When I started my family history many years ago, I fell into conversation with an elderly man in the records office. When he heard that I was researching the Holdens, he said, “Ah, you’ll be descended from the Manorial Holdens, no doubt”. I smiled and said that I doubted it. We are very ordinary people, nothing manorial about MY family.

But the idea stuck and one day when I had finished my own research early, I decided to have a look at these ‘Manorial Holdens’, just out of interest. That was the beginning of a quest which has obsessed me ever since – to sort out the ‘Manorial Holdens’.

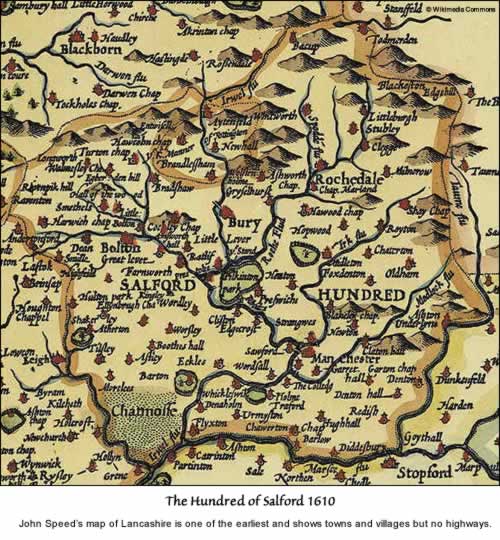

Accepted literature states that the Holdens were an ancient county family, one of the oldest in Lancashire. The earliest important reference is in 1287, when Robert, Richard and Robert de Holden, were granted lands in Duckworth, Oswaldtwistle, Haslingden and Simondstone by Bishop de Lacy, which had been seized from William de Keelim, a traitor. This document and the wording suggest that the Holdens were already manorial – de Holden being the name of the manor, not a family surname (surnames as we know them today were not in general use). However, there were at least two previous generations recorded at this time, Ralph and Robert, taking the family back to the late 1100s. Whitaker, the noted Lancashire historian states that the Holdens were mentioned in the Domesday book. A kind FTF member has sourced a possible reference to land holdings in Cheshire, as Lancashire as a county did not exist at the time of Domesday.

In 1202, Robert de Holden (the elder, I assume) married Lady Cicely de Mitton. Her marriage agreement brings more land to the Holden portfolio, but importantly (as it turned out much later), she also brought Dower lands to the marriage, including a ‘Doffe Coat’ (dove cote). In fact, a dove cote in the context of a dowry was a dwelling house to which an abandoned or disfavoured wife could retire should the need arise.

The family continued to amass land and manors for another 200 years and then, so I was told, there was a gap in the records covering the period of the 1400s. In fact, this turned out to be wrong – the records WERE available but not at Lancashire Record Office.

Holden Manor, as a defined place, did not exist, according to Lancashire historians. The ‘Manor of Holden’ was made up of many small manors and there was no central ancestral seat. Again, my research leads me to doubt this view and I do think that there was an ancestral seat, which has long been forgotten, near to Clitheroe, where many of the remote places have Holden in their names. Holden Gate – which is now nothing but a field – seems likely to be an ancient memory of the entrance to the manor. There is also a hamlet, no more than a dot on the map now, called Holden, just south of Clitheroe.

Again, many experts have stated that the Holdens were of Haslingden. Haslingden had no manor as it was part of the ‘Honour of Clitheroe’, which itself was part of the huge Accrington Manor, owned by the Bishops of Whalley. Undoubtedly there was a important branch of Holdens at Haslingden – but they were, in my opinion, an early cadet branch. Their arms differ from the main Holden arms and one explanation for this is that Thomas Holden of Haslingden appropriated the arms of Piers Gaveston into his own, after Thomas was actively involved in the plot to kill Gaveston. These altered Holden Arms are incorporated into the present day coat of arms of Haslingden Borough Council. The original Holden arms also continue, quartered with the Greenwood family, who were the ultimate heirs and successors to the main Holden family. Both families have the same family crest – a moorcock.

The Holdens of Haslingden were the stewards and wardens of the Royal Forest of Rossendale and the Forest of Boland. In the years up to about the 1500s, the moors were thickly forested and were used by the monarch for hunting stag, wolves, boar and badgers and other wild game. In 1507 Henry VII decreed that the area should be deforested and populated. This was done with such vigorous enthusiasm that one hundred years later there was not a tree left and present day visitors to the area must survey the bleak hillsides and wonder where the name forest came from.

It was a short-sighted move, if it was a financial one. The area is remote, difficult to farm and suffers from extremes of weather. The area was mined for pavement and there is a record of Thomas Holden, Abbot of Whalley, granting mining rights to one Ralph Holden of Holden, a no doubt mutually beneficial arrangement. A few isolated farms struggled to make a subsistence living out of sheep, but the area was never a prosperous one and today is virtually abandoned.

