A cause of curiosity to all and horror to some, I have a battered glass case in my living room containing a stuffed sparrow hawk with her bullfinch prey. Their theatrical heathland backdrop has been torn apart to reveal layers of Victorian small ads for, for instance, “two useful cart mares” and a Woking bakery flour bag. Despite these indignities the hawk’s bright glass eyes retain their fierceness. This is a macabre memorial to the collecting activities of the Lewcocks.

In an Edwardian nature memoir, Mrs Caldwell Crofton(1)refers rather bluntly to Mr J Lewcock as “a bird stuffer at Farnham” and his observations of crossbills in the nearby Alice Holt Forest in the late 1830s. Dr Jeffrey Wheatley, the Bird Recorder for Surrey, published in 2007 a definitive (and beautifully produced) volume on Surrey birding records and history (2). In this he describes the early collectors or observers of birds in the county. James Lewcock was one of a circle of local naturalists including Edward Newman, Thomas Mansell, Waring Kidd, J D Salmon and William Stafford. Newman started a periodical The Zoologist in 1843 and this has numerous reports from James on his observations of birdlife around Farnham. Newman was also author of “The Letters of Rusticius on the Natural History of Godalming” – which brought together much of the work of this group. Wheatley calls it “…the earliest avifauna to be devoted to Surrey or any part of it.” James is described in The Letters in 1849 as “the late James Lewcock” and, indeed, my great great great grandfather died in 1848 aged only 37.

In an email exchange Dr Wheatley draws attention to Bucknill’s 1901 Survey of Surrey Birds (3) where he writes. “Mr James Lewcock was an energetic naturalist living at Farnham; he carried on the business of a tradesman at that place and was a very skilled taxidermist. Mr Thomas Whitburn, the President of the Guildford Natural History and Microscopic Society, to whom I am indebted for the particulars of his life, tells me that he was about forty years of age when he died unexpectedly, in 1850 [sic].

Unfortunately he left no records or papers relating to his many naturalistic rambles, in some of which Mr Whitburn was his comrade, but he contributed several notes to the Zoologist on the Brambling, Crossbill, Ring-Ousel, Peregrine, Great Grey Shrike and other species; and apparently compiled for Rusticius and his coadjutors a list of Farnham birds which was freely quoted in their subsequent work …”

James shows up in a Mirror Magazine nationwide list of independent scientific societies of 1848 as the “active” Honorary Secretary of the Farnham Mechanics Institute (4). “This well-regulated and well-constituted institution … boasts able lecturers and as zealous patrons.” Doubtless the active Hon. Sec. was the one who submitted this well-spun information! Unfortunately the Mechanic’s Institute disappears after James’s death – perhaps evolving into the Working Men’s Institute which was created later? However, the Reverend William Moss, a migrant from Farnham, used it as his inspiration in founding a Mechanics Institute in Prahran, Melbourne in 1854 (5). This continues today.

Family history research of the Lewcocks had already placed James in our family tree. He was a baker who died in 1848 of scarlatina leaving his wife Jessamine with seven children, including George Albert aged 8 and Henry aged 6. James’s mother-in-law was a Mansell and it looks as if Thomas Mansell from Tilford (just outside Farnham) was his cousin. Thomas was also a baker – up the road in Guildford. Bucknill remarks that Mr T Mansell was “a taxidermist and naturalist of more than local reputation”.

Neville Lewcock draws attention to a lecture by William Stroud (1857-1942), a former master at Farnham Grammar, where he advises that “when Lewcock had found a rare bird he took it to his friend Mansell to be stuffed.” Easy then to imagine James, having completed the early morning shift baking his neighbours’ daily bread, collecting his dogs and setting off for a day’s bird observation and shooting to Frensham Pond. One of James’s reports to Newman reads: “On 24th October an uncommon looking bird was noticed by the person who rents the pond, wading in the shallow water. He succeeded in shooting it … and it proved to be a common spoonbill, a young bird … the crest being wanting. It is now in the possession of Mr Mansell, and in beautiful preservation.” Thomas survived James by many years. Stroud claims that he took a first prize for taxidermy at the Great Exhibition in 1851 and Thomas is recorded in the Farnham Herald in July 1868 as winning a prize of £1.11s.6d in the natural history section at the Farnham Working Men’s Institute 3rd Exhibition of Art and Industry for a display including “stuffed birds etc”.

Rather than birding, James’s younger sons George Albert and Henry got into bugs and beetles. I recently asked Alan Price, an entomologist and the former natural history curator at Oldham Museum, how he had got the bug-collecting bug. It seems Alan’s father had been an artisan baker (!) and they had a vegetable garden and orchard. Alan and his brother had had to pick the weevils out of the flour and the bugs off the plants. Perhaps that was also how George Albert and Henry, having to help their mother carry on the bakery after their father’s early death, but still too young to go off birding and shooting, got started?

