aunt in the first place, secondly, I might not have chosen the ring from the inventory and it would therefore have probably been sold, and thirdly because it should, by rights, have been stolen in the burglary, really it’s a miracle I have it at all!

Sometimes I wonder if something, or someone, guided my actions and the actions of those who came before me?

Merry Monty Montgomery

© Merry Monty Montgomery 2008