As a child my granddad told us tales of his Uncle Arthur who he believed had emigrated to Australia and had helped to build the Sydney Harbour Bridge. While, as a family, we believed that he had emigrated, we had never seen any evidence to suggest that he might have worked on the bridge and were very sceptical.

When I first starting researching my family tree I found Arthur Reardon on the 1901 census living in Nottingham and employed as a blacksmith. I was a novice researcher and resigned myself to the fact that I would probably never find much more about him, but searched on line for his marriage anyway.

I found the reference for his marriage which took place in Nottingham in 1910 and ordered the certificate. I was fascinated to read that his wife’s father, Henry James Carpenter, was an astronomer. This was such an unusual profession in 1910 that I was able to find, via google, plenty of details about his career and eventually on the Curious Fox web site, I came across another researcher concentrating on this Carpenter family. His tree provided the names of Arthur’s daughter and granddaughter and recorded them as living in Sydney. I felt that I was getting closer, but the owner of the tree did not have any contact details and I had no idea what step to take next.

A while later I read a post on Genes Reunited suggesting that the Australian telephone directory was available on line and a quick look at the Australian White Pages provided me with an address. A letter was duly dispatched by airmail. I was not hopeful that I would have a response so carried on with my internet search.

I set about using Google to find out all I could about the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and discovered that it was constructed using a hot rivet method. I felt that as a blacksmith he would be experienced in this type of work and that perhaps I was getting closer to the truth.

Another post on Genes Reunited suggested that the online search facility of the National Archives of Australia was a very valuable resource for researching family there. I searched and was allowed to download, for free, several digitised files about Arthur and his wife Marcia during WW2. They were close associates of some prominent socialists and as such were considered to be of interest to the authorities.

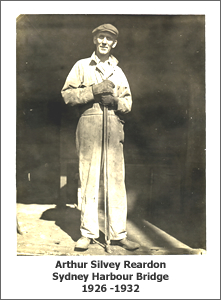

Wonderfully, within a few weeks Arthur and Marcia’s granddaughter emailed me. She confirmed that her granddad had been very proud to have worked on the bridge and that one of her earliest memories was ferreting around in the shed at the back of his house and bringing in a very large steel object with a knobbly type of head at one end. It was her introduction to her grandpa telling her about his days on the bridge and the rivet he had brought home as a memento. The family story had been true after all.

The story did not end there. Her mum, Eileen, was not in the best of health when we first made contact but, when prompted, remembered wonderful details from her childhood and stories that her parents had told her about the family she had left behind in England when she was only a few months old. She recalled memories that had been buried for many years and took great pleasure in her last few years in sharing them with her daughter. These memories form an invaluable part of the story of my family.

She told us that Arthur had suffered throughout his childhood with chest infections and diphtheria, and had been warned that the climate in England was making it worse. He and his wife Marcia decided, after the birth of Eileen, that they would immigrate to Australia. Eileen recalled that the family had sailed on a ship called the Otway and when, eventually, passenger lists became available online we were able to see that the family left London on 12 Jan 1912. The voyage was to last for 43 days and they were contracted to sail to Melbourne.

Arthur had believed Australia to be the promised land but could not find work. After many, many attempts Arthur chained himself to the Town Hall steps in Melbourne and demanded to be found work, which he was in Castlemaine, County Victoria. The family stayed there for a few years and then Arthur applied for work at the Rhodes Railway Engineering works in Sydney. During that time he attended the technical college, gaining qualifications in the manufacture of steel, in particular heat-treating.

In 1923, during the Depression, Arthur learned that steel workers were being recruited for the planned Sydney Harbour Bridge and in July of that year began work in the workshops at Milson’s Point on the northern side of the harbour where the rivets and steel cabling for the girders were cast.

In fact his career is remarkably well documented in an article that I found online using the Australian version of Google. I didn’t realise before but it brings up different results to the .com version. An Australian historian has published on line a collection of transcripts of retired people remembering their working lives. It was his intention to record what it had been like to be a worker in Australia in the mid 20th Century. One of his interviewees recalled his life working in engineering and made many references to the times that he had worked with Arthur Reardon. Arthur became one of Australia’s leading specialists in the heat treating of metals and was the first international member of American Society of Metals. I was proud to see that the article about Arthur was entitled ‘A Man of Principal’.

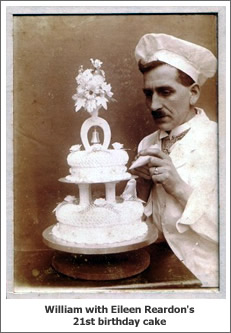

His daughter has sent wonderful photographs of Arthur working on the bridge and in amongst them also, a photograph of his brother, William. William was my great grandfather and had remained in Nottingham working as a master baker and confectioner. I remembered him fondly from my childhood and knew that he had owned a bakery in Nottingham. The photograph provides a lovely link between our families and shows William putting the finishing touches to a wonderful cake that he made and shipped to Australia for Arthur’s daughter, Eileen’s, 21st birthday in 1932. It arrived in one piece and Eileen still remembered it clearly although she was by now in her 90s.

Sadly Eileen passed on at Christmas last year but her daughter and I have become close friends over the miles. We have revived the tradition of exchanging gifts across the seas but are yet to try to ship something as ambitious as our forbears did.

Helen in Glos

© Helen in Glos 2007