Almost the first family I tried to research after getting hooked by genealogy was my grandmother’s mother’s family – the Sephtons. My father had many memories of their narrow boat building yard at Hawkesbury Junction, and my brother, who actually lives on a narrow boat, discovered an article about the family and their businesses in Warwickshire which fired my imagination.

I was lucky enough to find a contact on Genes Reunited who was in possession of a genealogical chart going back to Eduardi Sephton – born in 1633 in Misterton near Gainsborough. By 1798, his 2x great grandson Francis Sephton (born in West Stockwith in 1759) and his extended family, from two previous wives, had moved to Shardlow in Derbyshire. He was working as a boatbuilder, a trade followed by his sons, two of whom stayed in Shardlow, and the other (my 4x great-grandfather James) moved to Foleshill and with his son John, founded the Sephton’s boatbuilding yards at Tusses Bridge.

Meanwhile, James’ brother Hezekiah who was a carpenter (born in West Stockwith on 9th March 1776) had a very different future ahead of him. In 1820 the British Government sponsored a scheme whereby 4,000 British were settled in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, and Hezekiah, a carpenter of 1 Bedford Court, New North Street, Red Lion Square, London, led one of the three largest parties – 344 Methodists from London aboard the ships ‘Aurora’ and ‘Brilliant’. Each family paid a deposit of £10.00 which was repaid after three months in South Africa, and each family was settled on 100 acres which became theirs after a few years.

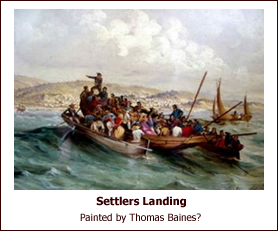

There were numerous delays, not least the freezing of the Thames. The ships ‘Aurora’ and ‘Brilliant’ were to carry Sephton’s party, made up of Wesleyan tradesmen and their families, but were stuck in the ice until they were finally able to sail from Gravesend on the 15th February 1820 bound for Salem on the Assegai Bush River. They made landfall at Simon’s Bay on 1st May and landed in Algoa Bay, Port Elizabeth exactly three months after leaving England. The party are reported to have landed singing the hymn ‘Come Thee that Love the Lord’.

The journey had not been without incident: Two emigrants died on board the ‘Aurora’ before she sailed. The Rev William Shaw’s journal records that Elizabeth Jones, the 21-year-old wife of John Jones, died at sea, and ‘several children were born and some died’. One of these was Hezekiah and Jane’s son William Sephton who was born ‘at sea aboard Aurora bound for S. Africa’.

‘Brilliant’ was a day ahead of ‘Aurora’, and the two parties were reunited at Algoa Bay. Thomas Pringle, the leader of the Scottish party on board the ‘Brilliant’ wrote about the journey from Simonstown to Algoa Bay:

“We sailed out of Simon’s Bay on the 10th May with a brisk gale from the N.W., which carried us round Cape L’Aguillas, at the rate of nearly ten knots an hour. On the 12th, at day-break, however, we found ourselves almost becalmed, opposite the entrance to Knysna, a fine lagoon, or salt-water lake, which forms a beautiful and spacious haven, though unfortunately of rather difficult access, winding up, as we were informed by our captain. During this and the two following days, have scarcely any wind, and the little we had being adverse, we kept tacking off and on within a few miles of the shore. This gave us excellent opportunity of surveying the coast scenery of Auteniqualand and Zitzikama, which is of a very striking character.

We at length doubled Cape Recife on the 15th, and in the late afternoon came to an anchor in Algoa Bay, in the midst of a little fleet of vessels, which had just landed, or were engaged in landing, their respective bands of settlers. Around us in the west corner of the spacious bay, were anchored ten or twelve large vessels, which had recently arrived with emigrants, of whom a great proportion was still on board.

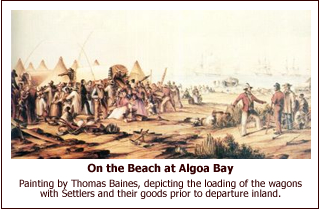

Directly in front, on a rising ground a few hundred yards from the beach, stood the little fortified barrack or blockhouse, called Fort Frederick, occupied by a division of the 72nd regiment, with the tents and marquees of the officers pitched on the heights around it. At the foot of these heights, nearer the beach, stood three thatched cottages and one or two wooden houses brought out from England, which now formed the offices of the commissaries and other civil functionaries appointed to transact the business of emigration, and to provide the settlers with provisions and other stores, and with carriages (ox-wagons; U. T.) for their conveyance up the country. Interspersed among these offices, and among the pavilions of the functionaries and naval officers employed on shore, were scattered large depots of agricultural implements, carpenters’ and blacksmith’s tools, and iron ware of all descriptions, sent out by the home government to be furnished to the settlers at prime cost. About two furlongs to the eastward, on a level spot between the sandhills on the beach and the stony heights beyond, lay the camp of the emigrants. Nearly a thousand souls, on an average, were at present lodged there in military tents, but parties were daily moving off in long trains of bullock waggons, to proceed to their appointed places of location in the interior, while their place was immediately occupied by fresh bands, hourly disembarking from the vessels in the bay.

