For the Occupations Section this month we look at the printing industry and its development from woodblock to computers together with a look at its associated trades and occupations. All the illustrations are from “The Penny Magazine”, contributed by Roger in Sussex.

Early history to late 1700s

The woodblock technique, one of the earliest forms of printing on textiles, originated in East Asia and China, with surviving examples dating from before 220 AD. The text, images and patterns were cut as a mirror image into a block of wood, inked, then pressed down onto the surface of the cloth to form the print.

It wasn’t until the 1300s that the technique arrived in Christian Europe and was initially used to print on textiles, producing items such as those used for religious purposes.

However, as paper became more easily available in the 1400s, printing on paper became popular and large numbers of prints began to be produced.

Books which had traditionally been hand written manuscripts, were by the mid 1400s, being produced by the woodblock method and called woodcut books or block books, with text and images carved into the same block.

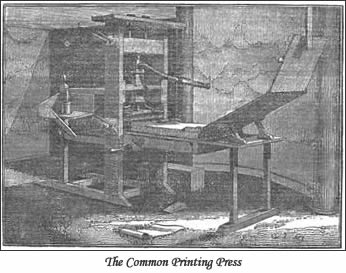

The movable type technique of printing originated in China in around 1040 AD, however, it was the German goldsmith, Johannes Gutenberg, who invented the ‘Gutenberg’ printing press in around 1439, which revolutionised communication and book production leading to the spread of knowledge.

Moveable type is the system of printing and typography using movable pieces of metal type arranged by a compositor, with a piece for each character. Compared to woodblock printing, movable type pagesetting was quicker, more durable, and the lettering more uniform, leading to typography and fonts.

The high quality and relatively low price of the Gutenberg Bible in 1455, established the superiority of movable type, and the use of his printing press rapidly spread across Europe and the rest of the world. Today, practically all movable type printing ultimately derives from Gutenberg’s movable type printing press, and it is seen as one of the most important inventions in history.

Gutenberg was the first to make his type from an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, known as ‘type metal’, ‘printer’s lead’, or ‘printer’s metal’. It was critical for producing durable type that produced high-quality printed books, and proved to be more suitable for printing than the clay, wooden or bronze types originally used in China.

He also introduced the use of oil-based ink, more durable than previously used water-based ones, and published the first coloured prints.

William Caxton, an English merchant, travelled to Europe in the course of his business in the mid to late 1400s, and it was in Germany that he first observed Gutenberg’s printing press. He first set up a press in Bruges, producing the first book in English in 1473. Three years later he brought the new technology to England, setting up his first printing press in Westminster, London, in 1476.

Caxton produced chivalric romances, classical authored works and English and Roman histories, which were poplar amongst the upper classes and nobility. He translated a large amount of works into English, a language which at the time was littered with many different styles and dialects. Through his work he is credited with standardising the English language.

However, as the printed page was becoming more widely available to the population there was unease amongst Caxton’s critics, who were concerned that the poor would become aware and enlightened as to their circumstances and thus become dissatisfied and aggrieved, leading to civil unrest. Caxton ignored these concerns and only saw the benefit of this new technology for the greater good.

It was William Caxton’s apprentice, Wynkyn de Worde, who set up the first printing shop in Fleet Street in around 1500. Around the same time Richard Pynson set up as a publisher and printer nearby. More printers and publishers followed, mainly supplying the legal trade in the area. In March 1702, the world’s first daily newspaper, The Daily Courant, was published in Fleet Street from premises above the White Hart Inn. The area remained the centre of newspaper production until the 1980s, when they moved out to Wapping and Canary Wharf.

St Bride’s Church just off the eastern end of Fleet Street, remains the London church most associated with printing, and the nearby St Bride Library specialises in the type and print industry.

At the beginning of the 17th century the right to print was strictly controlled in England, so the first newspaper in English was, in fact, printed in Amsterdam around 1620. As the century progressed there were many kinds of publication which related both news and rumours. Amongst these were pamphlets, posters and ballads. Even when the news periodicals emerged, many of these coexisted with them.

The English Civil War escalated the demand for news, with news pamphlets reporting the war, supporting one side or the other. More publications followed the Restoration, including the Oxford Gazette and London Gazette, which were both first published in 1665.

By 1720 there were twelve London newspapers and twenty-four in the provinces.

