Be warned that this article spans several generations – you may want to make some coffee before starting!

Although seven of my great grandparents were from Yorkshire, I have one German great grandfather, who emigrated to Britain in the 1890s.

My half-German grandmother was proud of her German ancestors and stayed in touch with many of them for as long as possible. My grandmother wrote down some memories, stories and relationships, but it is quite amazing how much I have rediscovered, which did not pass down through the family.

For this I am particularly indebted to a certain (German) member of this forum, and her mother, who have researched a part of my family tree, in their town in Saxony, for their local history.

Ancestors in Posen (Poznań), Poland

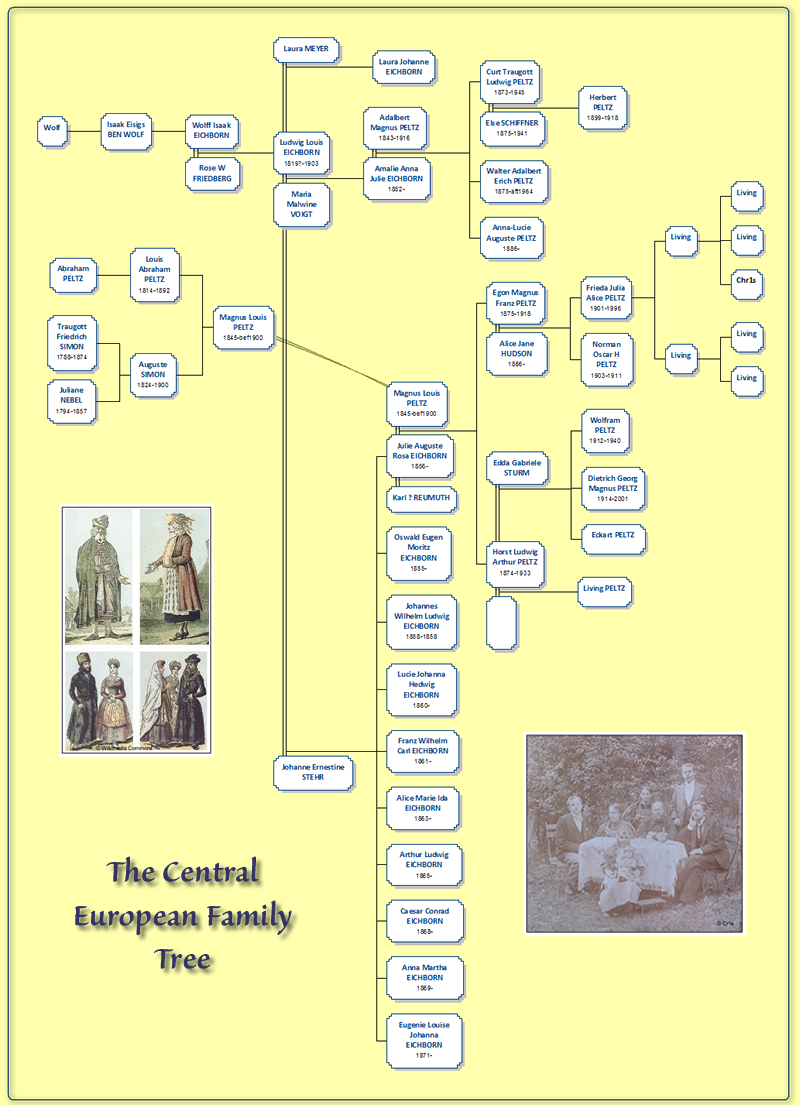

|

We pick up the story with my great x6 grandfather, although I know precious little about him, beyond his first name, Wolf. He must have been born around 1730 (give or take 20 years!). He was a Jew, living in Poznań (Posen), Poland, and I think he must have had some standing with both the Jewish community and the provincial authorities of Poznań, for the reason detailed below.

The city of Poznań (or Posen, during German rule) is one of the oldest cities in Poland, and was the capital of the Greater Poland region until it came under the dependency of Prussia in 1793, when its administrative area was renamed as South Prussia.

Jewish migration to Posen started as early as the 11th century, as Jews fled persecution in Germany. Later periods of migration followed anti-Semitic outbursts in Germany in the 12th ~ 15th centuries. Throughout this time, Poland was a haven for Jews. During the Greater Poland Uprising of 1806, Polish soldiers and civilian volunteers assisted the efforts of Napoleon by driving out the occupying Prussian forces. The city became a part of The Duchy of Warsaw and became the capital of the Poznań Department. In 1814, after Napoleon’s defeat, Greater Poland was returned to Prussia and became the capital of the Grand Duchy of Posen.

