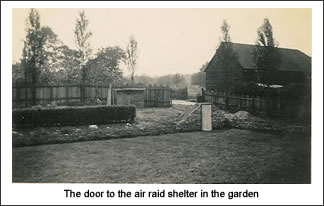

I remember it was a lovely sunny Sunday morning the day war broke out. We listened to Mr Chamberlain’s speech on the wireless in the kitchen, the only wireless we had, and my parents were very serious and shooshed us when we, my two younger sisters and I started to speak, not really understanding what it was all about. My father took us across to the air raid shelter he had made in an old underground farm slurry tank and said that we would have to go into this dark, damp and smelly room if there was an air raid, and then had to explain an air raid. I think we also all tried on our gas masks. I believe a practice siren sounded too, to demonstrate how they would sound but maybe that was another time. Later my father had the alarm for Chartridge on the house but that may have been during the cold war, in the 1950s.

The army requisitioned our house and we went to live in Amersham. My father continued his Agricultural Engineering business; he mended the vehicles and tractors for the local farmers. Petrol was rationed but he was allowed it for travelling to his business and he would drop me off at school on the way, and pick me up again at the end of the day, or else I caught the bus from the Broadway.

We had to take our gasmasks to school every day and occasionally we would have to practise putting them on, and there was brown paper stuck across the windows in case they were broken in an air raid. But really the war did not affect us very much in school, although it must have been worrying for the teachers. Lessons went on just the same. We learned our tables and poems and songs by heart. We had Music and Movement from the wireless and country dancing in the hall, and played rounders in the playground. Once a week in the summer, we walked through the park down to the swimming pool at Waterside. And, oh, it was cold, but most of us learnt to swim and were given certificates to prove it. We had a bottle of milk at play time but there were no school dinners so those of us who could not go home at lunch time took sandwiches. Girls came from most of the villages and Chesham Bois so there were quite a few who had to stay. Food was rationed of course so it must have been difficult sometimes for mothers to provide lunches every day and nobody had a great deal to eat, an apple perhaps if it was the autumn but oranges were available very rarely and only for children and bananas did not come back until after the war.

Later we kept chickens and rabbits and even had three nasty tempered geese for a time. When it was time to eat one of the rabbits my mother would take it to the butcher and bring back what she said was a different one so we did not feel we were eating one we had known. The chickens were kept mainly for their eggs.

When I was in the top class I used to walk to my father’s workshop at lunch time and have soup or sandwiches with him, and walk back to school. It was a long walk at ten years old but we thought nothing of it and I preferred hot soup to eating sandwiches at school. One day my father’s dog followed me back as far as the shop at Berkley Avenue and ran off instead of returning home. But that one had been a stray in the first place. My father always had a dog as a watch dog around the works. It was difficult to feed dogs of course. Dog biscuits or cereals were very scarce and had to be bulked with stale bread and scraps etc. It was said if they did not have meat they would go a bit mad so my father had an arrangement to feed his on horse meat. I remember going with him to the knackers’ yard in Church Street (I think it was) to collect it once. We had to boil it up before it could be fed to the dog, raw meat was also said to be bad for them, and it smelt horrible.

Around 1943, Mrs Phyllis Heron started the First Chesham Rangers. She thought that girls ought to be taught how to cope as the war went on and that this older branch of the Girl Guides could provide the sort of training and experience that would prepare us to live in what ever situation we found ourselves in. She was something quite senior in the organisation, and was from one of the Chesham families, and had access to all sorts of people and places. She arranged proper classes from experts, asking the St John’s for First Aid Training, an army officer for Map reading and Drill, an historian to tell us the history of the town, an architect to explain the oldest buildings in the town. She included cookery classes and took us camping; our first camp was in the garden of her friend Lady Barlow at Wendover. I can still remember the smell of the grass in the tent and the hard ground under my sleeping bag (made from an old eiderdown, we couldn’t buy a new one in wartime) and we had social evenings in the Scout hut in the park to which we could invite friends including boys if we wanted. Rationing being so strict the refreshments were only minimal, but everybody contributed something, with squash to drink but we managed to have fun playing silly games. Later we graduated to the Saturday evening dances at the Laundry. Every year we paraded through the town with the other youth groups, and helped with the Fete that was held in the field at Germains, raising money for all sorts of good c

My father was a Special Constable, a part-time Policeman, during the war, which meant being on duty at various places especially at night in case there was an air raid. He was on duty the night some incendiaries were dropped but Chesham suffered very little damage. We could see the air raids over Slough, the sky was sometimes glowing red and we could hear the noise of the bombs if the wind was right.

