What were women and girls from genteel backgrounds supposed to do if they fell on hard times and had to earn a living? Into this category often fell the daughters of lesser clergymen, young widows and daughters of impoverished gentlemen.

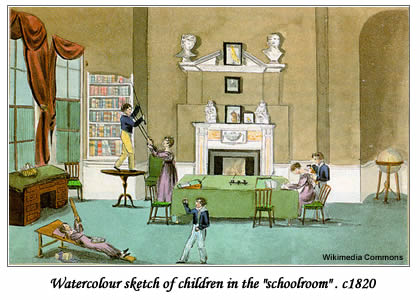

The only occupation that they could consider whilst still retaining their respectability was that of governess. If they were lucky they would have received a fairly good education from their mother and father and could hope to be able to teach young children, in particular girls, in the basics of what was considered at that time an adequate education, reading, writing, music, drawing and French.

A look through the classified advertising section of The Times archive shows that, unfortunately for prospective governesses, supply often outstripped demand. The columns are full of ‘experienced’ ladies, ‘competent to instruct in all the branches of a solid English education’ and capable of supplying ‘satisfactory references’ looking for respectable families.

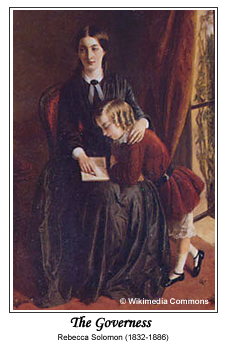

A governess would be chosen as much for her deportment and speaking voice as for her academic abilities. She was supposed to mould her young charges into respectable members of society and for this her moral character was of utmost importance. As a resident governess she would be expected to give lessons in the morning and to take her young charges on a walk in the afternoon. In smaller households she might also have to take on the mending and needlework. Her meals would be taken with the children, but her company might be required in the drawing room with the rest of the family in the evening. In general she would have her own room to escape to at the end of the day.

In taking a place as a resident governess she could hope to find a level of comfort similar to, and sometimes even superior to, that which she had left behind. Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre leaves the starkness of Lowood School for the grandeur and comfort of Thornfield; her room has, “gay blue chintz window curtains, showing papered walls and a carpeted floor, so unlike the bare planks and stained plaster of Lowood”.

“In fact Jane fell on her feet at Thornfield. There was no snooty mistress to constantly remind her of her place, just a nice gentle housekeeper who was very welcoming. The only time she became sensible of her position was during the visit of Blanche Ingram when she had to sit still and listen to that family’s opinion of her profession. You should hear Mamma on the chapter of governesses. Mary and I have had, I should think, a dozen at least in our day; half of them detestable and the rest ridiculous, and all incubi – were they not, Mamma?”

The Brontë sisters knew what they were talking about when they invoked employers’ attitudes to governesses as they had all tried their hands at it. Cassell’s Household Guide c1880 was of the opinion that if a governess conducted herself properly and had a developed consciousness of her own self worth, respect from the family and servants would automatically follow. In reality the governess held a difficult place in the household, balanced as she was, between the family and the servants. The family would look down on her for being poor and obliged to earn her own living, the servants because, despite being a lady, she had to work for money.

To be fair to Cassell’s Household Guide they do have sympathy with the governess and her plight expressing the opinion that:- “There is no class of female labourers whose vocation is generally so little appreciated, and respecting whose position in a family so many differences of opinion exist, as that of the resident governess”.

They even go so far as to suggest that when the employer considers the amount of salary that they are willing to pay their governess, they should take into consideration the periods of time when she will not be needed by the family, but will still need to lodge and feed herself. All too often the salary paid to a resident governess was very low and made saving money extremely difficult. To this end the Governesses’ Benevolent Institution was established in 1843, “for affording temporary assistance to governesses in distress; granting annuities to aged governesses; and to afford a home for governesses during the intervals between their engagements, on their paying a small sum weekly for board and lodging”.

The daily governess could avoid some of the possible disadvantages of the resident governess, but as summed up by this article in Punch in 1843, pay was still a problem:

“WANTED, in Islington, a MORNING DAILY GOVERNESS, of lady-like manners, for three or four young female pupils, capable of imparting a sound English education, with French, music and singing, dancing and drawing, unassisted by Masters. She must be proficient in music and singing, and able to devote three entire morning hours only for five days in each week to her pupils. One resident in the district would be referred, but inferior talent need not apply. SALARY £2 A MONTH! Unexceptionable reference, will certainly be required. Address, pre-paid, to S.S., Mr. Compton’s, grocer, &c., 2, Morgan’s-Place, Liverpool-Road, Islington”.

We can imagine the governess of ‘no inferior talent’ knocking at the door of “S.S.” (Shabby Shabby, of Stony-Heart-Place, is his real address.) How Betty the housemaid, at eight pounds a-year, her board, tea and sugar, pities the elegant drudge as she lets her in! With that gratitude does Betty return to her scrubbing, and dropping upon her knees to her work, how fervently does she thank fate that she cannot impart a sound English education, – that she knows neither French, nor music nor singing, nor dancing nor drawing! She may from the slop-pail look down upon the daily governess, and, from the bottom of her soul, pity her!

Novels of the time often have the governess finding love and leaving the world of the school room behind them forever, Jane Eyre married Mr Rochester, Agnes Grey married Edward Weston, but I wonder if in real life many governesses managed to find their happy ever after?

Georgette

© Georgette 2008

SOURCES

Daily Life in Victorian England – Sally Mitchell

The Victorian House – Judith Flanders

Victorian London

Governesses’ Benevolent Institution

The Victorian Web: An Overview