In the early 1800s, in the Kingdom of Poland, Jews were required to take surnames, by a Russian Government mandate. According to FamilySearch Research Wiki: Jewish Names Personal, Prussia extended the family name requirement to Posen in 1833. Prior to this, most Jews in Posen did not use fixed surnames!

Tracing ancestry further back becomes challenging, when Jews had no hereditary family name. To add to this difficulty, there was a substantial migration of Jews westwards in the latter half of the 19th century, both to Posen and from Posen to Germany, before the Jewish population of Poznań was virtually wiped out and the synagogue destroyed in WWII.

What little I know of Wolf is from his son, my great x5 grandfather, who was Isaak Eisig ben Wolf (‘ben Wolf’ meaning ‘son of Wolf’). Isaak Eisig was born around the 1760s, in Poznań, and was appointed Shtadlan for Poznań in 1783, when he was still a young man. This suggests that his father had standing in the community or Eisig succeeded in building an impressive reputation at a young age, as Wikipedia defines the Shtadlan as:-

A Shtadlan was an intercessor figure starting in medieval Europe, who represented interests of the local Jewish community, especially those of a town’s ghetto, and worked as a “lobbyist” negotiating for the safety and benefit of Jews with the authorities holding power. Typically, a Jewish community (kehila) governed its own internal affairs. The interactions with the outside society, such as tax collection and enforcement of various restrictions and compulsions imposed on the community, were arranged by an internal governing board.

The Shtadlan emerged to prominence in the 17th century as an intermediator between the Jewish community and the outside government in control. The position was appointed by the government, and could even be named as a royal official. Although he officially represented the Jewish community only, the Shtadlan became a tool of the government.

|

Isaak was in office for 45 years, rising to a comfortable salary of 30 guilders per week (if I understand the German text correctly). During those 45 years, he would have represented his community firstly under Polish sovereignty, then Prussian, then Napoleonic France and finally back to Prussian. In 1828, Isaak Eisig resigned and the post of Shtadlan for Posen was dissolved.

Isaak Eisig’s son, my great x4 grandfather, Wolf Isaak Eichborn (or Wolff Jitzchak Eichborn), was born in 1792 in Poznań. From 1815, at the age of 23, he wrote many petitions and essays on improving the civic conditions of the Jews. He was particularly concerned with the education of poor Jewish school children. As a young man he was successful in business until 1818. In 1816, the German language and culture was introduced and industry declined due to competition with industrial Prussian provinces, and most Jews supported themselves through agriculture. This may have been the reason that he turned from business to interpretation and translation, making use of his fluency in German, Polish and Hebrew and becoming Interpreter for the Posen Municipality and a translator of the Hebrew scriptures into German.

He must have been successful, because in 1832, his land was valued at 10,000 thaler, putting him amongst the wealthiest Jews in Posen.

He was one of the fiercest opponents of the election of Rabbi Akiba Eger as Chief Rabbi for Posen, in 1815, but when the rabbi died in 1837, Eichborn wrote his obituary and despite differing views on many issues related to the further development of Judaism, he wrote of Rabbi Eger’s outstanding piety, humility, erudition, knowledge of the Talmud, intellect etc. In a letter, signed by Wolff Eichborn, amongst others, protesting about the appointment of Rabbi Egers, there is a reference to whether the debt-ridden Jewish community could afford to spend 1400 thaler a year (or about 50 guilders per week) for payment of the rabbi.

Around the early 1800s the Jewish world was divided between enlightenment and orthodoxy. Traditional Jews tried to suppress modernity, and enlightened Jews regarded the traditionalists as their enemy. The Reform movement sought to adjust Judaism to modern European civilisation without infringing its basic principles. Laymen in several German cities wanted to make their worship in the synagogue – or temple – more like the grand services of their Protestant neighbours. The first Reform congregation was established in 1818 in the Hamburg Temple, with sermons and prayers in German and an organ to accompany the prayers. The bar-mitzvah was extended to girls, and women and men ceased to be separated at services.

In 1834, an ‘Israelitischer Brüderverein’ was established in Posen. One of the leaders of this association was ‘Wolff J. Eichborn’, who delivered the first sermon in German. In Posen, in 1834, Wolff Eichborn edited and wrote the introduction for a book with the snappy title “Sammlung der die neue Organisation des Judenwesens im Grossherzogtum Posen betreffenden Gesetze, Instruktionen, Rescripte usw.” or the collection of relevant laws, instructions, rescriptes etc. of the new organisation of the Jews being in the Grand Duchy of Posen.