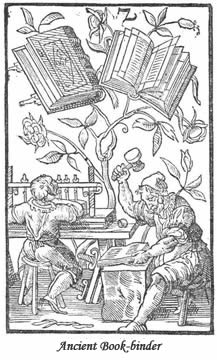

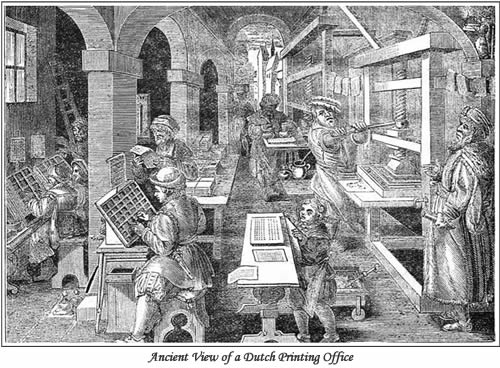

The early printing houses from the 1400s were run by ‘master printers’, who owned the printing shops, selected and edited manuscripts, determined the sizes of print runs, sold the works they produced, raised capital and organised distribution.

The printer’s apprentice was usually between 15 and 20 years of age and was not required to be literate, as the majority of the population could not read or write. They prepared ink, dampened sheets of paper, and assisted at the press. An apprentice who wanted to work as a compositor had to learn Latin and spend time under the supervision of a master.

The printer’s apprentice was more commonly known as a ‘printer’s devil’, because his hands would often be stained with printer’s ink, and, with black being associated with the devil, they therefore gained the name.

Journeyman printers were those who had completed their apprenticeship and were free to move to other employers.

The ‘pressman’ operated the printing press by hand, a job which was physically labour intensive.

Publishing trade organisations, such as the Stationers’ Company allowed publishers to collectively organise business concerns, self-regulate and deal with with labour unrest, as well as implementing copyright.

Late 1700s to present

New printing processes were also being developed.

In around 1796, Czech born actor and playwright, Alois Senefelder, developed lithography. His process involved putting an oil based image onto a smooth piece of limestone and then applying a water soluable solution of gum arabic. During printing water adhered to the gum arabic surfaces and avoided the oily parts, while the oily ink transferred to the paper and from the stone. The word ‘lithos’ is the ancient Greek name for stone.

By the time of the Industrial Revolution the conventional design of Gutenberg’s printing press, which had remained largely unchanged for over 300 years, was being re-examined to improve and increase productivity

Senefelder began experimenting with multicolour lithography in the early 1800s, however it was the new process of chromolithography, invented by Frenchman, Godefroy Engelmann, in 1837, which developed the technique using a separate stone for each colour.

The process of lithography was particularly popular for reproducing topographical prints, maps, as well as the work of artists such as Goya and Daumier

However, it was the printing press (or ‘letter press’) which continued to be the chosen method of reproducing text for the rest the 19th and well into the 20th century.

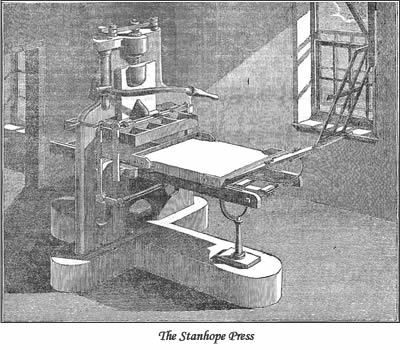

Around 1800, Earl Stanhope constructed his cast iron ‘Stanhope Press’ which, unlike the traditional wooden press, was capable of exerting greater pressure through a system of compound levers. He also doubled the size of the printing area, increasing efficiency and productivity. The ‘Stanhope Press’ was soon used for the production of books and newspapers, including The Times. Many other designs of iron presses followed, replacing the work of the traditional more labour intensive wooden presses.

It was the newspaper industry of the 19th century which led the need for the improvement and development of printing machinery to keep up with their increasing circulation.

The German printer, Friedrich Koenig, was the first to design a steam-powered printing press, whilst living in London in around 1804. He further developed the idea, by introducing a cylindrical press on a rolling bed. Again, it was The Times which was the first newspaper to make use of this new technology, with the first edition to be printed using the new equipment on 29th November 1814.

