You’ve discovered where your ancestors lived on the census returns, found references to their residence in the parish registers and other records. But where exactly did they live? What were their living conditions like?

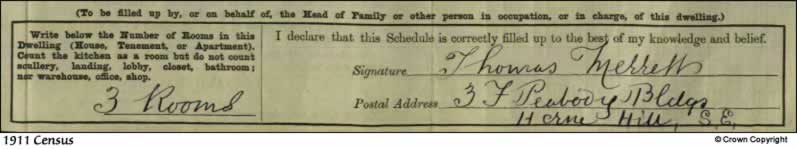

The 1891 census was the first to provide us with clues in column 5 – ‘number of rooms occupied if less than 5’. This was repeated in the 1901 return (column 7), and further elaborated in the 1911, whereby the head of the household had to complete next to their signature and address ‘… the number of rooms in this dwelling (house, tenement or apartment)’. They were advised to count the kitchen as a room but not the scullery, landing, lobby, closet, bathroom, warehouse, office or shop.

With large families commonplace in the 19th century, just how many people were sharing this small living space? In the cities it was usual for families to rent rooms in a large property – just how many people were sharing the same address?

For the humble agricultural labourer, his home would have been a hovel, a basic shelter for him and his family, which was tied to his job and the family would have been homeless if he lost it. Their water would have been from a communal well or a village pump, and the contents of their privy emptied into a cesspit.

The tenant farmer’s cottage may have been more substantial, but still lacked the basic services as we would know today.

The land around them would have been owned by the ‘Lord of the Manor’, under a manorial system dating back to the Norman Conquest. The tenants held a copyhold title to the land and one of the responsibilities of the Manorial Court was to administer this. To read further about Manorial Court Records please see Guinevere’s article from July 2008: Manor Court Records

In early December 1860, Berkshire magistrate, Henry Tucker, wrote to the editor of The Times drawing readers’ attention to the overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions of agricultural workers of the Faringdon Union. He went into great detail describing the living arrangements of various parishioners in the villages of the union. Here is an excerpt:-

Shrivenham – Six cottages, having 35 inmates sleeping in six bedrooms, some of them grown up sons and daughters, only one privy for the whole, and that in a bad state.

Longcot – Man and wife with a child, one widower, and one single woman with a child, making six persons sleeping in one room; two daughters each with illegitimate child, a son aged 20 cohabiting with a woman and four other persons, making ten in one room, with two beds.

Faringdon – Sixteen cottages in Red-row…. In one cottage the drain flows into the sitting- room and in another the drain at front door is offensive.

He finished his letter with a plea to the Government to make provisions to house the poor a priority, rather than advancing “money to landed proprietors for the draining of land, erecting farm buildings &c.”

The 19th century saw great changes to British agriculture, and as more of the work was mechanised, the amount of labour required was greatly reduced, leaving the agricultural workers the choice of either emigrating or moving to the new industralised cities to find work.

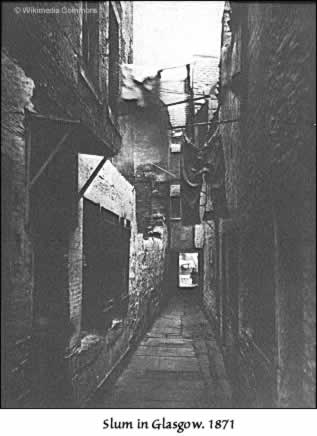

They were soon to discover, however, that these city streets were not paved with gold. There was no social housing as we know today. Instead our ancestors had to rent a room(s) in properties from, often unscrupulous, landlords, and as most could barely afford the very cheapest of rents, they ended up in the slums. These neglected, dilapidated properties were either old houses, whose affluent occupiers had long-since moved to the suburbs, or new, badly built ‘back-to-back’ houses which were hastily and cheaply erected to meet the demand of the huge influx of workers into the cities. Both were subdivided into rooms (including the cellar), where whole families lived in cramped, damp and cold conditions, lacking the most basic of sanitation. It is no surprise that it was a breeding ground for diseases such as typhoid, cholera and dysentery, and that rheumatism, bronchitis and the feared tuberculosis were commonplace. Infant mortality was particularly high.

A cholera outbreak in Blackfriars, London, was reported in The Times newspaper of 3rd July 1849 and paints a rather unsavoury description of the area:

THE CHOLERA IN BLACKFRIARS

Some surprise and alarm has been occasioned by the sudden outbreak of cholera in this locality, particularly near Apothecaries’ Hall. A very slight inspection of the place will render it rather a matter of wonder that it was so long escaped. The four streets called Earl Street, Water Lane, Broadway and St Andrew’s Hill, enclose a space of 180 yards square. In this area there are, exclusive of livery stables, 11 openings, which are again subdivided into varieties of length, breadth and depth, called yards, streets, courts and alleys; these vary from 5 to 15 feet in width and are formed by manufactories, warehouses, shops of all sorts including taverns and gin shops; there is also a graveyard, and, lastly a number of small houses, which are again divided into separate holdings, as many of them contain several families occupying one, two or three rooms – the latter rarely. The drainage of this place is generally bad, and in some places notoriously imperfect, and some of the residents are not very clean in their domiciles. Underneath and around this square runs a very important portion of the sewage of London, and from some of these sewers an addition to the volatile poisons necessarily engendered in such a place is made. In Water Lane alone there are 25 gulley holes opening into a large sewer, about 18 feet below the surface. These are untrapped, and the exhalations from them, at all times unwholesome, are at times intolerable. These holes are disposed in threes, and in one spot there are six with in five yards. Water Lane is about 14 feet in width, but slightly wider at each end, and the houses at either side are so high that the vapours which fill the place have but little chance of being dispersed by the wind. The addition of heat or moisture to various poisonous bases enclosed within this space would at once convert into active gaseous poisons. In this locality 10 fatal cases of cholera and nearly as many attacks have occurred within the last few days.

This was of course the time when Victorians believed that these diseases were caused by ‘bad air’ (otherwise known as ‘miasma’). 1849 was a particularly bad year for cholera outbreaks with tens of thousands of people dying in London alone. However, it wasn’t until further outbreaks in the early 1850s that Dr John Snow found evidence that it was in fact a water-borne disease, caused by drinking water being polluted by sewage.

Change was coming to improve the housing lot for the working classes, but with a country governed by the land owning classes, who only had the sole right to vote, it was slow in coming.

The Nuisances Removal Act of 1846 and the Public Health Act of 1848 were the first to tackle the problem of unsanitary living conditions. The Torrens Act of 1868 gave local authorities the power to tear down properties ‘unfit for human habitation’, with the 1875 Artisans’ and Labourers Dwellings Improvement Act going a step further by giving them the power to clear entire slums. The Public Health Act of the same year encouraged minimum standards of construction, including sanitation, the size of the rooms and even the width of the road outside.

These, together with the Shaftesbury Acts of 1851 – the Labouring Classes’ Lodging Houses Act and Common Houses Act, and the later Housing of the Working Classes Act of 1890, merely enabled local authorities to clear slums, build and regulate properties for the poor to rent. The cost of this was to come from local rates, so you can imagine the reluctance by the local ratepayers to take on this responsibility. Slums were cleared and new properties were built, but not to the extent as demand dictated.

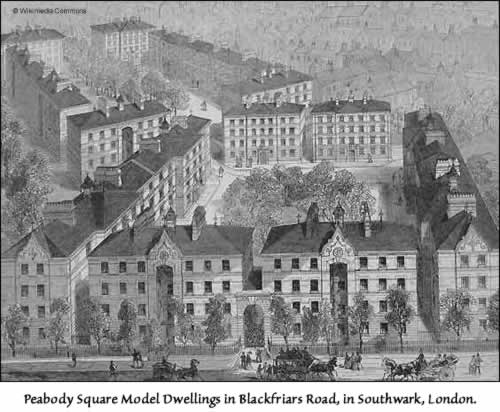

However philanthropists such as London based American banker, George Peabody, were starting to be actively involved in building properties specifically for the working classes. In 1862 he established the Peabody Donation Fund (known today as the Peabody Trust) with £150,000. In February 1864 the first dwellings, in Commercial Street, Whitechapel, were opened for the “artisans and labouring poor of London”. However the rents were still comparatively higher than those in the slums and only skilled workers could afford them.

The Times of 11th January 1866 described the properties built by the Peabody Donation Fund:

Drainage and ventilation have been insured with the utmost possible care; the instant removal of dust and refuse is effected by means of shafts which descend from every corrider to cellars in the basement, whence it is carted away; the passages are all kept clean and lighted with gas without any cost to the tenants; water from cisterns in the roof is distributed by pipes into every tenement, and there are bathes free for all who desire to use them. Launderies, with wringing machines and drying lofts, are at the service of every inmate, who is thus relieved of the inconvenience of damp vapours in his apartment and the subsequent damage to his furniture and bedding.

Every living room or kitchen is abundantly provided with cupboards, shelving and other conveniences, and each fireplace includes a boiler and an oven. But what gratifies the tenants, perhaps more than any other part of the arrangements, are the ample and airey spaces which serve as playgrounds for their children, where they are always under their mother’s eyes, and safe from the risk of passing carriages and laden carts.

By modern day standards the living conditions would have been rather basic, but to our Victorian ancestors, fortunate enough to be able to afford the rent for an apartment in a ‘Peabody Building’, they would have been positively palatial.

Wealthy industralists such as textile manufacturer, Sir Titus Salt and the chocolatiers, George and Richard Cadbury had the foresight to realise that if a worker had a decent place to live then they would be healthier and therefore more productive in their work. They built model villages consisting of houses, churches, schools, bath houses, reading rooms, etc., around their factories, and provided recreational facilities. Workers’ homes had all the modern conveniences, with running water, a gas supply, and plenty of room for the family to live and sleep. Sir Titus created his at Saltaire and the Cadburys at Bournville. Other industralists followed their lead – soap manufacturer, William Lever, of Lever Brothers, built Port Sunlight in the late 1800s, named after his company’s most popular brand of soap

Others too were becoming increasingly concerned about the country’s poor, and between the late 1880s to the beginning of the 20th century, businessman and philanthropist, Charles Booth, undertook a survey of London, mapping every street and colour coding it to indicate the wealth (or more often lack of it) of the residents. These were published as ‘Life and Labour of the People in London’ which is available on the internet using this link: Charles Booth Online Archive. It is a fascinating insight into the world of Victorian London for any family historian. Try searching under the street where you have discovered your ancestors living on a census return – you may even be lucky enough for it to be mentioned in the digitised notes.