Ludwig Eichborn – banker, bankruptcy administrator and land-owner

|

Wolff’s son, Ludwig Eichborn, my great x3 grandfather, was born in Posen in 1810, 1818 or 1819 (to be confirmed, depends on source – 1818/9 seems most likely!). However, from 1844 he was co-owner of a brick and pottery factory in Velten (about 15 miles NW of Berlin), opened by Johann Ackermann in 1836. In 1848 he is listed in the Berlin address book as a merchant and pottery factory owner. By 1859 he is listed as merchant and bankruptcy administrator of the municipal court and circuit court (Kaufmann und Concurs-Waren-Verwalter beim Stadtgericht u. Kreisgericht). In 1863, in addition, he is listed as Lotterie-Ober-Einnehmer (chief lottery collector?).

He became a father in 1848, with a daughter Laura Johanna Eichborn. I don’t know if he was married to her mother, Laura Meyer, but less than four years later he had another daughter, Anna Julie Amalie Eichborn, with Maria Malwine Voigt. Again I don’t know if they were married, but in both cases the girls took the surname Eichborn. I know that he was christened in 1852 (only 7 ½ weeks after the christening of his second daughter) and then married Johanne Ernestine Stehr in 1854, in Berlin.

From the entry for Ludwig’s christening, in the records of the Jerusalem Kirche in Berlin (an evangelical church in the Prussian Union), we know that his mother was Rose W. Friedberg. Whether he was truly converted to Christianity, or christened in order to marry Johanne, or because it would be more difficult to follow his career path as a Jew, I will probably never know. But all his (12) children, that I am aware of, were christened in Berlin. He and Johanne proceeded to have a further ten children between 1855 and 1871, including my great x2 grandmother, (Auguste Rosa) Julie Eichborn. Johanne was married four times, and Ludwig was at least her second husband. I suspect that it was quite unusual to divorce three times!

My grandmother wrote: “Frau von Eichborn was evidently a “woman of the world” – was married 4 times – but my grandmother’s father was Herr von Eichborn. Once my great grandmother gave a dinner-party – her present husband + the three other husbands (previous ones) were all invited guests. According to legend she was a selfish type & wanted all her daughters to be married (early).”

Presumably well-informed by his role as bankruptcy administrator, Ludwig bought a considerable area of land in and around Zakopane at an auction in Berlin on 31st December 1869. This land cost 400,000 Guilders, which I believe to be equivalent to a few million pounds today (although price comparisons across centuries are not very reliable) ! (As a comparison, Wolff Eichborn was viewed as wealthy in 1832, with land worth 10,000 thaler (17,500 Guilder), and 1,500 Guilder was a comfortable annual salary in 1828).

Zakopane is a town in southern Poland, at the foot of the Tatra Mountains. It is informally known as “the winter capital of Poland”, as it is the most important centre in Poland for mountaineering and skiing, with around 3 million tourists visiting annually. In 1676 Zakopane was just a village of 43 inhabitants, and in 1824 it was sold to the Homolacs family together with a section of the Tatra mountains. Ludwig Eichborn succeeded the Homolacs as owner of Zakopane, apparently owning the village and a part of the Tatras, and by 1889 Zakopane was a climatic health resort of 3000 inhabitants.

Ludwig became Lord of the Manor, and his land at Kuźnice, near to Zakopane, included an industry to process iron ore mined in the Tatras. Unfortunately, this industry started to diminish and the smelters were turned off in 1879. (Nowadays, Kuźnice is the base station for a cable car taking tourists, skiers and snowboarders into the Tatras). Texts say that Ludwig (and later his son-in-law) were devastating large parts of their forest lands, but that he achieved good things for Zakopane and for the tourism development of the Tatras.

In 1870, at Ludwig’s invitation, a German photographer, Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, arrived in Zakopane and dedicated an album of photographs ‘Die Hohe Tatra’. Ludwig Eichborn supported the installation of an autonomous municipality for Zakopane and, from 1872, a ‘town council’ composed of twenty members. In 1873, Ludwig was instrumental in founding the TT (Towarzystwo Tatrzańskie), now known as the PTTK (Polskie Towarzystwo Turystyczno-Krajoznawcze), which aims to study the Tatra mountains, make them open to the people and to protect the wildlife. His signature appears on the first statutes of the Tow. Tartra. This association is still thriving today. Included in his ownership was the Dolina Rybiego Potoku valley, with Morskie Oko, the largest and fourth deepest lake in the Tatras.

Ludwig donated (or traded?) a plot of land beside Morskie Oko, with free timber for the construction of the second hostel in 1874, although this had to be replaced after it burned down in 1898.

|

From 1875~1879 there was a TT Museum, in premises donated by Ludwig, who also donated a collection of minerals in 1876. In 1877 Ludwig spoke publicly about the need to protect the chamois and various matters related to tourism in the Tatras. Ludwig supported the development of Zakopane itself and Karl Kolbenheyer dedicated the first three editions of his guide ‘Die Hohe Tatra’ (1876, 1880, 1881) to Ludwig Eichborn. In 1880, Ludwig passed this land on to Magnus Peltz, his son-in-law.