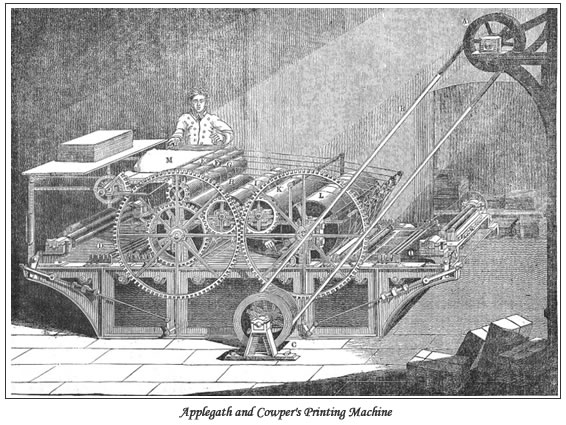

After Koenig returned to Germany, Edward Cowper and Augustus Applegarth, who were employed at The Times as engineers, made further improvement and modifications to Koenig’s equipment.

The Applegarth & Cowper ‘perfecting cyclinder machine’ from 1818 is shown below. Note the hand of the ‘taking-off boy’ in the wheel on the right hand side.

As the years went by they continued to adapt the technology, creating larger and larger presses, which required several people to operate them, further increasing productivity.

By the 1860s, however, Applegarth & Cowper’s presses were being replaced at The Times, by the American Hoe, 10 feeder, horizontal rotary printing machine. Further developments followed allowing both sides of the paper to be printed simultaneously, as well as allowing the paper to be fed automatically into the press by reels, instead of by hand.

By the 1870s all the main national newspapers had installed these, with the provincial newspapers following. By 1895 the machinery was capable of printing and folding 24,000 copies of a complete newspaper in one hour.

Whilst the newspaper printing houses were leading the technological advance of the industry, the small scale jobbing printer was also receiving the benefits of this new technology. Smaller versions of Koenig’s cylinder letter presses were being developed, as well as small self-inking treadle presses.

At the same time the lithographic printing process was also being developed, with the use of cylinders, and began to compete with the letterpress for the printing of text, especially after the development of offset printing, by Robert Barclay, of London printers Barclay & Fry in the 1870s.

Further developments followed, so by the 1960s, printing equipment had evolved from both the letterpress and lithographic processes.

However, back in the 19th century printers offered three types of printing – letterpress, lithography or copper plate printing. Small printers specialised in one process and other large establishments offered all three. They also started to specialise in the type of work undertaken such as newspapers, packaging, books, posters, leaflets, catalogues, legal and business documents etc.

The printing industry was traditionally made up of smaller units working from a private house, with expansion only possible by buying adjacent properties to create a mishmash of buildings. Working conditions were poor and unsanitary, and pulmonary diseases were common amongst workers. The storing of large amounts of paper, ink and turpentine, coupled with the use of candles for lighting made print shop fires common place. As the 19th century wore on larger, more organised printing houses began to be established employing several hundred men.

A printer’s apprenticeship lasted 7 years after which they become a journeyman printer, although work depended on demand and regular employment was hard to find.

The predecessors of the printing unions were the ‘chapels’, with each printing house having their own, to air grievances, enforce discipline and settle wage disputes.

By the time of the Second World War printing presses had improved substantially in efficiency, yet more developments were still to come.

The electronic and computer ages brought more technological advances to the printing industry. Whilst the invention of the photocopier and laser, thermal and dot matrix printers in the 1960s and 1970s provided a means of reproducing copies on a small scale, the use of computers totally revolutionised the whole process, leading to digital printing and desktop publishing.

Just what Johannes Gutenberg would think of our very own FTF Magazine can only be imagined!

Typesetting & The Compositor

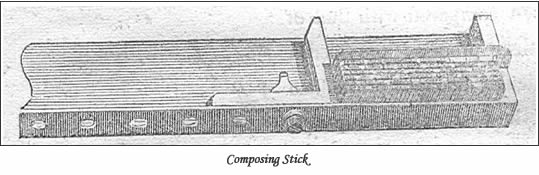

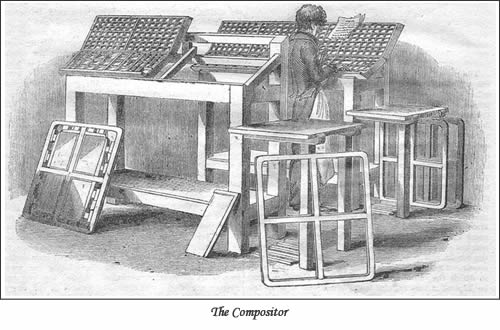

During the era of the letterpress, moveable type for each page of a publication was assembled by hand by a compositor.

