When the Second World War started I lived in Plymouth, the city that had been granted ‘neutral zone status’, because it was decided that it was too far to the south west for the German bombers to reach. In 1939 there were no plans to evacuate the children from this city. At the time most people lived in rented accommodation, as the whole of Britain had fewer homeowners then today.

We lived in rented houses in Strand Street, Cecil Street and, by 1940, we were living in North Road. This was a long road near the centre of the city, close to the main railway station carrying the main line from Paddington in London to Plymouth and on to Cornwall via the Brunel Bridge over the River Tamar. This main line was always going to be vulnerable to attack during wartime, due to the mainly naval service personnel who lived in the city and who would be using the line.

The Blitz

In 1941, I attended the Notre Dame Convent Prep School in Wyndham Square, close to the town centre. My memories of the Blitz are very sketchy as I was so young, but I do remember the drone of the bombers coming over the city, the fire that never seemed to diminish, as well as the searchlights that lit the area for miles around, and the sirens that wailed their dreadful noise calling us to the public shelters that existed. The sirens haunted me then and still haunt me today.

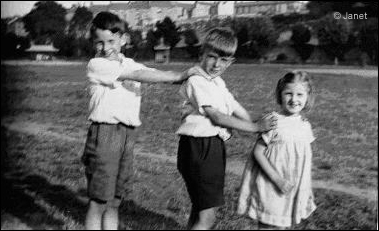

We played in Victoria Park, at the back of where we lived, until the day bombs were dropped, demolishing the bandstand that we played around. The target was the railway line, not the park. There were big craters everywhere and the smell of gas pervaded the whole atmosphere. My two brothers attended St Boniface School, but that school left Plymouth before the major blitz on the city in March and April of 1941. The school evacuated to Buckfastleigh, which left my two brothers aged 7 and 9 without a school. In January 1941 they were sent away to a school in Bodmin and I stayed alone with my mother. My father had already gone back to the navy, rejoining his hospital ship, ‘The Vasna’, and I remember feeling very lonely as my family disappeared from around me.

One day in March 1941, the raids on Plymouth became fiercer, and there were now continuous nights of terror. My mother became distrustful of public shelters after the Portland Square public shelter was blown up, killing hundreds of people. The number of casualties has never been properly counted, as it didn’t include service personnel, and the propaganda of the day was to push the incident into the background, as Churchill was afraid that the whole morale of the country would collapse if the truth was ever told about what really happened in Plymouth during those dark days.

After the war was over, I remember people discussing the event, suggesting that about 500 people had been killed that night in that one shelter. The figure started at about 37 and was over 200 when I last did some research, so one day the whole truth may be told. The public shelter in Victoria Park also became a frightening place to be after the park was bombed many times, and so my mother decided we would shelter under the beds, table or under the stairs, as these places were considered to be the safest in the home. The fires became worse as the whole of the centre of Plymouth was systematically destroyed night after night. People trekked in their thousands to the moors by night, to return for their daytime work. The bombing intensified throughout March and April until the fateful night of 21st April 1941, when Plymouth was ‘coventrated’.

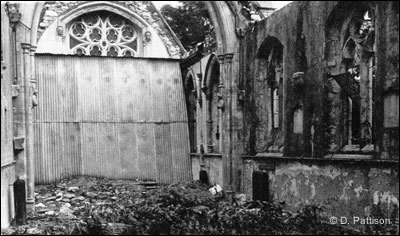

First of all, the house which we had lived at with my grandmother in Strand Street was bombed, although I’m not sure if she was still there at the time. But for whatever reason, she came to live with us in North Road. The house we had lived in at 29 Cecil Street was also bombed, killing two young children called Margaret and Michael Reardon. They were aged 8 and 6, almost the same age as my brothers. The whole family was known to my mother. A bomb skimmed our house in North Road, blowing up two houses behind us, as well as houses beside and in front of us being severely damaged. This was the same night that my school and St Peters Church, both in Wyndham Square, received direct hits, which left them burning fiercely for days. As the school was attacked at night there were no casualties, but the new wing containing the gym, hall and science block, which was only built in 1939, was totally destroyed, along with the nuns’ quarters. By the beginning of May 1941, the Notre Dame School evacuated to Teignmouth, but I was too young to become a boarder.

Evacuation

Reproduced with the kind permission of D. Pattison.