Ludwig was also active in Berlin during the 1870s. During this period from 1870 to 1880, Ludwig still appeared each year in the Berlin address book, described variously as combinations of banker, chief lottery collector, landowner and estate owner. According to his obituary (found on the internet), he bought the ‘Lehnschulzengut’ and associated lands in Reinickendorf West and the address where he lived in 1859, in the ‘Linkstraße 29’also belonged to him. In 1866, with Albert Werkmeister and others, he founded the Westend K.G.a.A., which built the estate to the west of Charlottenburg in 1870. He projected the future paths of the roads on his land plan and sold the parcels of land to small artisans, labourers and farmers, especially from Berlin.In 1873 Eichbornstraße was created as a project and was also named after him, in 1875, during his lifetime. Eichbornstraße ran from Scharnweberstraße to the Eichbornstraße S-Bahn station. It extended onto Charlottenburger Straße, which proceeded to the main road in Wittenau (now Alt-Wittenau). Both roads (and the S-Bahn station) were renamed Eichborndamm in 1937.

Doctors and doll manufacture in Schneeberg, Saxony

|

Meanwhile we join my great x4 grandparents in Schneeberg, Saxony, whose grandson married Ludwig Eichborn’s daughter, to become my great x2 grandparents.

The town of Schneeberg, in Saxony, Germany, has a history stretching over 500 years, shaped by mining more than anything. While searching for pewter and iron, in 1470, a miner discovered pure silver, and in 1477 a 20 ton block of silver was found. This was the start of mining in Schneeberg and it is no surprise that the area came to be known as the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge). The original silver mining also yielded cobalt, bismuth and, later, uranium.

My great x4 grandfather, Traugott Simon, was not a miner but a braid maker and trader. Born around 1788, he married Juliane Nebel (born 1794) and they had two daughters – Marie and Auguste. Traugott was aged 85 when he died, outliving his wife, who died aged 63, in December 1857.

Marie married Richard Reumuth. They had at least nine children, as there is a reference in the Schneeberg archives to one of them (Max Ewald Reumuth) being the ninth. We don’t have a complete list of their family.

Marie’s sister, Auguste, my great x3 grandmother, was born in 1824 in Schneeberg, and, aged only 17, she married Louis Peltz, ten years her senior, on 29th July 1841. Louis was a wound doctor and surgeon, the son of Abraham Peltz.

Louis and Auguste Peltz had two sons, Adalbert (full name Magnus Adalbert Peltz) and Magnus (full name Louis Magnus Peltz). Adalbert was born on 16th May 1843, and Magnus was born on 4th March 1845, both in Schneeberg, Saxony. While her boys were both still young, Auguste started a business producing dressed dolls. The first factory for her doll manufacturing is still existence, in Schneeberg, as a museum. (Unfortunately, not a museum to her business but a museum of miners’ folk art, exhibiting old wood carvings, Christmas pyramids and also models of vertical tunnels). The business grew into a second factory (see photograph, courtesy of U. Schnürer), which was finally demolished in 2008. From its small beginnings, it grew into a factory employing hundreds of workers. The factory employed seamstresses, but we don’t know if the dolls’ heads etc. were manufactured or bought in.

The Peltz and Eichborn Descendants

Auguste’s two sons, Adalbert and my great great grandfather, Magnus, married two half-sisters – Amalie (or Emalie) and Julie Eichborn. So Adalbert and Emilie are my great x3 aunt and great x3 uncle both by blood and through marriage!

In August 1872, Adalbert married Anna Julie Amalie Eichborn, who was born 22nd February 1852 in Berlin. Their children, Kurt (full name Traugott Ludwig Kurt Peltz, b. 2nd October 1873, Schneeberg, d. 1945, Dresden) and Walter (full name Adalbert Erich Walter Peltz, b. 14th May 1875), were cousins of my great grandfather Egon Peltz.