Each letter was a cast metal block (or ‘sort’) and these were composited into words and lines of text using a compositing stick, and tightly bound together to make a page (or ‘forme’). The forme was then inked and mounted into the press, and an impression made onto the paper.

Due to the intricate nature of the work, errors were commonplace, so the first impression was the proof, hence the term proofreading.

The sorts were stored in a case with capital letters stored in the upper part and smaller letters in the lower part, from which the terms upper and lower case derive.

Hand compositing was rendered obsolete by the late 1800s, by continuous casting or hot-metal typesetting machines such the ‘Linotype’ which was invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler and enabled one machine operator to do the work of ten hand compositors.

The type was traditionally made in a foundry by hand with a mould and a ladle of molten metal. One man could produce 400-500 pieces of type in an hour. The process was laborious and mechanical methods were developed to increase productivity, but the foundry workers were opposed to them as they threatened their livelihoods.

It was the demands of the newspaper publishers leading the development of the printing industry which forced the need for the mechanised production of type.

However, it was the work of the jobbing printer which required different styles and sizes of type for advertising posters, letterheads etc. Foundries produced sample books to illustrate the available type.

The Victorians were particularly fond of elaborate, decorative type, but by the turn of the century, the plainer Roman type was preferred. Different types continued to be developed, some of which are still used in the choice of fonts today, when for example, creating a document in Microsoft Word. These include Garamond first used in 1922 and Perpetua in 1927.

The most influential of these styles was Times New Roman, which was first used as the type face for The Times newspaper on 3rd October 1932.

In modern times, we now ‘type’ our chosen text onto the computer screen using a keyboard, selecting the style, colour and size with comparative ease.

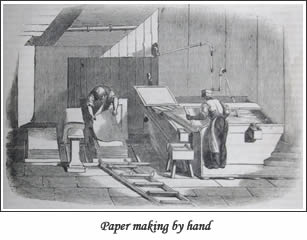

Papermaking

The word paper derives from the Egyptian word ‘papyrus’, a material woven by the Ancient Egyptians from the plant to create a writing material. In around 200 BC, parchment from the split skin of a sheep or goat was developed and it was this that was used for the first hand written books. The making of paper, can trace its roots back to China in the first century.

The use of paper in Europe became increasingly common during the fourteenth century with the advent of the printing press. The traditionally used parchment was expensive and susceptible to humidity, making it unsuitable as a printing medium.

The first paper was made of rags, which were still in use by the mid 1800s, but as demand increased, and so too the cost of the raw material, other sources of fibre were actively sought which resulted in the use of wood pulp.

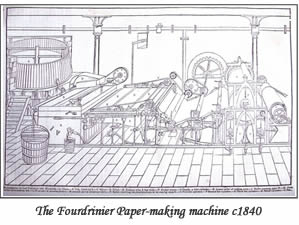

Paper was originally made in sheets by hand, mainly in Kent, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire, to supply the printing shops of London. By the time of the Industrial Revolution, mechanised methods of paper making were being developed to keep up with the ever increasing demands of the printing industry.

Paper making, regardless of scale, involves making a dilute suspension of fibres in water and allowing this suspension to drain through a wire screen so that a mat of randomly interwoven fibres is laid down. Water is removed by pressing and drying the fibres to make paper. A watermark is made by creating a design into the wire screen.

Nicholas Louis Robert of Essonnes, France, developed the first continuous paper making machine, whilst working for the French paper mill, Leger Didot, in around 1799. After quarrelling with his employers over the ownership of his invention, he decided to develop it further in England. However, due to the political situation between England and France at the time, he sent his English brother-in-law, John Gamble. He, through a chain of acquaintances, was introduced to the brothers Henry and Sealy Fourdrinier, stationers of London, who agreed to finance the project.

Gamble was granted a patent for the machine in October 1801 and, with the assistance of the skilled and ingenious mechanic, Bryan Donkin, an improved version was installed in Frogmore, Hertfordshire in 1803.

Further developments followed, with the Fourdrinier brothers installing the new machinery at their own paper mills. However, it wasn’t until the 1830s that these were in general use and the process of paper making became industrialised.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2008

Sources & Further Reading

Printing, 1770-1970: An Illustrated History of Its Development and Uses in England. Michael Twyman. ISBN 978-0712345965

The Modern Records Centre: Printing Workers

Metal Type ~ Stories from the “good old days” of hot metal.

British book trade history This site has collections of indexes of book traders and apprentices.