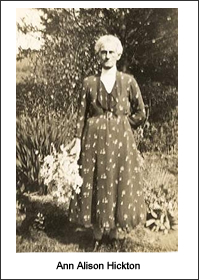

My favourite ancestor and the one I would most like to meet, is my great great grandmother Ann Alison Corbett. From the information I have been able to find, her life was at least interesting and quite possibly exciting, but she also faced more than her share of dangers

Ann Alison Corbett was born in the Gorbals, Glasgow, Scotland on the 28th of November 1826. She was the second child of James Corbett and Jean Ellis. James was a cabinet maker/joiner by trade and was probably involved in the making and repairing of cotton looms. Some of his forebears seem to have been cotton weavers or cotton merchants.

Some time between Ann’s birth in 1826, and 1829, the family moved to Belfast in Ireland where Ann’s three brothers were born. The family seem to have remained in Ireland while Ann was growing up. In 1848, at the age of 22, Ann married Henry Thomas Hickton a soldier in the 1st Royal Regiment, who was stationed at Mullingar, Ireland. Ann and Henry had two daughters while they were in Ireland; Jean in 1849, named after Ann’s mother, and Caroline in 1851, after Henry’s mother. Jean died in infancy and was buried in Ireland. By 1853 the Hickton family were living at the barracks at Fort George, near Inverness in Scotland where their son James, named after Ann’s father, was born. James was my great grandfather. By this time Henry was a private in the 34th Cumberland Regiment. He was with his regiment when it sailed for the Crimean Peninsular in 1854.

In order to find as much as I could about Henry and his life, I contacted the 34th Cumberland Regimental museum and the curator very kindly sent me a photocopy of part of the regimental history relevant to the regiment’s time in Crimea. I will quote from sections of it here.

With the outbreak of the Crimean war the 34th Regiment left Sheffield for Portsmouth on the 22nd of August 1854 where it embarked for the Mediterranean and landed at Corfu on the 8th of September. It remained at Corfu for a couple of months before being ordered to the Crimea. Soon after the regiment had arrived back from the West Indies it had been depleted of its best men by giving volunteers to other corps going to Turkey, so that by this time it consisted mainly of young soldiers, and when it proceeded to Crimea nearly two hundred of its men were left behind at Corfu, being judged unfit for the present for the hardships of the Crimean winter.

The Regiment of twenty-one officers, thirty-five sergeants, eleven drummers and five hundred and fifty-four rank and file, under the command of Major Goodenough, embarked on the 22nd November and landed at Balaklava on the 9th of December. On arrival at the front, they joined the 1st brigade of the light division, and at once took up their share of trench and other duties.

As was usual for that time, a number of the soldiers’ wives sailed with the regiment. The allotted number was six wives per hundred men and the selection was by ballot. The wives who accompanied the troops were ‘on the strength’ of the regiment and could therefore draw rations. There were no provisions made for those who were unsuccessful and they faced destitution and were reliant on their parish of birth to provide for them until the troops returned.

The birth of Henry and Ann’s fourth child Ann, aboard the ship Dunbar off the coast of Corfu in 1855 provided clear evidence that Ann was also at the Crimea at some stage and this fitted with a family story that she ‘nursed with Florence Nightingale, helped the women and delivered babies’. As there are no official records of the wives who travelled ‘on the strength’ it is not known if she was selected to travel with the regiment or if she travelled there at a later date on her own as some wives clearly did.

I was keen to find out more about the wives of soldiers who accompanied their husbands to war. Because there are no official records of who actually went or what happened to them, it is only possible to surmise what life may have been like for Ann. Some information suggested that women with children were automatically excluded from going, but other sources seemed to report the numbers of women and children sailing with the troops. Ann had two young children, they may have accompanied her, or she may have left them with her parents, who by this stage were living in Burnley, near Manchester. On her return from the Crimea there is certainly evidence that Ann and her children were living in Burnley.