When America entered the war American airmen suddenly appeared in the town from where they were stationed at Bovingdon, with their loud voices and different language they were quite unlike our own soldiers who were tired after fighting so long.

On VE Day 8th May 1945, we had a holiday. One of us made up some little buttonholes from flowers from her garden and we wandered round the town, not quite sure what we should do but enjoying the celebratory feel from everyone we met.

VJ day was 15th August 1945 and some of us had gone camping on a farm near Hampden. We decided we would leave our tents carefully tied up and go up to London, to see the celebrations. We had heard of those for VE Day and wanted to be part of it ourselves this time, we were not at all sure Mrs Heron would approve but decided to risk it, cycled from our campsite and caught a train from Missenden. We felt quite daring, we did not go on the train much anyway and some of us had only been to London once before when Mrs Heron had taken us for a weekend as part of the cultural education she felt we needed. We had stayed in Guide headquarters, been taken round the National gallery, seen lots of famous building and then gone to the opera to see Faust. Knowing how to catch the train and how to use a map to find our way around gave us the confidence to go on VJ Day.

It was a really exciting day, we just wandered around gazing at the other people, seeing people dancing in the streets and exchanging jokes and chat with all and sundry. In retrospect it was surprisingly good humoured, and I don’t remember any unpleasantness or excessive drunkenness. We certainly did not drink, not something we would have considered then although we were all around sixteen, and returned to our campsite that night very tired but very happy.

Chesham organised its own victory celebration for November with a torch light procession and a service of thanksgiving. I do not know all the organisations which took part but the scouts, guides, rangers, and church lads brigade were represented. It seems I kept the directions for this. I don’t know who wrote them but they seem to have considered everything:-

Torchlight Procession Friday November 30th

All youth organisations meet at Scout Hall 7.15 prompt. There we shall split up into two parties under two marshals and three sub-marshals. Taking the torches (unlighted) we shall then proceed, party no.1 via Whitehill and party no.2 via Beech Tree to walk to Dungrove. There we shall form one long line across the horizon, with a marshal at the head of each end and sub-marshals a third of the way along each two parties. The torches will be lighted at 7.35 by the marshals and sub-marshals. At 7.40 each party shall proceed back the way they came in single file till they reach White Hill School and the back footpath respectively, where the procession will form into threes, simply walking into position under the three sub-marshals. Both parties then proceed to the park. Party no.1 (White Hill) will turn left at entrance and Party no.2 (Beech Walk) will turn right at entrance, both parties then walking towards one another along the Avenue side of the pond until they reach the Bandstand steps which they will go up together, fanning out at the top round the sides of the bandstand. Then will follow the ten minute service. After the service each party will proceed to line the Avenue for the C.L.B band to Beat the Retreat. Each party of three lines of torches will split into two to line the Avenue. At the finish of Beat the Retreat the C.L.B. band will march to the Church end of the Avenue and, picking up the first torch bearers will march back down the Avenue between the torch bearers, but eventually drawing all torch bearers behind them and going to the Drill Hall. Marching round the quadrangle the torch bearers will then plunge their torches in the water buckets standing there, stand them against the wall and go in twos up into the Drill Hall and obtain their refreshments and continue round the Hall out of the way of others following behind. The evening will conclude with a short social. As it is hoped at least 250 will be taking part, will as many as possible read the above in order to know roughly what is happening.

As you can see it was very carefully planned and I believe it looked quite spectacular as the lighted torches lit up across the hill and then moved down into town. I know those of us taking part felt it was something really special and we were proud to have taken part.

Marjorie Dawn

© Marjorie Dawn 2007