When the ocean liner ‘Titanic’ hit an iceberg at 11.40pm on 14th April 1912 and sank in the early hours of the following morning, with the loss of around 1500 lives, it was one of the worst peacetime maritime disasters in history, and was the catalyst for the improvement of safety standards at sea, as well as changing maritime law.

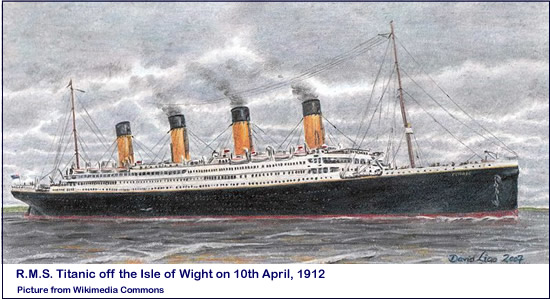

The three Olympic class liners of the White Star Line, the ‘Olympic’, the ‘Titanic’ and the ‘Gigantic’ (later renamed the ‘Britannic’), were first envisaged in 1907 to compete with the luxury liners of the Cunard Line. Work on the ‘Olympic’ had started at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast in December 1908, with work on the ‘Titanic’ starting the following March. The ‘Titanic’ was launched from its giant gantry in May 1911, seven months after the ‘Olympic’ and the outfitting began. However, in September 1911, the ‘Olympic’ collided with ‘HMS Hawke’ off the coast of the Isle of Wight and had to come back to Belfast for repairs. Work on the ‘Titanic’ was therefore delayed, and the date of the maiden voyage, originally 20th March, was put back to 10th April 1912.

The ‘Titanic’, together with its sister ship the ‘Olympic’, were the largest and most luxurious ships of their time, with the former having the capacity for 3547 passengers and crew. The passengers travelled in either first, second or third class, with each having its own areas and facilities. Of course, the first class areas were the most opulent, with finely decorated common rooms, staterooms, parlour suites, restaurants, verandas and promenades. The ship boasted libraries, a gymnasium, a Turkish bath, a swimming pool and even a squash court.

The ship had the most up-to-date technology, with the latest navigational equipment, and two Marconi radio sets providing constant contact with the outside world.

Steam powered generators provided the ship with an extensive electricity system, which powered the ship’s lights. Its double-bottom hull with its 16 watertight compartments which could be sealed from the bridge, led the press to describe the ship as ‘practically unsinkable’.

The Commodore of the White Star Line and captain of the ‘Titanic’, Captain Edward John Smith, did little to dispel this myth, and is reported as saying, “I cannot imagine, in our age, such a grand ocean liner as the Titanic foundering. The newspapers seem to be correct in their statements”. It is therefore not surprising that many people actually believed this to be the case.

Even so, the ‘Titanic’ had just 20 lifeboats, which could only accommodate up to 1178 people, but this still exceeded the legal requirements of the time. It was thought that on the busy shipping lanes of the North Atlantic they would only need to be used to ferry passengers to a rescue ship, in the unlikely event of an accident.

There could, however, have been more lifeboats, but the White Star Line’s Managing Director, J Bruce Ismay, rejected these plans as he felt that they took up too much deck space.

Sea trials took place in the Irish Sea on 2nd April 1912, with Captain Smith in command. All went well and the ship was passed as satisfactory by the Board of Trade.

A national coal strike, which had begun in January 1912, was still ongoing in the April. So coal was diverted from the company’s other ships to the ‘Titanic’ in order that the maiden voyage was not delayed any further. Many passengers had actually booked to sail on other ships, but had their plans changed when there wasn’t the coal available for them to sail. Other passengers, particularly those in third class, had booked tickets for the next available sailing, and for these ‘lucky’ people this was to be the ‘Titanic’.

The ‘Titanic’ arrived in Southampton on the night of 3rd April 1912, and the following days were spent loading provisions, supplies and cargo, as well as hiring the crew.

With all the passengers and their luggage aboard, the ‘Titanic’ left the dockside at Southampton around lunchtime on 10th April 1912.

Captain Smith was in command, supported by his officers; Henry T Wilde, William Murdoch, Charles Lightoller, Herbert Pitman, Joseph Boxhall, Harold Lowe, James Moody and Herbert McElroy.

However, they were not to leave without incident. As the ‘Titanic’ passed the passenger ship, ‘New York’, it broke away from its moorings and narrowly missed hitting them by just a few feet. A portent of events to come perhaps?

By early evening they had arrived in Cherbourg, Northern France, where most of the first class passengers joined the ship. The following morning they arrived in Queenstown (now Cobh), Southern Ireland, where most of the third class (or steerage) passengers boarded. By the early afternoon they had set sail on their voyage across the North Atlantic ocean, expecting to arrive in New York on 17th April.