The Holdens were prolific breeders and by the 1500s there were literally thousands of them. However, most slipped out of the records because only the eldest son would inherit the manor and lands. The next son would be in the royal court, often in the navy and the next son would be in the church – one for the land, one for the sea and one for the sky. Younger sons would be given the management of one of the many manors and farms, but would sink down the social scale in only a few generations more, when they would be mere ag labs.

However, tribal memories are long in the country and all through the many Holden Manor papers are references and preferences to a humble-seeming Holden – a farmer being given favourable tenancy of an old Holden property, or a reference to “my kinsman” by the lord of the manor.

The Holdens married well, always into other leading county families and by the 1500s they owned over 30,000 acres of moorland and farmland in Lancashire, plus an unknown number of acres which were concealed in complicated copyhold agreements, always with kinsmen. They owned the manors of Holden (mythical so far and there is no collection of ‘Holden Manor’ papers, but many mentions of Holden Manor), Symondstone, Shuttleworth, Duckworth, Mitton, Dearne, Eccleshill, Readley, Chaigley, and were stewards of a dozen more. An unknown younger son went to Ireland before about 1350 and the Irish Holdens are descended from him. The Irish Holden coat of arms echoes the Haslingden coat of arms, in that it has six eagles. The original Holden arms, granted about 1230, show three moorcocks, which later became five, then seven and then eight. Chaigley Manor became the Holden Roman Catholic branch. This family suffered financial and religious repression and had sunk into abject poverty by the late 1800s, although the Holden line continues in the area. The Chaigley Manor Holdens were custodians of the Chaigley skull – the head of a martyred Holden Priest, which they concealed for nearly three hundred years before finally presenting the skull and other holy relics to the local RC church at Catleach.

In 1533 Gilbert de Holden was lord of the Manor of Holden, although he had politely refused a knighthood during his lifetime. His father was Sir James Holden, although Gilbert recorded a pedigree which stated that his father was Thomas Holden… this must have been an error, as the previous Thomas Holden of Holden died more than 100 years before Gilbert could possibly have been born. Gilbert had five living children at the time of his death – Robert, Adam, Christopher, John and Lettice.

Gilbert tried to disinherit Robert but failed. Robert wanted to marry his cousin, Mary Chorley, grand daughter of the Bishop of Chorley, who was his first cousin. As was customary in those days, he needed a dispensation from the Pope to do so and asked the local priest, Father Arrowsmith, to forward his plea for dispensation. Father Arrowsmith refused on the grounds that Robert’s own parents were first cousins too – Gilbert’s wife, Agnes, was the daughter of the Bishop of Chorley. Robert was furious, turned protestant, married Mary Chorley and later gave evidence against Father Arrowsmith which caused him to be hung. Gilbert then tried to disperse his estate by giving it away, but a later court, sitting after his death, restored the property to the ‘Manor of Holden’.

Robert inherited Holden, after being excommunicated and accused of bigamy – his nephew Thomas was later declared the rightful heir of Holden, but gave up this right in exchange for a large sum of money. Brother Adam went off and founded his own dynasty, and the family was split for ever. Again, not true. Adam built a house called ‘Toad Hall’ and Robert built a house called ‘New Hall’. ‘Toad Hall’ turned out to be vernacular for ‘The Old Hall’, so we have Robert the heir at the ‘New Hall’ and Adam the second son at the ‘Old Hall’, which was actually a new one.

Even more curious is the fact that these two dwellings were joined by a secret underground tunnel which was almost a mile long. Local historians say the tunnel was to facilitate passage between the two houses in the deep snows of winter, but that hardly fits with two warring brothers, one protestant and one catholic. My view is that BOTH brothers were catholic and the passage was there to ease the movement of the priest between the two houses.

Robert’s line continued for a few generations, but much of the wealth was dissipated and wasted. Robert had many illegitimate children, but eventually the legitimate line failed and a later Robert sold Holden Manor in the early 1700s. The same day, he bought the Manor of Aston, which was inherited by his only child, a daughter Mary, who applied to the Crown to change her name to Holden (she was married), and that line continues to this day, although it is disguised in the female line.

Adam’s line also continues to this day, as Holden. This line was more sensible in its dealings and this family were well known and respected stewards of many manors. The line also produced three generations of map makers (all called Andrew Holden), and there are some exquisitely drawn estate maps in the Lancashire Records Office, produced in the 17th and 18th century.

Christopher was cut off with a shilling. He is never heard of again and I suspect, but have not been able to prove, that he lived in Ireland.

Lettice married a cousin, Lawrence Holden, and that line also continues to this day. Of John, there is no official record, but I am working on a theory that he is the John who appears in the Darwen area about this time. His descendants always have a first son who becomes ‘Greave of the Forest of Rossendale’, an ancient post which must surely hark back to the days when the ‘Manorial Holdens’ were the stewards of the forest.