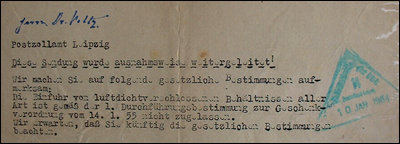

Kurt became a doctor. His son, Herbert, died in WWI in Bailleul, aged only 18. Kurt himself died during the Allied bombing of Dresden in 1945, outliving his wife Else, née Schiffner, who died in 1941, aged 65. Walter also became a doctor, but a doctor of chemistry, and he must have been the ‘Uncle Walter’ who my grandmother corresponded with. When Germany was split into East and West, after the war, Leipzig was in the GDR (East Germany), and my grandmother used to send parcels to Walter. It seems that one parcel contained sealed containers (perhaps tinned food), which was against the rules:

| “Herr Dr Peltz Leipzig postal customs This consignment was forwarded by exception! We bring your careful attention to the following legal provisions: The import of hermetically sealed containers of any kind is not allowed according to 1. Rules for Gifts Decree of 14. 1. 55. We expect that you will follow the statutory provisions in future.” |  |

Walter would have been aged 88 at the time of this letter.

In 1873, the year after Adalbert married, his brother Magnus married Auguste Rosa Julie Eichborn, who was born 27th August 1856, in Berlin. Their children were Horst (full name Horst Arthur Peltz, b. 26th March 1874, Schneeberg) and Egon (full name Egon Magnus Franz Peltz, b. 1875, Schneeberg).

My grandmother wrote: “my grandmother, Julie von Eichborn, married at 16 years to my grandfather Magnus Peltz who was 31 years. My grandmother told me when I visited her in Glauchau that before her marriage – on her birthday – her future husband made her a present of a horse – which was being paraded under her bedroom window when she awoke, presumably by a groom. She was delighted. She did at some time ride in die “Unter den Linden” – in Berlin. She had two sons by the time she reached 19 years & then no more. Horst Peltz, my uncle, + my father Egon Magnus Franz Peltz.”

|  |  |

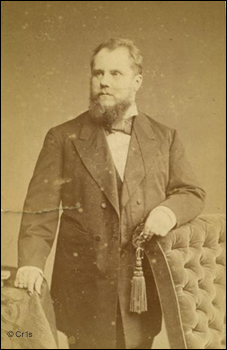

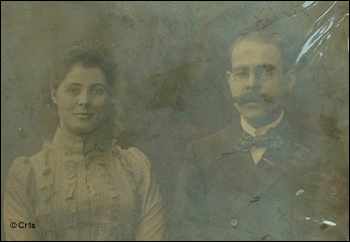

| Adalbert Peltz ~ my great x3 uncle | Julie Eichborn ~ my great x2 grandmother | Magnus Peltz ~ my great x2 grandfather |

In 1880, Ludwig passed ownership of the land in Zakopane on to Magnus, his son-in-law, who built a paper-mill there around 1881, to manufacture cardboard, pulp and wood. Also, Magnus inherited the doll factory in Schneeberg from his mother, Auguste, in 1876. We don’t know why Magnus (out of all Ludwig’s children and their spouses) was given the land in Zakopane or why he received ownership of the doll factory in preference to his older brother.

Magnus tried to make a go of the industry in Zakopane, by building this cardboard mill, to replace the ailing iron-ore industry. This is said to have damaged the local ecosystem, through deforestation for both fuel and raw material, and the later transformation from industry (based in Kuźnice) to tourism (based in Zakopane) helped to repair much of this damage and conserve the area.

The story passed down through my grandmother was that Magnus’s step-father-in-law (one of Johanne’s ‘other’ husbands) borrowed money, with Magnus as the guarantor. When the loan was called in the step-father could not pay, and Magnus, as guarantor, was served with a bankruptcy order in 1883, and was forced to sell the doll factory in 1884. This cannot have been enough, as he then had to sell the land in Zakopane at auction in 1888.

|

My grandmother wrote: “when she (Julie) was in her late 20s – her step-father asked my grandfather to be a guarantor for a sum of money he must have borrowed – he never paid it – and my grandfather had to pay it all instead – it bankrupt him. He then went to Pomerania & started a saw-mill. This place was away in the country, & my grandmother would not go with him – she told me she loved the life of the town. (She told me this, & at the same time, how much she had regretted her action, which she said was very wrong).”

So Magnus planned to move to Pomerania (?) and open a sawmill, but Julie refused to go with him and they parted. This suggests that Magnus was not left penniless by the bankruptcy! We don’t know what happened to Magnus after this, except that he is described as ‘deceased’ on Egon’s marriage certificate in 1900, and at Auguste’s death, also in 1900.

Magnus and Julie were divorced on 25th August 1886. I have found no more definite information about Magnus or Ludwig after this date, apart from the internet entry that Ludwig died in 1903, in Berlin. My grandmother told us that Julie moved to Glauchau, in Saxony, and re-married to a Karl Reumuth. Magnus had at least nine cousins with the surname Reumuth, probably born in Dresden, Saxony, so it is possible that Karl was one of Magnus’ cousins. An entry for Horst confirms his mother’s name as Julie Reumuth, and describes his father as a “Kaufmann in Holzkirchen”, but no further information is forthcoming from the Holzkirchen south of Munich, but there are several different communities in Germany that are called Holzkirchen.