Henry may not have been a very active bug-hunter. Nevertheless he wrote to the Entomologist Weekly Intelligencer (another of Newman’s publishing ventures) in 1858 aged 16 to report the capture of a specimen of sphinx convuvuli (a hawkmoth) “It was taken in a grocer’s shop, perhaps attracted there by the light.”

Great great grandfather, George Albert, on the other hand looks to have been obsessed with bugs as only a serious Victorian collector could be. He left Farnham at quite an early age. In 1851 he is found as a 19 year old apprentice compositor in Rochester, Kent, from where he moved to Islington to marry and raise a family. He made a series of contributions to the debates of the City of London Entomological Society in the late 1800s. He was also on the committee of the Society. In his discourses (they haven’t all been found or studied in any depth) he draws on collecting experience over 50 years, mostly in the home counties. He perhaps took advantage of the new and rapidly growing suburban rail network around London. He did, however, travel more widely and may, for instance, have been in Ireland in 1861 before his marriage in 1863.

In a talk given on the Donacia (water beetles) in December 1890 he refers to specimens he had taken in Walthamstow, Sunbury, Shepperton, Farnham, Wanstead, Hackney Marshes and Black Pond Esher. He advises of D Dentata “… some are brilliant grassy green and others of indigo-blue … The specimens [were] taken by me at Basingstoke canal in June 1887 … and by getting into the large patch [of pondweed] floating on the water I captured some fifty or sixty during the afternoon.” Must have made an entertaining sight. Middle-aged gent (46 at the time) up to his waist in the canal, picking jewel-like beetles off the reeds. No worries about Viles disease in those days! Another – “well received” – paper was a thorough survey of the Coccinellidae – nice to find you have an ancestor who was an expert in both water beetles and ladybirds!

So, two (or three) ancestors diligently collecting and recording birds or bugs. Victorian collectors could be astonishingly meticulous and it seemed reasonable to think that somewhere there might be catalogues and even specimens from the Lewcock collections of bugs, beetles and birds. Nothing has been kept in the family. Where to start?

The core national collections of bird and insect specimens were based on those of Lord Rothschild’s and are now held by the Natural History Museum (NHM) at his former home in Tring. Unfortunately his lordship’s wallabies, ostriches and other exotic creatures no longer roam Tring Park. However, the public galleries still have atmospheric tableaux of stuffed creatures from whales to tiny mites in glazed and beeswax polished wood cabinets. Well worth the visit. NHM also has all necessary modern research and educational facilities. Although they don’t have any Lewcock records themselves, their archivist, Lisa di Tommaso, kindly passed on my request for information to their ornithological and entomological experts (for example Dr Wheatley) and suggested other directions to look.

Progress was fastest in hunting the bug-hunting. In the course of half a century collecting, George Albert would have exchanged many specimens with fellow enthusiasts. The NHM entomologist was able to flag up an 1896 auction of George Albert’s insect collections. It was usual at that time for a purchased collection to be broken up, any complementary specimens being kept by the purchaser and others sold on. Googling had already discovered scattered Lewcock bug or beetle specimens in the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff (6) which were acquired from the collection of W Chaney and The Tullie House Museum in Carlisle (7). The latter has a longhorn beetle taken by GA in Walthamstow in 1892. Frank Balfour-Browne writing in the Irish Naturalist (8) in 1912 suggests that when George Albert’s collections were sold the water beetles were “purchased by a collector on the Continent.”

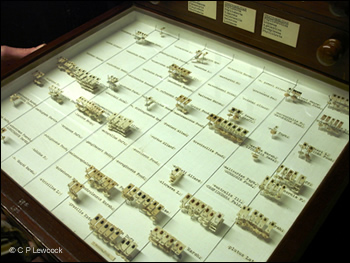

In 1924 Oldham Museum bought the collection of C G Hall of Deal which included some of George Albert’s specimens. Email exchanges with Curator Alan Price confirmed that they did have the Hall Collection and that the catalogue did indeed list some of George Lewcock’s specimens. An inspection visit was agreed! Oldham Museum has recently had a new extension and the older parts of the building are waiting refurbishment and refitting (and further funding!) for, amongst other things, the natural history collections. Alan escorted me to the basement where the natural history collection is stored temporarily. Amongst a wonderful organised “jumble” of stuffed creatures – including parrots and a magnificent golden eagle – mousetraps, silverfish traps and the smell of camphor and other preservatives he showed me two glossy redwood twelve drawer cabinets with brass fittings. These were the Hall collection, including 5000 or so bugs and beetles ranging from great stag beetles to almost invisible mites, all equally carefully pinned and preserved. Alan set me up with a table, a mug of coffee and the catalogue. There were in all about twenty Lewcock specimens, very clearly listed and including several ladybirds! From his hand-written notes it looks as if Hall had obtained some specimens directly from George Albert. So, some tangible contact with an ancestor!