The manorial records of this family are mostly dry and dull land transactions, marriage agreements etc., but nevertheless something of the personalities of these people shines through the official prose. There is the touching reference, in 1262, by a Robert de Holden, which says, “this daye my sonne is borne of the boddy of my wyffe, deo gratias”. Followed by an instruction to the “gose man” to kill 50 fat geese “so alle may rejoyze”. I am also amazed at how often wives get a mention in a property transaction. My previous perception was that wives were mere chattels and had no possessions and no rights. The Holden papers appear to tell a different story.

Another surprising thing was to find that almost without exception, the papers are written in English. This suggests that the Holdens were not affected by the Norman Invasion, used English scribes and had little or no truck with Latin.

Most surprising of all though, was the realisation that memory is VERY long in county families, long past the point when those families have descended into seeming genealogical chaos. Lady Cecily de Mitton, the one with the dove cote in 1202, gets a mention in 1866, when a Holden tenants a farm. The tenancy agreement states that the rent is so much a year, plus, “one red rose and two iron arrows on the feast of St Stephen, to the heirs and successors of the Lady Cecily de Mitton”. That was the exact rent due on the dove cote in 1202.

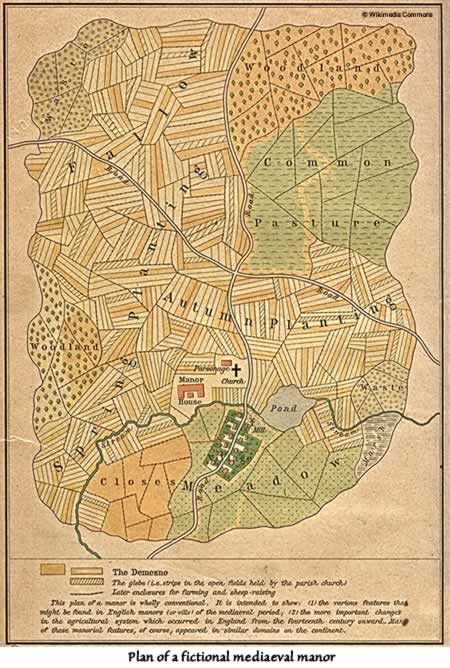

Manorial records may seem daunting and irrelevant at first. However, if you can hook into a manorial family, there lies a fascinating, absorbing and bountiful source of information about the family which can cover 1000 years of history and give you a real sense of ‘where you came from’. A manor was in many respects, a self-governing ‘kingdom’, although the lord was ultimately responsible to the monarch. Manor courts (Courts Baron, Halmote and Leet) dealt with both civil and criminal matters. Courts Leet had juries and a judge (the lord, or steward of the manor) and Courts Leet were not finally abolished until 1977, and some still survive even now with powers limited to property and decisions about manorial matters.

Some manorial records survive almost completely. Others do not. Generally, the larger and more important the manor, the better the survival rate of the papers. However, even patchy, scant papers can provide vital clues to the location of other sources. Almost all property transactions were mirror documents, in other words each party to the agreement had a copy. This realisation has helped me to fill in many blanks – where there is a gap in Holden documents, I turn to the papers of other manorial families in the area.

The criminal cases tried in the Courts Leet have a surprisingly modern tone to them – drunkenness, petty theft, vandalism, assault and nuisance neighbours. There is a sense that these cases were fairly tried and that common sense was applied and that justice was within reach of even the humblest peasant.

You cannot hope to do a classic tree, using manorial records. Rarely, if ever, are birth dates given, but almost always a death date is given and a will filed. Succession by the heir of the manor is always carefully recorded – not necessarily AFTER the death of the lord, sometimes many years before. Pedigrees are carefully recorded by Heralds Visitations. Unfortunately, these pedigrees are self-reported and do not always tell the strict truth, which often emerges in the manorial papers or other family papers.

Land transactions often give three generations of father, son and grandson AND a wife. Field names seem never to have changed in a thousand years of history and the name of a field mentioned in 1199 can be a very good indicator of family continuity if it is mentioned again in 1802.

The more important manors record very formally. The smaller manors often have personal snippets, even recording the weather and crop yields and the death of a much-loved servant.

A good place to start looking is with county records offices of course, but not all manorial papers have been presented at county level. The more important manors will be in the care of the National Archives. Others will be held in private hands, or deposited in libraries and universities. Undoubtedly many more have been destroyed over the centuries, but enough remain to make this a fascinating and informative exercise which may give you a surprising insight into your own ancient family history.

Olde Crone Holden

© Olde Crone Holden 2009

Sources and Further Reading

Whitaker : A history of Lancashire

Lancashire Records Office for:

- The Towneley Papers

- The Shuttleworth Muniments

- The de Mitton family papers

- Chorley Muniments

- Chaigley Manor papers

- Simonstone Manorial documents

- Eccleshill Manorial documents

- Holden manorial/family documents in private hands: various.

- Individual Holden documents

British History Online: Lancashire Manors and Townships

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]