Nearly half the globe’s expanse intervened between us and our native land – the homes of our youth and the friends we parted from for ever, and that here, in this farthest nook of Southern Africa, we were now about to receive the portion of our inheritance, and to draw an irrevocable lot for ourselves and for our children’s children”

Thomas Pringle, Narrative of a Residence in South Africa. London, Moxon, 1835, reprinted in 1966.

The party camped on the beaches for the next three weeks, collecting equipment and rations. On the 5th June Hezekiah and some of the party moved off, aided by Cape Dutch farmers who had been requisitioned to transport the settlers. At Rietfontein Hezekiah was removed as head of the party by consent of the acting magistrate, a man named Captain Trappes, after complaints about his behaviour over money matters!

Orders were soon received for their removal to a new location on the Assegai Bush River, as the first site had been earmarked for a party expected under the leadership of Major General Charles Campbell. The new location was named Salem, meaning ‘peace’, and the only village founded by a settler party that still exists today. The community was notable among the settlers for ‘the order with which its affairs were conducted, both spiritual and temporal’.

At Salem, as one of the settlers, the then 9 year-old Henry Dugmore recorded in his diary: “We had now to take root and grow or die where we stood, but we were standing on our ground, and it was the first time that many could say so.” The Reminiscences of an Albany Settler by Henry Dugmore quoted on West Gauteng News – November 2005.

The settlement served several main purposes – one was to resettle the weavers and other trades-people who had lost their livelihood with the end of the Napoleonic War in 1815 and to establish English ‘villages’ in the border lands of the Eastern Cape province. The other was to ‘drop’ the settlers in as a buffer between British territory and African tribes who fought to retain their land (the previous year of 1819 had seen the Fifth Frontier War). The British Government gave the settlers very little support – some grain and equipment, but otherwise they were left to their own devices on land which was pretty much infertile. Droughts, floods and invasions typified the first few years. In March 1823 Hezekiah put his name to a petition which, among other things, stated that the 100 acres promised to each settler was woefully inadequate and that 4000 acres was better suited to subsistence of a farmer.

From a genealogical point of view the settlement became a minefield – young single women became ‘married’ to avoid paying a deposit – families lost children while others gained them. The other problem was that the lists that were drawn up at the beginning of the process bore very little relation to those who finally sailed.

Hezekiah Sephton died in 11 July 1842 at Lishuani Mission Station, Ficksburg, two years after his wife Jane.

Their eldest son Thomas was there in 1839, as I found the visit of James Backhouse, in July of that year, recorded on Missionary settlement in southern Africa 1800 – 1925 by Franco Frescura (from South African History Online)

“Lishuani, which is represented in the accompanying cut, consists of a humble mission-house, belonging to the Wesleyans: it is situated among great rocks, at the foot of a sandstone cliff. Near the mission-house, there are a few mat-huts, belonging to some Griquas, who removed hither from Old Bootchap, and in the vicinity there are several Basutu villages. In this neighbourhood a few of the people were also residing, who a few years ago, invaded the missionary-station at Lattakoo; they were under a Chief named Tlalela. Not thinking themselves safe in the Zoolu country, to which they returned, they fled into that of Moshesh, who received them peacably, and appointed them this place, where they now cultivate the ground in peace. Being but a short distance from Lishuani, many of them resort thither to listen to the glad tidings of salvation.

The people were invited to a meeting in the chapel, which is a large, hartebeest house. About seventy assembled, whom we addressed through the medium of T Sephton”.

From South African History Online – Missionary settlement in southern Africa 1800 – 1925 by Franco Frescura.

“Oh what a gay, what a rambling life a Settler’s leading!

Spooring cattle, doing battle, quite jocose;

Winning, losing; Whigs abusing; shopping now, then

mutton breeding;

Never fearing, persevering, on he goes!”

A G Bain, The British settler, quoted in Godlonton 1844.

Mark Dudley

© Mark Dudley 2007

Bibliography

Illustrations are used with permission from 1820 Settlers.com