Magnus and Julie’s two sons pursued quite different lives. Egon emigrated to England, aged around twenty, or in his early twenties, whilst Horst followed a successful industrial career in Germany. Horst is listed as a director of Linde AG, in 1926/7, and as a director of Sauerstoffwerk (Oxygen Plant) Linde, Magdeburg, in the 1930s. He died on 16th February 1933, in Berlin.

Linde AG is a large industrial company, with products including industrial gases, engineering and construction, built up from pioneering refrigeration in the 1880s. By the 1920s, there were approximately 2,000 ~ 2,500 employees, rising to around 40,000 more recently.

Horst married Edda Gabriele Sturm. My grandmother met their three sons (Wolfram, Dietrich and Eckart) in the 1920s. Eckart died in his teens, and Wolfram (b. 22nd October 1912) died whilst serving in the Luftwaffe. It appears that he was an Oberleutnant, and he fell on 23rd May 1940 in L. Neuville. His death is documented as record number 311 at Riesa, Saxony.

My grandmother told us that Edda divorced Horst for adultery, effectively breaking all contact with him, but it turns out that he had another daughter. This daughter and her family are still living in Germany.

Major General Dietrich Peltz

When celebrities appear on ‘Who Do You Think You Are’, they usually admit to a fear of discovering something terrible about an ancestor – perhaps like my first cousin, twice removed, Dietrich.

There is a lot of information about the military career of Dietrich (b. 9th June 1914), who, although he gained his pilot’s licence at the age of 18, worked at Daimler-Benz during 1933/34 with the intention of becoming an engineer, before joining the army in 1934, then transferring to the Luftwaffe. He made a name for himself for his precision bombing and attack strategy – leading 102 missions against Poland and France, without his squadron suffering a single loss. He was awarded the Iron Cross, First and Second Class, for his success in the Polish campaign.

Early in the French campaign his squadron encountered enemy fighters, and after shooting down a French fighter, a Stuka had to crash land behind enemy lines. After landing his Ju 87 bomber, Dietrich took a Fi 156 (short take-off and landing aircraft) and fetched the crew of the crashed Stuka. For actions during the campaigns in Poland, France and Britain, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross in October 1940.

In the Russian campaign of 1941, he developed superior bombing techniques, achieving extraordinary success against precision targets and his highly accurate results earned his decoration with the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross, which was presented by Hitler, in person, on 1st January 1942. A photograph of the presentation by Hitler (Dietrich Peltz is on the right) can be seen at: ullstein bild. (You can find the picture by putting peltz into the left hand search box. You can use the site in English from the link in the menu on the right.) In July 1943 he became only the 31st recipient (out of about 160) of the Swords to the Knight’s Cross.

After the destructive attack on Hamburg in July 1943, Göring confronted Hitler with the need to build up the fighter defences. Instead Hitler ordered a retaliatory bombing campaign against England, despite the Luftwaffe bombing force being far weaker than it had been during the Battle of Britain in 1940. Dietrich Peltz, then 29 years old, was promoted to Major General and appointed ‘Angriffsführer England’ (attack leader England). During this ‘Baby Blitz’ from January to May 1944, the Luftwaffe attacks accomplished little and later in 1944 most bomber crews were retrained to the fighter role. In March 1945 he took command of what was left of the entire Reich Defence Force. At the end of the war, he was the youngest general in the Wehrmacht, aged only 31.

He worked with Göring, but he was not called to the Nuremberg trials. It seems surprising that both Wolfram and Dietrich joined the Luftwaffe, despite their great grandfather being Jewish, but it seems that a large number of German generals were of Jewish birth, and the leaders turned a blind eye to this if it suited them. Göring is reputed to have falsified Erhard Milch’s birth record and in response to protests about having a Jew in the Nazi high command, Göring replied “I decide who is a Jew and who is an Aryan”.

After the war, Dietrich returned to civilian life and made a career in German industry and was a sports flyer. He died in 2001, in Munich, only three or four years before I started researching our German family tree on the internet. Was Dietrich pressed into the Luftwaffe instead of his chosen profession and made the best of it by reaching the top as a hero fighting for his country, or was he a ruthless Nazi intent on helping Hitler to achieve the domination he craved? I don’t have the answer to this question, but I would very much like to meet the families of his children and step-children.

|

And so to England

We know a little about my great grandfather, Egon Peltz, son of Magnus and Julie, from my grandmother. He must have spent some part of his childhood in Schneeberg, at the family home.