A policy of evacuation of all children was hurriedly put together in May 1941, after most of the city centre schools had either been destroyed or were so badly damaged causing severe disruption. I’m not sure whether my evacuation was private or one which was arranged by the authorities. Whichever it was, I found myself, at almost 5, packing my little brown suitcase to go and live in Bodmin with a family of strangers, the Galbraiths. I remember them well. This was the first of many times of packing that little brown suitcase, which became sometimes a happy and sometimes a very sad symbol of forever moving on, over the next six years.

I attended St. Mary’s School, Bodmin, with my brothers, although only boys were allowed to live in the school boundaries. I have many happy memories of some of the children with whom I attended school and often wonder what happened to them.

I was happy there and remember the Christmas Party of 1941 given for us evacuees, as well as the boisterous home life within this family of five boys, where I seemed to be forever singing the song ‘Run Rabbit, Run Rabbit, Run, Run, Run’. I am sure that as I was the only girl in the house, I was treated differently, which is probably why I remember the experience as a happy one. I only remember my gas mask because I found it difficult to put on, but as I rarely used it, this did not seem to matter very much.

Higher Gillies

In the spring of 1942 my mother came to Bodmin and rented a very lonely cottage called ‘Higher Gillies’ near Lockengate. There was no electricity, no running water and no flush toilet. The cottage was lit by one oil lamp. There was a well outside, from which every drop of water was drawn up in a bucket and this was what we used for cooking, washing and drinking. There were no taps to turn on, no toilets to flush, just a cold dark shed at the end of the garden with a bucket, seat and spiders galore. Lavatory paper was not a luxury to be enjoyed in the war years, and newspaper had to be torn into manageable pieces and pinned to the door, but often this task was forgotten and when there was nothing the discomfort was even worse. Although this was where big dock leaves became very useful! In Plymouth, I had been used to flush toilets, electricity and water from taps and plenty of friends. Suddenly, here I was aged almost 6, living in this lonely cottage. I felt that my whole world had crumbling around me.

The Galbraiths had given me a beautiful blue Persian cat, as well as a book about cats, when I left their family home, but sadly my cat fell down the well and died within weeks of moving to the cottage. At that point I really felt that part of me had died in that well. Living in this cottage meant that we would be a ‘part’ family again. As my father was in the navy, I can only remember seeing him once during the whole of the war. This was in the late summer, early autumn of 1943, when he came home with his sea trunk packed with items of good food to eat, like tinned butter and jam as well as some delicate cream-coloured china cups.

The cottage experience was an event that I hated and will never forget. It was surrounded by fields and some moorland, with no other house in sight. It had low beams inside and meat hooks that were once used for hanging hams. There was a long black range constantly being fed with wood and a wood store we had to keep replenished. On the range stood a big black kettle and a cauldron type saucepan, which was used for stews and boiling the Christmas puddings. Flat irons also stood here and these were heated on the range and used for ironing our clothes. I remember a tin bath which had to be filled with hot and cold water for the washing of us and the clothes. A mangle stood outside to get rid of the excess water from the washed clothes, before hanging them out to dry on a high line, pushed up even higher with a stick to allow the wind to freshen the washing.

There was a small scullery with lattice windows, where my mother prepared the food and we had some strange things to eat like junkets. She would make jams and jellies from the blackberries, loganberries, strawberries, raspberries, wild wortleberries (or blueberries as we now call them), as well as other fruits, which we picked from some woods near Bodmin. She pressed the fruit through a muslin bag tied around four legs of a chair and strained it into a receptacle. Much of the fruit grew wild, but we also had a big garden to grow our own fruit and vegetables. We had plenty to eat in the country. There were rabbits to be snared, although they then had to skinned before cooking. A task which put me off eating rabbit as an adult. About a mile away were a couple of farms and smallholdings, to which I was expected to walk on my own, aged six, to collect eggs, milk and the occasional chicken. We even kept a goat for milk. Toast was done with a long toasting fork held up to the fire until brown on each side.

nr Lockengate, Cornwall in late Spring 1942.