The total of passengers and crew onboard was 2207. This was made up of 324 first Class, 277 second Class and 708 third class passengers, together with 898 crew members, some of whom were not directly employed by the White Star Line.

The ‘Titanic’ has been described as a microcosm of society at the time.

The first class passengers not only included the White Star Line’s Managing Director, J Bruce Ismay, and the ship’s designer Thomas Andrews, but some of the richest and most important people of the day, including John Jacob Astor IV, Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and other prominent figures in 1912 British and American society.

Those travelling second class were those with a moderate income but without the social status to travel first class, such as merchants and professionals.

The third class passengers were mainly immigrants of various nationalities, escaping the poverty of their homelands and planning a new life in America. They were commonly referred to as ‘steerage’, because traditionally they were housed with the steerage equipment onboard ship. Their accommodation onboard the ‘Titanic’ was comparatively luxurious.

The journey had been pretty much uneventful as the passengers enjoyed the facilities onboard. For reasons unknown, Captain Smith decided that the usual Sunday morning lifeboat drill was not necessary.

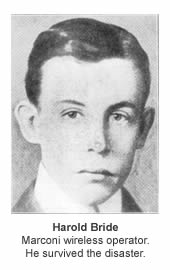

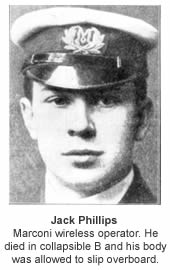

However, in the radio room, messages were being received from other ships in the area by the Marconi wireless operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, advising that “bergs, growlers and field-ice” had been spotted on their intended course.

Most, but not all, of these reports reached the captain and his officers on the bridge. Both Phillips and Bride were working flat out to clear the backlog of passengers’ personal messages, caused by an earlier equipment failure.

At 11.40 pm on the night of Sunday 14th April 1912, conditions on the North Atlantic ocean were still, clear and bitterly cold. Up in the crow’s nest the lookouts suddenly spotted an iceberg directly ahead, which looked like a black mass surrounded by a white mist and was therefore difficult to see unless close by. They immediately sounded the warning bell and telephoned the bridge with the announcement “iceberg right ahead!”. The officers on the bridge issued the orders for “hard-a-starboard” and for the engines to be stopped and reversed, as well as closing the watertight doors. Despite their efforts the ‘Titanic’ struck the iceberg on its starboard bow side and the first five, of the liner’s sixteen watertight compartments began to fill with seawater.

At first, as Captain Smith, his officers and Thomas Andrews, together with J Bruce Ismay assessed the damage and discussed the appropriate action required, it seemed inconceivable to them, and to everyone else on board, that the unsinkable ‘Titanic’ was actually going to sink. As the ship continued to take on more water, they soon realised that it was doomed.

The Marconi wireless operators were instructed to signal for help using the traditional CQD (come quick, danger). They also used the relatively new signal SOS. The Cunard liner, the ‘Carpathia’, which was 58 miles away, was the first to respond and rushed at full speed to their assistance.

As the officers fired distress rockets into the night sky, the Leyland Line steamship, the ‘Californian’, lay in field ice just 20 miles away. Both the radio operator and the captain, Stanley Lord, had retired for the night, and the crew on duty chose to ignore the distress rockets, to much later condemnation.

Captain Smith ordered the steam in the boilers to be vented through the funnels to prevent them from exploding when coming into contact with the sea water, which caused a tremendous noise, hindering communication and creating confusion and misunderstanding.

Those passengers and crew not awoken by the collision, and the resulting commotion and noise, were roused from their sleep and told to put on warm clothing and their life jackets, and to go up on the bitterly cold deck. Language difficulties, particularly amongst the third class passengers, caused further confusion and misunderstanding, with many not understanding the situation and what they were expected to do.

Once all the steam was released through the funnels, the ship’s orchestra began playing to entertain the passengers.

Almost an hour after the collision, the covers were taken off the lifeboats and they were prepared to be launched. Captain Smith gave the order for “women and children first”. Second Officer Charles Lightoller was in charge of the boats on the port side and First Officer William Murdoch on the starboard side. Lightoller followed the rule to the letter and would not let any man board the lifeboats, however Murdoch was less strict and permitted men if no women were ready to board. The only other men allowed on board the lifeboats were the members of the crew who were needed to man them.

Many women left their husbands, sons, fathers and brothers onboard the ‘Titanic’ that fateful night, never to see them again. Although some, such as Ida Strauss, chose to stay with her husband, Isidor, owner of the New York department store Macy’s. They both died in the disaster.