Egon emigrated to Britain around 1895. I think he was involved with the wool trade (hence Yorkshire), and, on his marriage certificate, described his profession as ‘Commercial Clerk’ and his late father’s profession as ‘wool merchant’! But in the 1901 census he describes himself as a Foreign Correspondent.

In 1900 he married Alice Milnes (née Hudson), a widow with two daughters. The following year my grandmother was born. They also had a son, Norman, born in June 1903, who died in March 1911.

Family photographs below show Egon’s family before he left Germany.

I think Kurt and Walter’s sister (Anna-Lucie or only Lucie, we don’t know exactly) is at the front of the photograph on the left with Walter, Amalie, Adalbert and Kurt across the centre and Auguste at the back. The other man, standing at the back, may be Egon – it looks like him, and his hair parting is on the right side. I suppose it is very unlikely that the doll is from Auguste’s factory!

I think that Emilie, Kurt’s wife (Else), Adalbert and Auguste are seated across the front of the right hand picture with Anna-Lucie standing next to Walter, then Egon, Kurt and Horst.

|  |

During WWI Egon was interned on the Isle of Man, and died in February 1918. Many Germans living in Britain were interned from the very start of the war. Some, despite having British wives, were deported at the end of the war.

Apparently there was a wild claim that Egon was killed by a falling bullet after guards fired in the air whilst quelling a disturbance, but we believe that he died of natural causes. He was originally interred in a graveyard on the Isle of Man, but in 1962 the remains were removed and re-interred at the German War Cemetery, Cannock Chase.

|  |

| Egon’s gravestone, Isle of Man | Egon’s gravestone, Cannock Chase |

It is incredible how much information is lost or hidden as generations pass. My father and grandmother had no idea of their Jewish ancestry or of the doll factory in Saxony, and, although we knew that Dietrich Peltz was in the Luftwaffe, it appears that his mother conveniently ‘forgot’ to tell my grandmother (his first cousin) that he was anything more than a pilot.

My grandmother’s father was born in Schneeberg and was aged about 9 when the doll factory was sold, so it seems surprising that my grandmother did not know about it. Maybe the bankruptcy was ‘not talked about’ and we have to remember that her father was interned to the Isle of Man when she was only just aged 13 and he did not survive to return home.

Quite by coincidence, when I received a reply from the Deutsche Dienststelle (the German Ministry for those fallen in war), with military details of Wolfram and Dietrich, the address of the Deutsche Dienststelle is Eichborndamm, Berlin (named after their great grandfather) !

Thanks

I am indebted to Katja Schnürer and her mother for all their hard work researching the Schneeberg archives and German documents online, and to my ancestors for living such colourful lives, and (being wealthy enough to have them recorded!). Without the Family Tree Forum, I would not have made contact with Katja.

My grandmother’s letters, notes and photographs have been invaluable and I encourage everyone to ask elderly relatives to document what they know of their family history.

Also to the many internet entries (in English, German and Polish) which have enabled this research over the past year.

I should warn the reader of the likely (in)accuracy of my translations from German and Polish text, from uncorroborated text on the internet. I have tried to use multiple sources, but inevitably stories become coloured, biased and muddled over time. Having said that, the general content of this research should provide a reasonable account of my German family tree.

Chr1s

© Chr1s 2010

The von Eichborns of Breslau (Wroclaw)

My grandmother spoke of Ludwig and his daughter, Julie, as von Eichborn, but none of the references I have found include the ‘von’.

There is a von Eichborn family, who founded and owned a bank – “Eichborn & Co” – from 1728 to 1956. Two strands of the Eichborn family were ennobled with the ‘von’ prefix to their name – one in 1848, but that family died out with no children, and one in 1908, the banking family from Breslau (now Wroclaw). The banking family had, for some generations, the hyphenated surname Moritz-Eichborn.

For several reasons, I was initially confident that our Ludwig was connected to this family:

- he was wealthy,

- he was a banker,

- he had Polish connections,

- his first son was named Eugen Moritz Oswald Eichborn,

- in the 1890s, another of his sons is listed as qualifying as a medical doctor at the University of Zurich, as (Cäsar) Conrad (Curt) von Eichborn, mother Fr. Joh. V. E’ (Frau Johanne von Eichborn),

- he was described as Ludwig von Eichborn to my grandmother, by his daughter, my great x3 grandmother,

- and the name Ludwig is repeated through generations of the banking family, with Hermann Ludwig Eichborn, a musician, lawyer and composer, alive at around the same time as our Ludwig.