One oil lamp lit up the long hours of darkness and a candle would light me to my bedroom, but this was when the full darkness hit me as the candle brought up the long shadows. When the candle was out, the black went on, and the heavy blackout curtains in the country, without any electricity in the house or street lamps outside, meant that when it was dark, and curtains drawn, everywhere was BLACK and oppressive. When my bedroom door was shut fast against the light, I would lie there rigid with terror, breathing difficultly as panic set in, waiting, always waiting for that shaft of light to come through those heavy curtains. I never could see anything in that jet, black inky silence, and my eyes never grew accustomed to this awesome spectre of black light. I was often found sleepwalking and would lie awake for hours, just thinking. To me it always seemed to be night, and sometimes it was a relief just to sit on the stairs to see some light from the oil lamp, except that my mother was often listening to ghost stories on the wireless that terrified me even more as I scuttled back into bed. To this day I still hate the dark.

However, there were some joyous moments. There was one old man, living in a cottage at the bottom of the road, who showed us many interesting things about country life. He showed us how to make kites with bits of wood and brown paper with newspaper scrunched up for a tail, how to find the right sort of mushrooms for eating, and how to cook them. He showed us blackbirds’ eggs and many other country delights and spoke with a quaint Cornish accent, teaching me many Cornish sayings. My mother was always grumbling about us not coming in for meals, so he taught us how to make whistles out of the Hazel Twig, and we gave one to my mother, so that she could whistle us into tea. Old Mr Thom, as he was called, I remember with much affection. We helped at harvest time to ‘stook’ the sheaves, and hitched rides on the backs of the horse drawn carts, and if we worked hard, there was a clotted cream tea with scones and jam at the end of the day. Weekends and holidays were spent running wild on the moor and climbing trees.

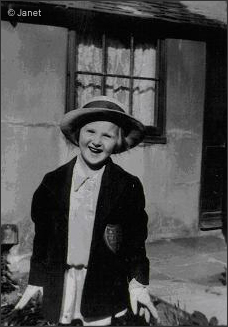

I still went to school in Bodmin on the bus, and after my brothers rejoined the evacuated St. Boniface School in Buckfastleigh, I was travelling, at the age of 6, the four miles each way on my own. The older children on the bus teased me unmercifully, as I was still wearing my convent school uniform, which was oversized, so that I would grow into it one day! With clothes on ration, there was little hope of getting new ones.

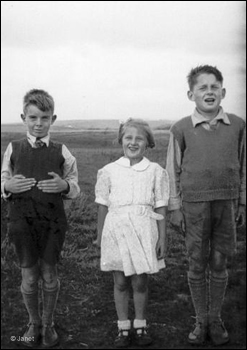

I also remember walking to the Beacon in Bodmin, but friends were few and far between, and the moor, on which we lived, was unforgiving in the winter cold.

Teignmouth

My sister was going to make her appearance into the world within a short while. So one day, just after Easter 1944, I was suddenly old enough, at 7¾, to be travelling by train from Bodmin to Teignmouth, back to the Notre Dame School that I had to leave when they moved there, after being so badly damaged in 1941. My mother travelled with my brothers to Buckfastleigh and then on to Teignmouth, and this was when I remember the troops on the trains and travelling by steam train, and getting drinks from the platform and getting back on again before it departed. At one point my mother had found the train very full with no seats anywhere. She got off the train to see if there were any seats further down, but then the train pulled out of the station leaving her on the platform shouting that her children were on board without anyone looking after us. I cannot remember what happened next, but these were the days when trains often went back to collect people if they had missed them, so maybe that is what happened!

I arrived at the Notre Dame school in Teignmouth and lived at Buckeridge Towers. I was by now a wild child from the country and had a lot to re-learn at my gentile convent school! I rediscovered electric light and kept turning on and off the lights, which wasted electricity. I could use an indoor toilet and could turn taps on. I discovered trees to climb, and was often to be found upside down on one of the branches. There were bamboo trees where we could play games like ‘hide and seek’ and ‘sardines’. I remember the delicious orange juice jam, and the dreadful bread and milk if we were ill!

The whole school at Teignmouth 1944.

I can be found third row from top right on the end, standing with one sock halfway down/up!

We went for walks on the moors and, one day, I led a party of the girls down a track and managed to lose them, only to find a hangar where soldiers were looking at maps. There was barbed wire around the beaches at Teignmouth and I used to sit on the windowsill at night, watching the planes fly over, observing the searchlights. I saw parachutists, but fiction and fact became intertwined. This was a real Enid Blyton existence, and the whole experience for me was fun. I had friends and was taught with older girls, as the school size was so small.

