At 9:05 a.m. on Thursday December 6, 1917, the world’s largest man-made explosion before the nuclear bomb shook Halifax, Nova Scotia. Through human error, the ‘Imo’, a Norwegian relief ship bound for Belgium, had collided with the ‘Mont Blanc’, a French munitions ship.

Halifax was an important port during WW1, often filled with troop ships and others carrying supplies such as clothes, munitions, horses and pit props (for use in the trenches) and food. Convoys were assembled in the Bedford Basin, in the inner harbour, and on December 6, 1917, the basin was full. Naval escorts remained in the outer harbour. At the time of the accident, nearly 40 ships were waiting to join two convoys which were due to leave within the next few days.

The ‘Mont Blanc’ had arrived from New York carrying a highly toxic mixture – pictric acid (used to make artillery shells), benzol, TNT, guncotton, and live ammunition. Her storage area had been specially modified to prevent friction which might cause fire, having been lined with wooden partitions and fastened with copper nails.

The longshoremen who loaded the cargo had worn cotton socks over their shoes while walking on metal decks to avoid the chance of a spark. She was too slow to join the convoys crossing the Atlantic from New York and had been ordered to join one at Halifax.

The ‘Mont Blanc’ had arrived too late the evening before and had been prevented from entering Halifax harbour by the submarine net which was in place between dusk and dawn.

Similarly, the ‘Imo’, which was on her way to New York to load relief supplies for transportation to Belgium, had been prevented from leaving the harbour the evening before and, as a result, was considerably behind schedule. As she began to zig-zag her way through the vessels in the basin, the pilot noticed a ship proceeding along the ‘wrong side’ (the Halifax side instead of the Dartmouth side) of the basin and instructed the captain to signal by two short blasts on the whistle that she was altering course to accommodate it. A tug with two barges in tow caused the ‘Imo’ to move even further towards the Dartmouth side. The pilot on the ‘Mont Blanc’ hadn’t heard the ‘Imo’s’ signal and gave instructions of his own which meant that that vessel also moved closer to the Dartmouth side.

The Canadian Encyclopaedia states that the pilot of the ‘Mont Blanc’ was astonished to see the ‘Imo’ advancing and the two ships exchanged a ‘bewildering array of contradictory horn and whistle blasts’. The final moments before the collision were filled with panic, both captains ordering their vessels to put their engines in full reverse. This caused the ‘Imo’s’ bow to swing around and her stern struck the ‘Mont Blanc’. The resulting sparks ignited the benzol stored on the deck and the ‘Mont Blanc’s’ crew, knowing the imminent danger, rushed into lifeboats and rowed away as fast as they could. The ‘Mont Blanc’s’ engines had stopped but she continued to drift, eventually reaching Pier 6, where the fire spread to the wharf.

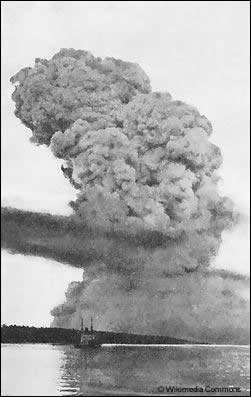

The ensuing fire drew spectators who watched the burning ‘Mont Blanc’ drift across the harbour and who had no idea of the danger. People in homes overlooking the harbour stood at their windows or in their yards watching the fire. In the nearby railyards at Richmond Station a telegraph operator tapped out a last telegraph message advising an incoming train that a munitions ship was on fire in the harbour – he did not survive the explosion but his actions stopped the train and saved passengers’ lives. A dense column of smoke reached heights of 60 metres and twenty minutes after the collision, the ship blew up. The ‘Mont Blanc’ shattered into millions of pieces which rained down on the city as shrapnel.

A city in ruins ~ The Halifax Explosion

Peggy Gregoire ~ An eyewitness account.

Over two square kilometres of the north end of the city were totally obliterated, either by the explosion or the ensuing tidal wave, which surged 18 metres above the high water mark. The roar of the explosion was heard as far away as Cape Breton, 400 kilometres away; it broke windows in Truro, almost 100 kilometres away, and the fireball rose 3600 metres in the air, vapourising all in its path. Photos of the plume of smoke were taken over 40 kilometres away. Naval divers who were under water at the time reported seeing most of the water in the harbour being displaced as the shock wave hit. Two ships which felt the concussion nearly 30 kilometres out at sea immediately changed course to assist in rescue efforts.

Survivors reported feeling an immense pressure on their bodies and many were thrown great distances. ‘A sailor, J.C. Meyers, who was only 30 metres away from the blast, heard someone call “Look out!” It was the last thing that he remembered until he found himself lying on the ground at Fort Needham, over a kilometre away, wearing nothing but his boots.

The crew of the ‘Mont Blanc’, who had all managed to escape from the ship, ended up in a field in Dartmouth, on the far side of the harbour. They were rescued by a naval launch and placed under armed guard in Halifax; all but one of them survived. Because of the public outcry, they remained under police protection until they left the city. The ‘Imo’ was stripped of its superstructure and beached on the far shore; she lost six of her crew, including the captain.Over 1,600 of the 50,000 population were killed and 9,000 were injured. Those watching from their homes were not immune to injury, many were killed and a lot of them had serious eye injuries or were left blind from the glass shards of broken windows. Many bodies were never found. Thousands were made homeless and many children were orphaned. Total damage was estimated at the time at $35 million.

A Relief Committee was quickly organised and surviving buildings were converted into shelters and make-shift hospitals. Rescue efforts were initially hampered by the forced evacuation of the city – there were reports that a fire threatened the main dockyard magazine – and a snow storm which dumped 40 centimetres of snow the next day. The rescuers were also overwhelmed by the sheer devastation and the number of fires still burning. However, the people of Halifax were fortunate in that the town was the base for over 5,000 military personnel, many of them medical, and they were able to assist with disaster relief. Naval personnel conducted house to house searches for survivors and the US ‘Old Colony’ was turned into a hospital. Naval personnel also helped fight the fires in the port as almost half the longshoremen had been killed in the explosion. The City of Boston, Massachusetts immediately sent a train loaded with relief supplies, doctors and nurses and others to assist.

Morgues were overwhelmed and a morgue was set up in a local school. For nearly a month after the incident, people were turning up there every day in the hope of identifying a missing family member.

By Christmas, most of the survivors who could not remain in their own homes had been provided with shelter. Gifts and treats were provided for the children. In the new year, the city slowly recovered and reconstruction began with many skilled labourers from other parts of Canada and New England arriving to help. Over $30 million was donated from around the world to assist in the relief effort and administered by the Halifax Relief Commission.

An official enquiry into the collision found the pilot and captain of the ‘Mont Blanc’ solely responsible because their vessel was in the wrong channel. The judge handing down the decision recommended that they both be relieved of their duties. The owners of both vessels then sued each other but the judge (the same as who had conducted the enquiry) again found the ‘Mont Blanc’ responsible. The decision was appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, which found both ships equally to blame for the accident.

A bell tower memorial was erected in 1920 and Halifax remembers the disaster every year with a memorial service. Also, the clock on the north face of city hall is stopped at 9:05 as an additional memorial. As a continued thank you, Halifax still sends a Christmas tree every year from Nova Scotia to the city of Boston.

jenoco

© jenoco 2010

SOURCES

Canadian Encyclopaedia

“Explosion in Halifax Harbour” by David B. Flemming

The Halifax Explosion: 6th December 1917