Peppard Chest Hospital featured large in my childhood as both my parents worked there. Situated in the Chiltern Hills, about six miles north of Reading, Peppard was considered an ideal location for a sanatorium at the turn of the century.

The founder of the sanatorium was Dr. Esther Lillie Colebrook. She had been born in 1871 and was the daughter of a one-time mayor of Reading, George W. Colebrook. Dr. Colebrook had attended the London School of Medicine for Women taking the Licence of the Association of Apothecaries (LSA) in 1896 and obtaining her MD in Brussels in the same year before working in Edinburgh for a while. She was a pioneer in the open air treatment of tuberculosis, which at that time was the most important method of treatment. Dr. C. Theodore Williams lectured in 1898, “the leading principle of the treatment is that the consumptive should pass the greater part of his time in the open air, protected from the weather and, as a rule, in the prone position, and at night he should sleep with the window open”.

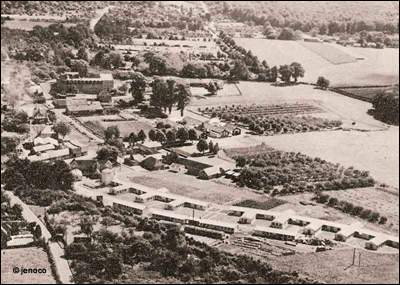

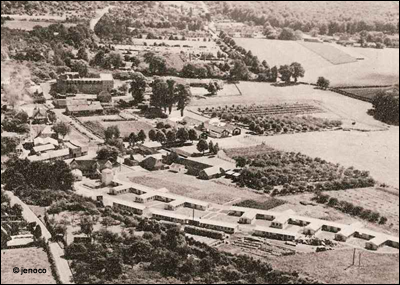

Staff house is the big building towards the top of the picture.

According to Dr. Colebrook, a Reading doctor of her acquaintance knew of her interest and wanted to try the treatment on one of his patients. “A farmhouse near Peppard seemed suitable. Before the days of motorcars, seven miles was too distant for daily supervision but it happened that I, recently qualified as a medical practitioner, was temporarily in residence… and the case was consigned to my care”. The patient was successfully treated and there was considerable local interest, including with two elderly ladies. As it happens, the two ladies later sent Dr. Colebrook a cheque for £2,000 in memory of their brother, Maitland, who had died of tuberculosis twenty years earlier. They later made a contribution of another £2,000. Dr. Colebrook named her sanatorium in Sonning Common, Maitland Cottage Sanatorium, as a result of this contribution.

At the time of the 1901 census, Dr. Colebrook was running her private sanatorium for nine patients afflicted with tuberculosis in nearby Wood Lane, Sonning Common – a nurse, housemaid and cook were the other residents of the house. It must have been quite cramped as the house, which is still there today, is not particularly large.

In 1902, she purchased Kingwood Farm and its 50 acres and had it altered and enlarged for paying guests. She also erected the first building in the country where “patients of small means” could be treated (a chalet she named Maitland Cottage). However, there was no water supply and in years of drought, water had to be transported by cart from the river at Henley.

As the sanatorium grew, lack of a reliable water supply became a problem and a 300 foot well was sunk. Dr. Esther Colebrook had called in her relative and friend, engineer Henry Carling, to advise on the project and in 1904, and, as she put it “a partnership was entered into ‘for better or worse’”, although it was several years before Henry gave up his other work to concentrate on the sanatorium.

The hospital’s reputation grew. One patient was visited by a relative who happened to be the Medical Officer of Health for Woolwich. As a result, Woolwich Borough Council started sending patients to the sanatorium and continued to do so for several years. When Woolwich wanted more beds than were available, the Medical Officer of Health personally lent the sanatorium the money to erect a chalet for three additional patients and when offered repayment at a later date, refused to take the money. The council was pleased with the results, as indicated in an article in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in 1907 – “the educational value of the lessons they (the patients) learned had quickly manifested in the district” and “the cost to Woolwich was a rate of one sixth of a penny”. It was decided to prolong the stay of patients by allowing those who had recovered sufficiently to work within the hospital. Children in particular responded rapidly to the outdoor treatment they received. Although there had been a steady reduction in deaths since 1860, the mortality in England and Wales from tuberculosis in 1907 was over 55,000, or approximately 10% of the deaths.