In the absence of official records about the Crimean women, I was referred to a book; ‘Colonel’s Lady and Camp-Follower’, by Piers Compton. The information in the book comes from the letters and diaries of officers wives, and a number of other women who visited the scene of battle as sightseers.

From the descriptions in this book it is possible to get some idea of what life must have been like for the wives of the common soldiers.

While there was no provision made for the wives who were left behind, it appears that there were not many made for those who went either. There were no tents for the women, some may have been lucky enough to share a tent with their husband and a number of other men, but many resorted to sleeping in ditches with only a blanket for covering.

Not all wives accompanied the men to the battlefields, some remained at the barracks in Scutari where conditions were squalid and there was little to occupy them apart from the gin bottle. While the living conditions were very harsh for the women in the early stages of the war, once people in England got the news of what was happening, charity workers and supplies arrived especially for the women. Florence Nightingale set up hospitals for the men in Scutari and others set up hospitals for their wives. If the family story is to be believed, then it is likely that Ann remained in barracks in Scutari rather than accompanying Henry to the battlefield. There may be some truth in the stories as she practised as a midwife later in her life, however there were very few wives of common soldiers who were thought suitable to help Florence Nightingale and her nurses.

At some time in 1855, Ann left the Crimea to return to England on the ship Dunbar, where her daughter Ann was born. No record has been found which gives the date for this birth, but later records for Ann confirm the place of her birth.

Henry remained in Crimea with his regiment.

In June it was determined to effect the capture of the Mamelon and the Quarries in front of the Redan, and preparatory to this, the third bombardment was commenced on the 6th to reduce the fire of the place. As the guns of the former enfiladed the latter, it had been arranged that the British were not to attack the Quarries until the French had obtained possession of the Mamelon. Following out a well arranged programme, the French attacked shortly before 7pm on the 7th, and as soon as they had established themselves, Lord Raglan gave the signal for the British to advance.

The storming party, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell of the 90th Regiment, consisted of four hundred men taken in equal proportions from the second and light divisions, with the 62nd Regiment, six hundred strong, in support. Both the 34th and 55th were thus among the stormers, and in almost equal numbers, the latter having five officers and one hundred and sixty men, and the former seven officers and one hundred and seventy men engaged in the combat.

Turning like enraged lions at bay, the British charged with such fury that the front ranks of the enemy shook again, yet it was of no use, back they were forced, although it was but slowly; but gathering strength, they hurled themselves a second time on the Russians with such vigour as to send them a second time out of the Quarries; again the enemy forced them back, and for a third time did the infuriated soldiers fling themselves upon the Russians like a surging hurricane, and drove them out in total disorder….

As might be expected, the casualties of the allies during this nights work were very great. Of the 34th, Lieutenant Lawrence and ten men were killed.

One of these ten men was my great great grandfather, Henry Thomas Hickton. News of his death was published in the London Gazette on 22nd June 1855.

The regimental muster rolls indicate that Ann and their three children were living in Burnley at this time.

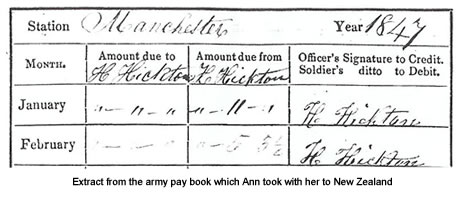

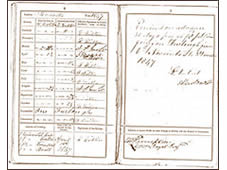

With the death of her husband Ann was left very much alone in England with her children. Her brothers had emigrated to New Zealand over the previous five years and it appears that her parents had left to join them, possibly about the time that Ann returned from Crimea. It may have been the plan that when the war was over Ann and Henry would join them all. Now on her own, on the 18th of April 1856 Ann and her three small children aged 5, 3 and 1, left from Gravesend on the ship Lord Burleigh for Auckland, New Zealand, arriving on the 8th of August 1856. With her she brought reminders of the husband she had lost, his army pay-book and his Crimean medals.

KiwiChris

© KiwiChris 2007