However, the von Eichborn family do not have our Ludwig on their family tree and do not think that he was related (unless a long way back). Our recent discovery that my great x5 grandfather was a Jew, with no hereditary surname suggests that, when they had to take a surname, they chose, or were given, the name Eichborn. This appears to rule out any family connection with the von Eichborns.

The use of von, at least by Dr. Conrad von Eichborn, suggests to me that either our Eichborns were pretending to be related to the banking Eichborns (of Breslau), or a third branch of Eichborns was ennobled, or Ludwig’s purchase of land in Zakopane gave him a title (baron?) and the family decided it was equivalent to a ‘von’ ! Some of the references to Ludwig, found on the internet in Polish, refer to him as ‘baron’, and in 1887 there is an entry for a Baron Eichborn in the Berlin address book.

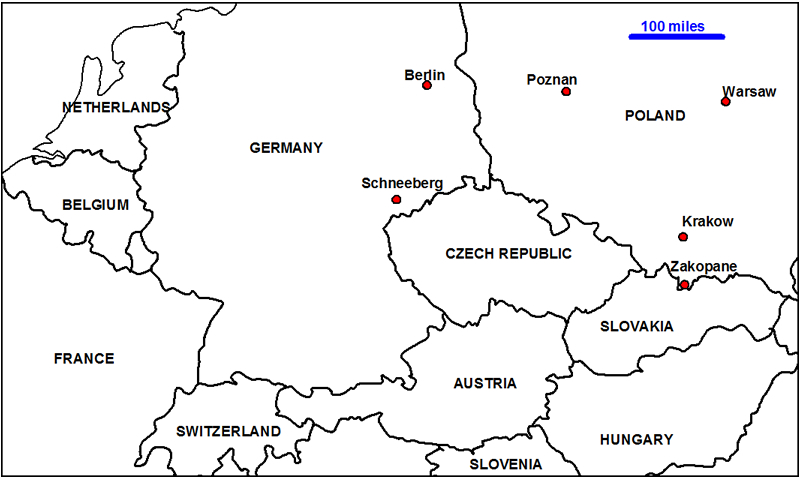

Map showing Poznań, Schneeberg, Berlin and Zakopane, with modern day borders

The following map shows the towns and cities of Schneeberg, Berlin, Poznań and Zakopane with modern-day borders. Clearly the journeys between Berlin and Schneeberg and between Berlin and Zakopane would have been long and difficult – bearing in mind that Zakopane did not even have street lighting at this time, and there was no rail service to Zakopane until 1899. Running a large business in Schneeberg and another business in Zakopane could not have been easy.

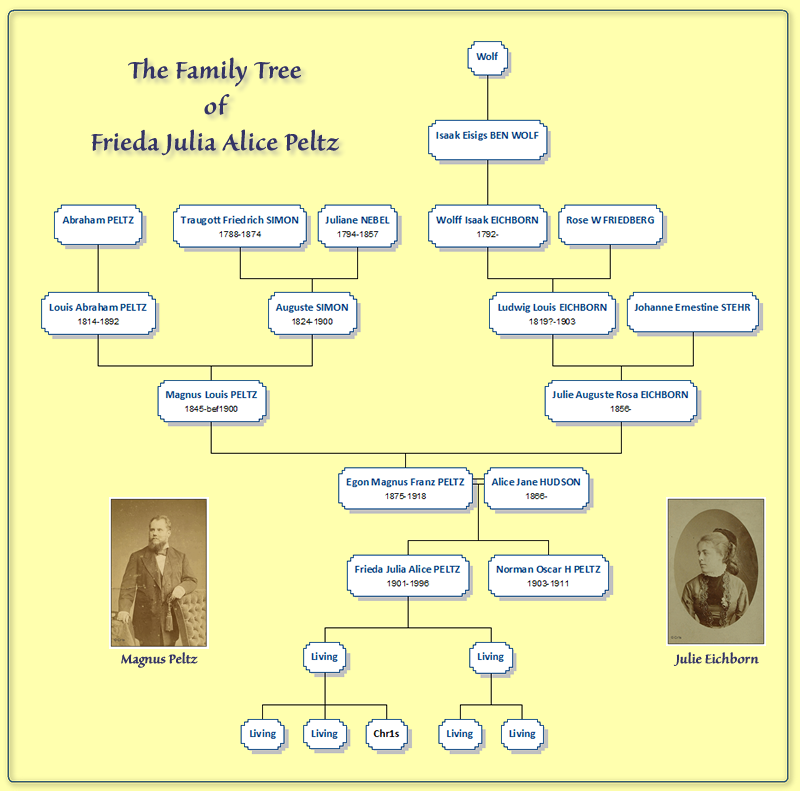

The Ancestors of Frieda Julia Alice Peltz

The Complete Family Tree