Even so, all of these lifeboats were launched well below capacity, as many people still believed that they were far safer staying onboard the ‘Titanic’. It was much later, when the fate of the liner became increasingly obvious, that the last of the lifeboats were filled above maximum capacity, with the crew having to form a human chain, and shots having to be fired into the air to continue to enforce the captain’s order of ‘woman and children first’.

With many women and children still on board and with the men expected to stand back and accept the inevitable, J Bruce Ismay, Managing Director of the White Star Line and the man who had rejected the plans to include more lifeboats, stepped calmly on board one of the last remaining collapsibles. This was perceived by the British and American press as an act of sheer cowardice, for which he received much criticism and disgrace.

At around 2.20am, with the ship’s bow starting to sink under the water and the decks getting gradually steeper, Captain Smith gave the order, “every man for himself”. The band stopped playing, the Marconi wireless operators left their positions and, as the bow plunged under the surface, many passengers and crew jumped overboard.

Some made their way to the last two remaining collapsible lifeboats, A and B, which had come adrift as the deck hit the water. The latter of the two was upside down and soon become seriously overloaded, with many people turned away. Those who made it aboard were soaked through and huddled together to keep warm. Several died during the night, including the Marconi wireless operator Jack Phillips. Their bodies were allowed to slip over the side.

Suddenly, there was a huge roar as all of the moveable objects on board the ship shifted towards the submerged bow. The lights, which the engineers deep within the ship were still working hard to maintain, blinked once and then went out. The ship, now in darkness, broke in half and the forward funnel collapsed, crushing several people including John Jacob Astor IV.

The stern section was left afloat for a short while and settled back down onto the surface, but as it started to fill with water it gradually pointed up in the air, with the ship’s three huge propellers raised high above the water, and then sank, leaving the remaining passengers afloat on the ocean. They thrashed around in the freezing cold water screaming for help, but within 20 minutes they had all perished.

After the sinking, Fifth Officer Harold Lowe reorganised the lifeboats to increase the capacity but, by the time he had gone back for the survivors in the overloaded collapsibles, he found very few still alive afloat in the water. Lowe’s lifeboat was the only one to go back, as the rest feared that they would be overwhelmed.

There were many acts of bravery and selflessness that night. First class passenger Margaret ‘Molly’ Brown, the wife of a Denver gold prospector and herself an activist in woman’s rights, was helping the woman board the lifeboats, when she was forcibly put into lifeboat 6.

Quartermaster Robert Hitchens had been put in charge and as the lifeboat had been launched half-full, she openly challenged his decision not to go back for survivors, but was overruled by the others on board as they feared that they would be swamped. Margaret rowed lifeboat 6 that night, something Hitchens was not prepared to do. So when he tried to prevent them from wrapping up a freezing cold stoker, who had been transferred onto their boat, she threatened to throw the quartermaster overboard.

When the ‘Carpathia’ finally arrived almost two hours later, the area was strewn with floating debris and bodies, which were still being recovered several weeks later. Although only a small proportion of those lost were found, and many could not be identified.

Of the original 2207 passengers and crew, only 712 survived. This was made up of 201 first class, 118 second class and 181 third class passengers, as well as 212 crew.

Around 1500 people lost their lives that night, including Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews, officers William Murdoch, Henry T Wilde and James Moody. All of the engineers, who had worked so hard to maintain the lights until the ship broke apart, lost their lives, as well as the members of the ship’s orchestra who had played right to the end.

When the ‘Carpathia’ arrived in New York on 18th April 1912, carrying the shocked and dazed survivors, questions were already being asked why the disaster had happened and who was to blame.

The subsequent American and British inquiries resulted in many improvements to safety at sea, including ships having to reduce their speed when expecting icebergs and having to have enough lifeboats on board for all of the passengers and crew. The International Ice Patrol, which monitors icebergs in the North Atlantic ocean, was set up in 1914 as a direct result of the disaster.

The ‘Titanic’ lay undiscovered on the ocean floor, south east of Newfoundland, for 73 years. It was finally found by an expedition led by the oceanographers Robert Ballard and Jean-Louis Michel on 1st September 1985. Since then many artifacts have been recovered, including a 17-ton section of the hull, and some of these are now on show to the public in museums and exhibitions.

However, it is the visits by salvagers and tourists which are hastening the deterioration of the wreck and it is thought that the structure will collapse onto the ocean floor within the next 50 years.

Millvena Dean, is the last of the ‘Titanic’ survivors. She was just two months old at the time and lost her father in the sinking. Despite her age she is still very much involved in ‘Titanic’ related events and has been invited to speak at an event in Southampton this month to commemorate the 96th anniversary of the disaster.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2008