It was World War One, which brought about so much social, political and economic change, that saw thousands of troops returning from the trenches to a chronic housing shortage. The Government had intervened during the war, fixing the rents to pre-war prices to stop landlords from profiting from wartime inflation, but now was the opportunity to do so much more.

The Housing and Planning Act of 1919 offered subsidies to local authorities to build new houses for the working classes, which were ‘homes fit for heroes’. The Tudor Walters Report of the previous year set a standard for their design, with fully plumbed, spacious properties, instead of the overcrowded slums.

On the 11th April 1919, King George V and Queen Mary held a reception at Buckingham Palace for nearly 200 representatives of local authorities and societies who were to have the task of supplying the necessary accommodation. The King’s speech was reported in The Times newspaper the following day and in it he said:

The housing problem is not a new problem. It is an old problem which has been aggravated by the past five years of war, and which the forced neglect of those five grim years has rendered so acute as to constitute a grave national danger if it is not promptly and energetically attacked.

His Majesty went on to say that as well as further slum clearance, there was an immediate need for half a million working class houses which, “must be homes”. He asked, “Can we not aim at securing to the working classes in their homes the comfort, leisure, brightness and peace which we usually associate with the word ‘home’?”. He admitted that due to postwar inflation the undertaking would be costly, but saw the return as, “a healthier and more contented people”.

He began concluding his speech by saying that:

Health and housing are indissolubly connected. If this country is to be the country which we desire to see it become, a great offensive must be undertaken against disease and crime, and the first point at which the attack must be delivered is the unhealthy, ugly, overcrowded house in the mean street which we all of us know too well.

If a healthy race is to be reared it can be reared only in healthy homes; if infant mortality is to be reduced and tuberculosis to be stamped out, the first essential is the improvement of housing conditions; if drink and crime are to be successfully combated, decent, sanitary homes must be provided. If ‘unrest’ is to be converted into contentment the provision of good homes may prove one of the most potent agents in that conversion.

However, after such stirring words, and further Acts of Parliament to increase Government subsidies in the 1920s, many were still living in the old Victorian slums. By the early 1930s with the economic depression putting pressure on public expenditure, these subsidies were concentrated on slum clearance and the rehousing of the residents, instead of increasing housing stock in general. The working classes had to look again to the private sector, and during the inter-war years, more properties were built for private purchase, than by the local authority. Mortgages were becoming more accessible for the professional and skilled classes and the level of home ownership rose rapidly.

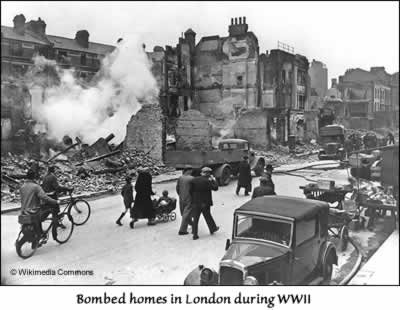

By the outbreak of World War Two over one million ‘council houses’ had been built and half of the designated slums cleared. During the war, Hitler’s bombs destroyed around 400,000 properties and damaged many more, creating another chronic post-war housing shortage, which was further exacerbated by the baby boom. Over the next few decades, public sector housing was built ‘en masse’, and in many cases high-rise.

The Housing Act of 1980 gave public tenants the right to buy at a discount, and The Building Societies Act of 1986 allowed banks to provide mortgages. Both encouraged home ownership, whilst reducing the public sector housing stock

The United Kingdom now enjoys a level of home ownership undreamed of by our ancestors, but the recent economic downtown has clearly demonstrated how fragile that can be. Whilst local authorities and associations provide a housing safety net for the less affluent, it clearly hasn’t produced the utopian society of contented citizens described in the King’s impassioned speech of 1919. The problems of housing the nation have never really gone away, but after discovering where your ancestors actually lived, I doubt if many of you would want to swop places with them.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2009

SOURCES AND FURTHER READING

Victorian London – Liza Picard – ISBN 0753820900

The Home front – Patrick Nuttgens- ISBN 0563207140

Social Housing, An introduction – Stephen Harriott & Lesley Matthews – ISBN 0582285348

Dictionary of Victorian London: Click on ‘Houses and Housing‘

YouTube – Glasgow slum housing

The Victorian House

Victorian Houses on AboutBritain.com

Period House Style: The Victorian House

The Building Trade

Dictionary of Victorian London : Click on ‘Trades and Professions‘, then ‘Building and Construction‘

Old Bricks – history at your feet

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]