When you first start researching your ancestors, it is often fairly easy to get back to the early-to-mid 19th century using birth, marriage and death certificates in conjunction with census information. To get back to generations that pre-date ‘official’ registration, the International Genealogical Index (IGI) on the FamilySearch website can be a useful aid to finding baptisms. So, in common with most researchers first setting out, one branch of my husband’s tree was soon constructed back to his 3x great grandfather Thomas Attlebury, baptised on 21st October 1821, in Peel-by-Bolton (now known as Little Hulton).

Also using the IGI, we found that Thomas had several brothers and sisters. There we have had to leave this line, as we have not yet been able to find their parents’ marriage, although Thomas’ father John was baptised in the same church in 1798. Having such an unusual surname has proved to be both a blessing and a curse. There don’t seem to be any other Attleburys around the Bolton/Worsley/Salford area, but the name is frequently misspelled, thereby taxing anyone’s imagination when searching online sources!

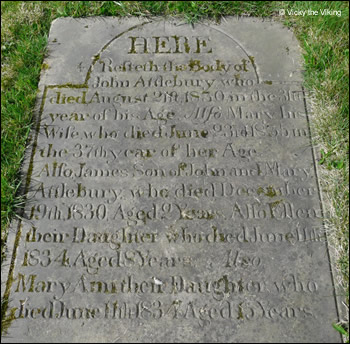

In my quest for more information on the family, I was fortunate to come across the Lancashire On-Line Parish Clerks website which showed Thomas’s father John’s occupation as ‘collier’. It also sadly gave burial details for some of the family, including 8 year old Ellen and 15 year old Mary Ann, both buried on the same date in 1834. Reflecting on how this family probably lived, I thought this was most likely due to some infectious disease, a sad but almost inevitable consequence of the conditions of the time. The dates were duly entered into the tree, and I turned my attention elsewhere.

Over the following months, I managed to fill in a few more details about this family and a sorry picture emerged. John had died in August 1830, aged only 31, leaving his wife Mary – who was also pregnant – struggling to bring up five young children. A further tragedy occurred only four months later, when James, the youngest son, died. The baby she was carrying, a girl, was born the following spring. Life and times were hard and Mary must have had to send the children out to work as soon as they were old enough. We then have the devastating loss of the two girls in June 1834. Mary herself died just a year later, in June 1835. At this time Thomas, the oldest surviving child, was not yet 14 years old, and the two younger girls then aged about 10 and 4. The 1841 census has young Thomas living in lodgings in Little Hulton and working as a coal miner. The older of the two girls, then aged 15, is in Manchester Infirmary, with her occupation given as ‘collier’, and her younger sister is living with unrelated family in Bolton.

At this time there are two other Attleburys living in Worsley – Thomas and Betty, who are probably John’s parents, both of whom died in January 1844. I often wonder whether they would have helped to bring up Thomas and his young sisters and why they are not living with any of the children in 1841.

Thomas snr. was interviewed for the 1842 Royal Commission Report on The Employment of Women and Children in the Mines. He said that he had been working in the mines for over 60 years, since he was a young child. In this era, it was quite common for young children to be employed in the mines, sometimes from the age of 5 or 6. The mining conditions of this period have been vividly brought to life in a display at the National Coal Mining Museum at Wakefield , which also has a copy of the report in its library. This report led to the Act of Parliament which made it illegal to employ women and children underground.

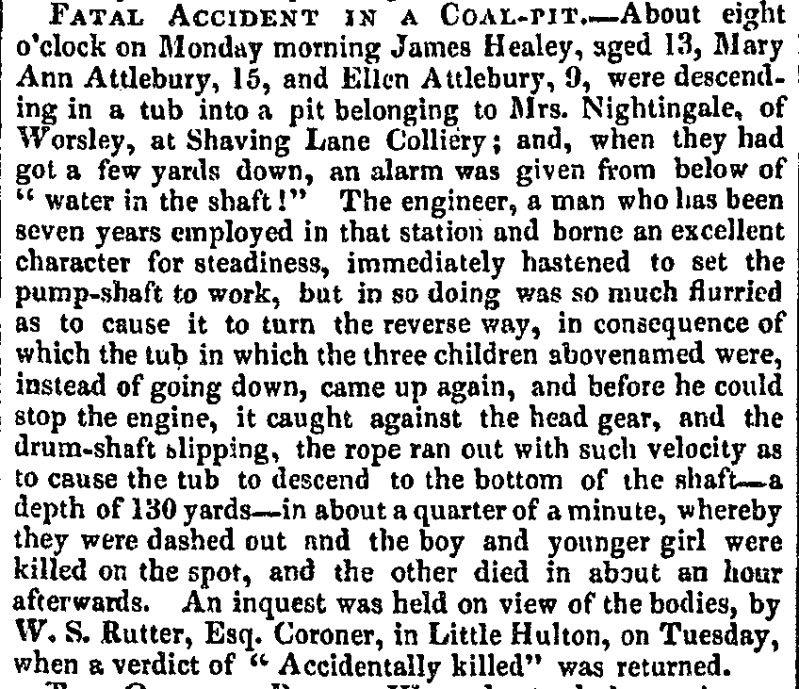

Fast forward a couple of years, and the appearance of online searchable 19th century newspapers on the British Library website. Initially I was looking for another of my husband’s ancestors, a reprobate who was in the House of Correction on the 1851 census… then (as you do) idly typing in all the rarer surnames in our trees, I got some hits for Attleburys. I opened up a document from the Derby Mercury from June 1834 and I was horrified by what I read there. I knew immediately that the report was about my husband’s family.

Three young children – James Healey, Mary Ann Attlebury and Ellen Attlebury – had been killed in a mining accident. The winchman had lost control of the tub in which they were descending into the pit. The tub had smashed against the head gear then fell rapidly 130 ft down to the bottom of the shaft. The children were thrown out, the two younger children were apparently killed outright but the older child, Mary Ann Attlebury, lived for a short while. Another more detailed report I later found in the Manchester Times said that Mary Anne had been taken home and died there. The inquest returned a verdict of ‘Accidentally Killed’. All three children were buried the next day, the two Attlebury girls in Little Hulton. For Ellen, it was 8 years to the day since she had been baptised at that same church.

Both my husband and I have several generations of coal miners in our lines, but mining is something we associated with strong men, not small children, and girls at that. It was shocking to realise that incidents like this were not unusual, and we can only be grateful that the 1842 Royal Commission report put an end to this shameful waste of young lives.

Vicky the Viking

© Vicky the Viking 2010