Reading, Bermondsey and other councils from as far away as Yorkshire also started to send patients for treatment.

Demand for beds was always increasing and the Maitland Trust was established to help with funding. As a result of an appeal, enough money was raised to build a new 20 bed block, making a total of 40 beds. The money for the children’s ward had been raised with the help of a friend of a staff member who, due to an accident, was ensconced at Peppard for several weeks. Miss Stark had previously taught at a school in Switzerland and suggested that the girls of her old school might like to raise the money to enable children to be treated at the sanatorium. In less than three years, £600 was raised and Kindercot ward was built with Miss Stark as its first school teacher, for the children continued their schooling while receiving treatment.

In a letter to the BMJ in June 1911, a Dr. Carling stated that the cost per bed of erecting Maitland Cottage Sanatorium was approximately ₤175 p.a. At that time the sanatorium had sixty patients and included a 40 acre farm, various buildings including a children’s house and several sleeping shelters. It also had a fully equipped laundry. Dr. Carling indicated that she employed ex-patients as staff, “the presence of apparently cured patients is a constant encouragement and stimulus to others”. It also lowered the running costs.

In 1912, the National Health Insurance Act came into force and in 1914, when the sanatorium had grown to 70 beds, Dr. Carling sold it to Berkshire and Buckingham County Councils and it became known as Berks and Bucks Joint Sanatorium. The money from the sale was used by the Maitland Trust to purchase a convalescent cottage at Barton on Sea. It remained under their jurisdiction until the founding of the National Health Service in 1948 when it became known as Peppard Sanatorium.

There were further developments in the treatment of TB around this time – the pneumothorax machine was introduced to the sanatorium and a description of the treatment can be found here: Lung Diseases: Pneumonia

Dr. Ethel Phillips, an English missionary, spent some time at the sanatorium around 1912 and wrote about it in her journal, which was later transcribed into a biography by her adopted son. She described the excellent food and the fact that she enjoyed a glass of rich milk with each meal. She lived in a hut in the garden. She made good progress and part of her treatment included long walks and bike rides. Dr. Carling eventually offered Dr. Phillips the post of Assistant Medical Officer and entrusted the hospital to her care when she had to travel to Italy. Dr. Phillips used the new treatment of pneumothorax injections on herself and attributed this to her eventual recovery.

During WW1, the number of hospital beds grew to 105, with men invalided out of the Army with tuberculosis arriving for treatment. At the end of the war, as part of a scheme to find employment for disabled ex-servicemen, 20 beds were allocated to tuberculous men to be trained in horticulture. In 1919, the hospital was expanded to 180 beds, using buildings from war-time hospitals at Clieveden and Beachborough, as materials were scarce. Over time, these were replaced with more permanent structures.

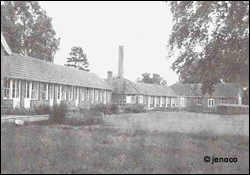

Dr. Carling was a strong advocate for “cleaner and safer milk” as is demonstrated in her letters to the BMJ, and the hospital farm participated in an investigation into milk values. The farm supplied milk, vegetables and fruit and became the centre of the sanatorium with the ‘wards’ growing around it. My friend’s mother worked there in the 1930s and she described how, “the food was cooked in a big kitchen and, in earlier days, transported around the site by a donkey and cart”. There was a hall where the local Peppard rector conducted services on Sundays and various entertainment was held.

Dr. Carling retired in 1938 and on 1st April 1938, Dr. Harley Stevens, an Australian, became the new Medical Superintendent. The hospital grew to 200 beds. Like everyone else, the hospital had to deal with rationing during and immediately after WW2, but the farm proved a big boon as it was able to produce over 80 gallons of milk and 100 eggs per day and fresh fruit and vegetables were also available. After the end of the war, additional beds were added and staff house expanded and a new operating theatre built.