I was continually being chided by the nuns for my unladylike behaviour, but they would sit on the station patiently at Teignmouth, waiting for the train to take me back to Bodmin. The wait was sometimes long, especially during dark winter days. But the holidays brought back other memories, which I tried to forget, as it was back to primitive toilets and washing arrangements, and the loneliness. Sometimes I stayed for holidays at the school, and I admit there was some welcome relief when this happened.

Photograph taken at the Beacon, Bodmin.

Back to Plymouth

Suddenly it was May 1945 and the war was over, at least in Europe. The nuns were returning to Plymouth, to their bombed out school and convent and I was horrified. There would be yet another change for me. What would happen to me now? Back to the cottage? I shuddered at the thought. No, foster parents would look after me in Plymouth and I could still attend the Notre Dame Convent School and have some stability in my life. I would have to pack my little brown suitcase once more and, still, I was not yet 9.

I had a sister by now who was almost a year old. I had seen her a few times, but my mother was trapped in Cornwall, unable to get back to Plymouth. She would have to wait until enough houses could be built to accomodate the thousands of people made homeless by the blitz on Plymouth. Now at 9, it was growing up time, and I returned to Plymouth to live with foster parents in Penny-Come-Quick. But I had lost my friends again. They were older than me and placed in classes above me and this was the hardest cut of all.

These foster parents did not work out for me and I found myself living in North Road once more with new ones. This time, every day, I walked past blitzed houses, where shrapnel could still be found, gaps in the rows of houses where someone once lived, sides torn away, showing fireplaces which once had been lit, wallpaper tattered and torn, decorations still adorning the walls.It used to make me shiver. The city centre had disappeared, collapsing walls and piles of rubble were everywhere. Shopping was from nissan huts and these remained until 1949.

The Notre Dame Convent School buildings remained cramped throughout my school life, because the bombed part was never given permission to rebuild. But this school was my anchor and I have much affection for my old school, as I became interested in sport, guides and sea rangers, which helped me to become the sort of person I am today. It was during these formative years that I became a very young committed European, when I tried to do my bit for uniting Europe, by writing to a German girl in Achen, a French girl in the Loire, and a Dutch boy in Bloemendaal.

I ran even wilder in North Road than in Cornwall, as the bombed sites became my playground and the street lamps were my swings with the ropes we tied from them. Hopscotch was our other amusement, and I soon became extremely independent and streetwise, which has lived with me all my life. From my bedroom window, I watched lamplighters switch on and off the gas lamps each morning and evening, coalmen delivering coal by horse and cart and milkman measuring milk into people’s receptacles. I stayed here until 1947 and hated it as much as the Cornish cottage. I was often in Victoria Park at some fair and was taken to adult films. The daughter of the house was a year older than me and the air was often blue in the morning as we each departed to our very different schools, she to her secondary modern and me to my prep school.

My father was demobbed back to Plymouth and worked at Greenbank Hospital. He tried to live closer to me, as he was concerned about me running wild. The film ‘Hope and Glory’ said it all for me! But he was a stranger to me as I had only seen him once in six years. I took the scholarship from this blitzed experience and somehow managed to pass. Then one day, age 10½, I had had enough of Cornish pasties, Bovril and feeling unwanted. I wanted to go home. The war had been over for nearly two years, but why was I still with these people? I ran away for a day, and when I returned in the late evening, I had been locked out.

A Family Reunited

Soon after this incident in the summer of 1947, we came back together as a family, living in a new council house on the smallest Ham Estate. But what was a family? I was almost 11 years old and had had so many mothers by now. My two brothers were strangers to me, and who was this strange man telling me what to do? I had a sister of nearly three of whom I had seen so little. However the old Manor of Ham was still there, which was my first experience of history, although it is now a library. It soon became my haven, as I tried to settle back into a family life, which had been denied me since the age of four.

The war years robbed me of my childhood, but made me very independent. They gave me my interest in family and local history, as I campaigned against two acts of ‘vandalism’ committed by the local council not long after the war, when the Roundhead stronghold at Widey Court was demolished to make way for the Widey Estate, and the picturesque moorland railway line to Princetown was axed.

I have written many stories about my evacuation during the war for my own children, which will hopefully pass down to our grandchildren. I belong to the Evacuees Reunion Association, where I am still telling the story of these difficult times, where the effects of all wars blight children’s lives everywhere. We are now indeed history, but living history, and I feel that despite our hardships, we can use these experiences positively.

Janet

© Janet 2010

YouTube: Children of the Plymouth Blitz

The Blitz: A Battle of Britain Podcast