The birds were more difficult, doubtless because that collection would have been fifty years older. Email contact was made with the several museums around Farnham including Haslemere, Farnham itself, Godalming and Guildford, with the County Archivist in Hampshire and the Surrey History Centre. Also Charterhouse School, Godalming which has a large collection of bird specimens. All made a rapid response and if they couldn’t do other they made helpful suggestions. Some possible contacts, like the large private collections now held in some National Trust houses, I still have to follow up.

One of James’s circle, J D Salmon, had joined the Botanical Society – later combined in the Linnaean Society – after he left Farnham for London in 1851. Ann Laver, Research Coordinator at Godalming Museum drew attention to a note in the Zoologist of 1901 about Salmon’s egg collection having been auctioned in 1860 – “some went to Norwich”. Norwich Museums Service and the Linnaean Society were, however, unable to help.

The Hampshire Senior Keeper of Natural Sciences, Christine Taylor, happened to have carried out some research on early taxidermists in Hampshire – based mainly on trade directories – but hadn’t come across James. However “Will keep a look out – am intrigued as [he] would be one of the earliest known taxidermists in Hampshire.” An interest echoed by Martin Dunne of the British Historical Taxidermy Society. Duncan Myrilees, a Heritage Team Leader at the Surrey History Centre advised: “Many years ago, possibly about 25, I was assisting in clearing (or, more properly searching) the attic at Godalming Library in search of historical material. Amongst the collected junk were a number of stuffed animals and birds. In fact, on opening the loft lid a stuffed squirrel threw itself at my colleague, who acquired a nasty rash as a result. The collection was later cleared from the attic by Godalming Museum staff…”

Back then to Ann Laver who found a record of the incident and confirmed that they had had a sparrow hawk, song thrush and two red squirrels. They had no information where the specimens had come from. Not being a natural history museum, they had sent the specimens on to Dr Pat Morris, an expert in historical taxidermy in case he could make use of them. Contacting Dr Morris, he had inspected the sparrow hawk but it wasn’t a valuable specimen and wasn’t in great condition. He had passed the bird to a colleague for possible use in demonstrations of smaller birds mobbing a bird of prey. He had however taken a photo of some of the display stuffing including a flour bag from a Woking bakery! He had also kept the display case. The Woking bakery sounded like a very hopeful sign!! Dr Morris agreed to retrieve the bird so that I could come and see if it was worth keeping.

Visiting Dr Morris to inspect the sparrow hawk I was also able to see some of his finely restored displays of stuffed birds. They were extraordinarily vivid and colourful and you could see how they must have brightened up a Victorian or Edwardian parlour. We discussed how sad it is that so many museums have ditched or put into store their collections of stuffed creatures which – whilst we should regret the mass slaughter of which they are the result – still provide an educational resource and important reservoir of scientific information about changes in animal populations – not least through the DNA they contain.

We agreed that as a (possible) family relic it would probably be better for the sparrow hawk and its prey to be held by myself rather than being torn apart by sparrows! Home in triumph with a sparrow hawk (and bullfinch). However …!

The birds had originally been placed against a painted scene and on a raised ground formed of crumpled paper (including the flour bag) and gummed moss and lichen to simulate a heathland setting. The other packing was newspaper. Spreading this out I discovered reports of events in 1887!! Some forty years after James Lewcock had died! So these are most unlikely to be his birds!

The trail hasn’t run cold yet. I still have to follow up the other collectors James was associated with and, as more and more information – from past auctions, private catalogues etc. comes online, it is likely that something new will turn up. In the meantime (history cannot be wiped like a tape-recording) the sparrow hawk and bullfinch have now become a small part of my own story.

Future Lewcocks may wish to shake their heads over this tangible evidence of another form of obsessive eccentricity – genealogy research!

C P Lewcock

© C P Lewcock 2010

SOURCES and FURTHER READING

1. Milman H 1900 Outside the Garden The Bodley Head. London

2. Wheatley J J 2007 Birds of Surrey Surrey Bird Club

3. Bucknill J 1901 The Birds of Surrey…

4. The Mirror Monthly Magazine Vol. IV July-to December 1948 Kent and Richards, London

5. Victorian History Library: Prahran Mechanics Institute

6. Kirk-Spriggs A H and Mendel H 1994 A Catalogue of British Elateroidea (Coleoptera) in the National Museum of Wales: Entomology Series Number 3

7. Tullie House Museum Virtual Fauna Website: Collections

8. The Irish Naturalist Volume XXI 1912 pp1,2

Google Books: The Letters of Rusticius on the Natural History of Godalming

Natural History Museum at Tring

Norfolk Museums and Archeology Service

Hantsweb: Taxidermy Collections

The British Historical Taxidermy Society

Personal communication (emails) September 2009