Peter Auliff writes on the BBC WW2 Archive of his childhood stay at Peppard Sanatorium when he was very sick in the early 1940s and of the tough bunch of kids from the East End who bullied others. He remembers seeing “the horizon lit with a huge glow like a great orange setting sun” – the East End of London burning.

In 1948, the hospital school, which had been founded in 1914, was taken over by the Oxfordshire Education Authority. Through the years, many children had benefited from attending school at the hospital, either in person or receiving lessons in bed. The average stay for TB children at this time was three to six months. During WW2, numbers declined and in 1958, 25 children received schooling. The school eventually closed in 1973.

The name changed to Peppard Chest Hospital in 1955. The discovery of antibiotics had brought about a large reduction in the number of tuberculosis cases and in its later years, some beds were occupied by other cases such as geriatrics and paediatrics.

Dr. Carling was a prolific writer and had numerous letters and articles published. She died, aged 86, on March 18th, 1957 in Ipswich, Suffolk.

What I remember about Peppard Hospital.

My father worked there for nearly thirty years and my mother almost as long (she trained to be a nurse at Peppard), so it was an integral part of my childhood. Dad joined the hospital as an under-gardener in 1948 and shortly after that was promoted to head gardener upon the retirement of the previous incumbent. The farm had closed a few years previously but the greenhouses and orchards still provided produce for the hospital’s kitchens and there were extensive gardens to maintain. I can remember four large greenhouses, one of which was dedicated to growing tomatoes, lots of cold frames (can’t remember what was grown in them) and a special building for storing the apples. There was also an annual hospital fete and the main draw was the plant stall so, throughout the year, dad grew pot plants and prepared bedding plants for sale at the fete. Whenever we were visited by my aunts and great aunts (always on a Sunday), they would want to drive or walk up to the hospital (a mile from our house) to look at the greenhouses and admire and learn about the different plants that were being grown.

My memories are of at least six wards spaced out over a very large area – Kingwood, Bowers, West, Summers (named after the original gardener who was with the hospital nearly 50 years), Kindecot, Maitland, and Carling. The canteen and laundry were in separate buildings, as were the administrative offices and there was a water tower. The farm buildings were still intact, although unused, and there were houses on-site for the hospital secretary and some other staff.

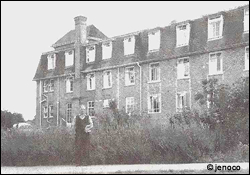

There was a large staff house (my first holiday job was as a domestic there). Male staff were housed on the ground floor and female staff on a higher floor. Sisters had slightly better accommodation at the front of the building, and their own sitting room, and Matron had her own quarters. On evening shift, we used to prepare drinks (not the alcoholic variety) and snacks for 9:00 p.m. and staff used to get together to socialise at this time. Other meals were taken at the staff canteen, some distance away. It must have been unpleasant to have to walk the hundred yards or so to the staff canteen if it was raining and in the winter months, although, at the time, I don’t remember it being a problem – we were just glad to get a break.

Monday nights was film night – I used to go to the hospital hall with my sister and dad to watch the films (not always the most recent!), I think it was every two weeks. The ‘film man’ always started with a cartoon (Woody Woodpecker is one I remember well). It was where I first saw ‘The Wizard of Oz’. There was a little shop outside the hall where we could buy sweets.

Guy Fawkes night always meant fireworks – one year the hospital administrator accidentally set them all off at once – and Christmas meant the children’s Christmas Party with a visit from Father Christmas. Staff seemed to come from all over the Commonwealth. One Indian doctor mistook the pods on the laburnum tree for those she used to eat in her native India and ended up being rushed to hospital in Reading as, unbeknownst to her, they are highly poisonous.

There were also two tennis courts and it’s where I learnt to play, with my father being my teacher.

The hospital closed in 1980 and the majority of the grounds used to build executive houses. However, one of the orchards is still there and the daffodils which my father had planted under the apple trees still bloom every spring.

jenoco

© jenoco 2010

Bibliography:

Peppard Hospital, A Short History (Dr. Esther Carling with later additions by Mr. N. Dove)

British Medical Journal

Henley Standard